The whole Eggleston-Sobel imbroglio is, to my mind, simply another reason why photographers should never limit their editions.

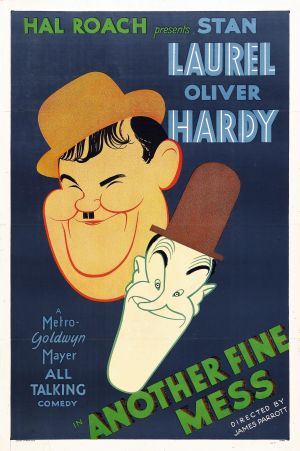

Imbroglio is a word I like: it's pronounced im-BRO-lee-oh, and it means "a confused heap." It's what Oliver Hardy means when he says, in no fewer than 15 Laurel and Hardy films, "Well, here's another nice mess you've gotten me into!" (He never actually says "another fine mess"—that was the title of a 1930 film.)

Whenever the subject of limited editions comes up, I'm quickly admonished that "you have to limit your editions" because dealers want you to and the art market expects you to. Well, of course they do: it's to their advantage. The practice of limiting editions exists almost exclusively to benefit the secondary market.

Whenever the subject of limited editions comes up, I'm quickly admonished that "you have to limit your editions" because dealers want you to and the art market expects you to. Well, of course they do: it's to their advantage. The practice of limiting editions exists almost exclusively to benefit the secondary market.

Actually, you don't have to do anything. You have a spine, and it's a free country. Do what you want, not what some art-world autocrat demands that you do. Act in your own best interests instead of someone else's.

Another brief digression, for a few definitions: the primary market is when the creator—the photographer who took the photograph—sells a print of it to someone. The secondary market is when that other person re-sells it to someone else.

At this point in the discussion, someone always says, "Limited editions only benefit the secondary market? No they don't. Limiting your editions helps you sell more prints, because collectors are more likely to buy prints from limited editions."

That's right. Limiting the edition size does help you sell a few more photographs—except in the case of your most popular photographs. Which are the ones that will make the lion's share of whatever money you'll ever earn from print sales. And as every photographer knows, those most popular photographs are few and rare. In those few, rare cases—when you've actually created a desirable picture lots of people want to buy—you don't need any "help" selling out the edition. People will buy them because they want them. And then they will want some more.

And therein—there in those words "and then they will want some more"—lies the rub. The demand goes on—sustained, even after the edition has run out. It might even go up. The demand is greater than the supply.

This is what the secondary market prizes, and why it cares. High demand + low supply = higher prices. The secondary market only profits if the prices go up as work is resold again and again.

To help this to happen, the secondary market has to make sure the supply is controlled—even if it has to be done artificially. Dead artists are mighty tractable in this way; they don't make any more prints and they don't sign any more prints. But living photographers are loose cannons. Never know what they're going to do. So living photographers are bullied into limiting their editions.

All this means to the photographer is that he or she is going to be prevented from profiting from his or her desirable photographs. His or her few, rare desirable photographs, mind you...the ones he or she doesn't have many of.

So here's how it goes. Luck, skill, and hard work pay off, and you get a really outstanding shot that lots of people might want to buy. And what happens? You're enjoined to only sell a few of them, for the sake of the secondary market. Your ability to profit from sales of prints of your photograph is limited right along with the "edition."

Why would photographers want to do this? Because they're told they have to.

Photographers should want the primary market to profit, not the secondary market. The reason is simple: that's you. You are the primary supplier for your own photographs. If you sell a print for $350 and 10 years later it sells for $10,000 on the secondary market, you don't get a piece of that $10,000*.

At this point in the discussion, somebody always says, "Wrong. Because if the prices for your older work goes up on the secondary market, it will increase the prices you can charge for your newer work." Right again. That works...for about seventy people alive in the world today. Maybe fifty. Or maybe thirty.

It doesn't work that way for most of us.

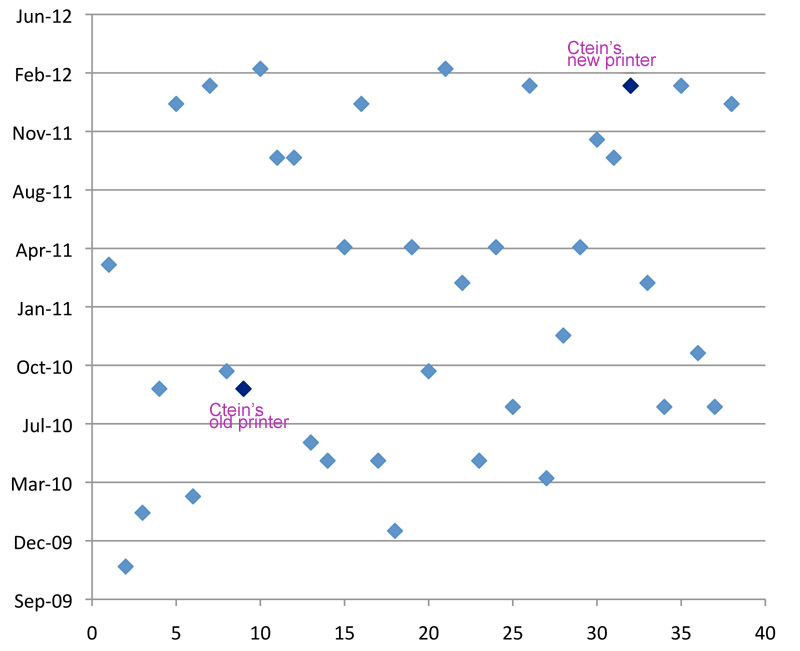

For most of us, you have to look at it from the opposite perspective. Some while ago I mentioned a classmate who took a popular photo of a couple of white cows in the fog on a country road when we were in photo school in the early '80s. She told me she's still selling prints of that picture, 30 years later! I always trot out this next fact in this argument, but that doesn't make it any less true: