The following idea comes from Bruno Masset—it's his idea, not mine. (I just like it.)

He suggests that for high-end inkjet prints (distinguished from the kind of thing that gets spit out on bond paper by four-color dye printers all over the world) that "something technically correct (and therefore defensible) and bland (and therefore without any undesirable connotations)" is needed.

His suggestion is "IHD print," for "Incremental Halftone Deposition."

I looked it up, and "IHD" is also largely available—Microsoft now calls its the Advanced Content interactivity layer in HD DVD "HDi," and apart from that there are only four other entries for the acronym on Wikipedia's disambiguation page, none of them pertaining to imagemaking.

Bruno continues:

Incremental: Microscopically (at the dot level) and macroscopically (at the picture level), the inks are indeed deposited sequentially and incrementally by the print head(s).

Halftone: Just like halftones, inkjet printing is, at a fundamental level, a discrete, non-continuous, dot-based printing system.

Deposition: Self-explanatory.

Bruno adds: "one could also, if necessary, distinguish between 'Organic IHD process' (dye-based inks) and 'Inorganic IHD process' (pigment-based inks)."

• • •

Bruno didn't mention this, but I think that we also need a certification process for specific combinations of materials—a basic suite of test procedures that the community can agree on for determining a reasonable expectation of print life expectancy (LE) and decent handling properties.

I'm on thin ice here, because a number of organizations work in the field of materials testing and conservation and no doubt are much further along in their science and their procedures than I'm even aware of. And I don't have time to do original research into existing published International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards that relate to image permanence and life expectancy and durability. But what I would suggest is a new standard for Paper + Inkset + Printer (P+I+P) combinations that would "approve" a set of P+I+P materials and equipment as being a known quantity that come up to a baseline standard for quality, permanence, and handling properties.

Bruno's naming suggestion would distance premium inkjet prints from the (deserved) perjorative connotations of the worst practices of the medium, and an ISO standard approving specific P+I+P combinations would enable photographers to easily ensure that their choices of P+I+P combinations are acceptable to the collector and exhibition market, and it would create an objective standard so that galleries, museums and collectors didn't have to just take photographers' words that the work they're buying is "archival."

And of course an ISO certification for a paper-inkset-printer combination doesn't in the least limit the freedom of manufacturers or print creators. Manufacturers can make whatever they please and photographers can use whatever they please. This idea would just give a further option for those on the creation side who want assurance that they're working with the best materials, and those on the market side who want assurance that the prints they're trading and collecting were responsibly made and won't self-destruct.

If in the future you were to visit museums and see prints on the wall identified as a "Certified Inorganic IHD Print (2014)," it would be much more useful than just the words "inkjet print" or any of the random replacement desciptions that are now used haphazrdly. Like for instance "archival pigment print.*"

Bruno's original comment appears in its entirely in the Comments to the "Big Mystery" post.

Mike

(Thanks to Bruno)

*Because, really, anybody can slap the word "archival" on anything—especially if there's a financial inducement to do so—and no one can reasonably contradict the claim. Even the word "pigment" is suspect—were the inks pure pigment or simply a dye ink with some pigment added? And how can a dealer or museum reasonably stand by a claim of "archival pigment print" when the terms aren't defined and they're taking the artist's word for it anyway? And anyway nowhere in that casual description is the paper taken into account. It's all very suspect—and that must be hindering the acceptance of premium inkjet prints in the marketplace. When, really, the very best inkjet materials and the very worst inkjet materials are simply worlds apart.

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

TOP's links!

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Jeff: "Wilhelm Imaging Research (WIR) has long made attempts to achieve some degree of standardization…but that's a long topic. Even with such tests, real world print display conditions involve numerous other variables, e.g., lighting, glass, etc.

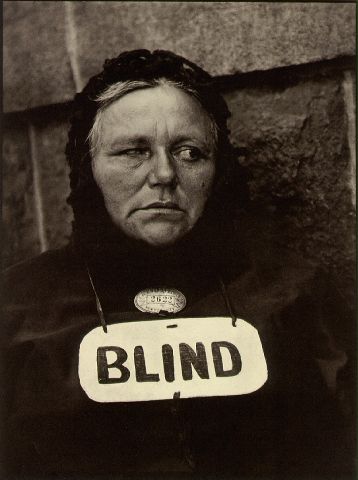

"And beyond that, there are other print techniques that likely help or hinder print longevity, and that's been true long before the advent of digital printing. How, for instance, are Paul Strand's silver prints affected by his sometimes use of varnish spray? Should he have been required to disclose that to print buyers? There are certainly modern day inkjet equivalents involving toning, etc.

"This is not a new issue and, as far as I know, there have never been agreed-upon standards, even for 'silver prints.' Why should this be any different? I think change (real and perceptual) will come based on the market, not based on some required standards. I don't collect vintage silver, or platinum, prints any differently."

Mike replies: You're kind of talking past me here, for which I might be to blame. I'm not talking about a standard for actual LE. I'm talking about a certification procedure for various specific combinations of materials and equipment, so that printing services, photographers, professionals, and other printmakers could easily determine whether their materials and equipment were considered "safe to use" or "acceptable to buyers" or "of known high quality" or whatever words you want to use.

I didn't even mention what the criteria for certification might be.

Thus, Brand E Model X printer might be certified to use with Y inkset but not with other inks; and Brand E Model Y printer with Y inkset might be certified if used with papers A, B, C, D, E, F, N, P, and Q but not with any other papers.

The advantage of this is that when subsequent buyers, exhibitors, and owners want to know if the materials used were of a certain quality, they'd have an objective measure for confirmation of that.

The certification might even use one of a number of actual independent standards as a qualification. For instance, certification might stipulate that the print meet either "Wilhelm Imaging Research Test L" or "Aardenburg Imaging Light Fade Test Z" as part of the criteria.

Get the distinction?

Trecento: "I have only one problem with your proposal: you want an ISO certification. I hate paying ANSI for the privilege of reading supposedly public standards. For instance, ISO 18915, "Methods for the evaluation of the effectiveness of chemical conversion of silver images against oxidation" (i.e. silver print permanence!) costs $114 USD. Erecting a paywall would significantly reduce the effectiveness of your proposal. As an alternative model, I would suggest something similar the different Open Source licensing models, like the LPGL. A nonprofit entity is created to hold the trademark for IHD, and creates a set of standards for how/whether prints can be marked as IHD."

Hugh Crawford: "I'm pretty sure that no one uses halftone screening which is an amplitude modulation technique. Everything I have seen uses stochastic screening.

"I'm not so sure about the incremental part either. Canon printers for instance seem to put down the different inks all at once, i.e., any one color drop of ink can have any of 10 other colors deposited over it.

"Deposition has a nice ring to it however.

"So: Variable Stochastic Deposition print?

"VSD also stands for the Swiss printers trade group, Variable Sized Dots, and Voltage Sensitive Dyes, which might confuse someone, but I wouldn't worry too much. And the Swiss printers trade group is probably too freaked out about inkjet technology in general to care.

"As an aside, I wouldn't want to get the whole organic vs. inorganic and dye vs. pigment terminology baked into the name. The average consumer has no idea what organic means. Gasoline is organic, water isn't. Lake pigments have pretty much the same performance as dyes. Some azo dye (see Cibachrome) is a lot more archival than some nonorganic pigments. Carbon and bone black is about as archival and organic as you can get, yet it gets listed as a non-organic pigment in some listings. Quinacridone seems to be a leading high-performance archival pigment, and it's organic.

"If the ink manufacturers would just tell what was in the ink rather than keeping it a secret, that would go a long way towards legitimizing inkjet printing. No artist paint manufacturer would try to sell ink or paint that didn't say what the pigment was.

"Painters used stuff like Alizarin Crimson, a.k.a. Turkey red or Mordant red 11, that faded away to nothing. Now painters are much more careful, yet I have never heard of anyone asking what pigments were used in a million dollar painting, and I doubt most artists would say. Most painters I know are more than a little proprietary about some of their pigments.

Crabby Umbo: "Regarding the word 'archival,' I remember calling the rep of a slipcase portfolio company because I found out the item wasn't made out of inert and safe material, and it it was labeled 'archival.' When I told them of my concerns they said: '...Well, we think it's made pretty well....' Didn't get it at all...."

Tuomas: "I understand the need to raise the status of 'archival inkjet prints,' but how about just calling them 'prints'? You know, like cellular phones are increasingly just phones and digital cameras are cameras."

Joe Holmes: "Wait a minute. Are we brainstorming a solution without a problem? Who's being duped by this 'dye ink with some pigment added'? Where are the collectors demanding refunds for fake archival prints? Where's the outcry that's being addressed? In my walk through this year's AIPAD show in NYC I saw plenty of inkjet prints selling for high prices."

Bron: "In my painter's hat, I own books on materials and methods dating back almost three-quarters of a century. Even the oldest offers advice on permanent pigments, fugitive pigments, and advice on admixtures that may cause problems.Pigments now all have color index numbers, as well as ASTM International permanency numbers, and most mixed artists paints have the index numbers. I can put together a palette that is completely permanent, based on permanent pigments. Doing that for inkjet inks would be a step in the direction you're advocating, and might lead to different palette choices of inksets, so an artist could choose certain colors balanced against permanence."

Michael Bearman: "I disagree. Standardization will create a race to the bottom, as everything at or above the minimum standard will be necessarily be equal (whether or not that is so); hence, it will be in manufacturers' interests only to build to the cheapest minimum. In any event, when has the longevity of art ever had anything to do with its value? Van Gogh's colours today are more than a bit different than when freshly painted. And Museums and galleries are stuffed to the gills with paintings, prints, etc. that cannot be removed from controlled environments."

Robert P: "I went to an opening of a photography exhibition where the prints were selling (and they did) for thousands. The photographer would not admit that they were inkjets, even though I knew that he had printed them himself on an Epson or an HP (I forget which). He was very insistent that they were not ink, but pigment, and he seemed to think I was trying to catch him out whereas I simply wanted to know what he had printed with, as they were stunning. One of the only times that I have seen a gallery be totally open about it was an Eggleston show in London a few years back when I was told they were Epson prints. I guess Eggleston was big enough for it not to matter."

Pete: "Think I'll just stick with Pigment on Paper. It doesn't sound like something someone in a lab came up with."

MHMG [Mark from Aardenburg Imaging —Ed.]: "I'm no stranger to certifications and the like. But honestly, artists will not and should not be subject to certifications. They should use whatever materials they wish to when creating their work. Likewise, museums and archives should never impose a litmus test of any kind for what is deemed worth collecting (and to my knowledge, with the exception of the personal tastes of individual curators, they don't).

"What is needed is a central database of P+I+P (actually P+I+P+C, where C is any possible further treatment like a coating) that informs both artist and collector of the fragility (or lack thereof) of the final work, and gives insight into what kind of optimal care is needed to care for that historic and/or artistic work over time.

"Consider the seminal work The Pencil of Nature by Henry Fox Talbot. If I were to run Talbot's 'Calotype' process through the Aardenburg light fade testing protocol it would probably receive a shockingly low rating of less than 1 megalux hour (six months or so at the industry-standard assumption of 450 lux for 12 hours per day) because the salted paper prints tipped into Talbot's book were all made before Sir John Hershel suggested sodium thiosulfate ('hypo' or 'fixer' to those of you old timers who remember spending time in a photographic darkroom) as a means to remove the residual silver halide crystals from the print. Competent museum curators understand that this early historic print process is light sensitive and have implemented strict policies to ensure that it's inherent fragility is 'rationed' for future viewing audiences wisely. As such, The Pencil of Nature, a work of art that we might 'certify' to last only six months in these modern times is still with us (albeit only about a dozen copies remain) after more than 175 years. I hope folks can now understand why Aardenburg Imaging and Archives doesn't try to reduce light fastness testing to a simple 'years on display' rating. The end-user or collector has a huge role in creating appropriate storage and display environments, and thus has a major say in how long a print will last."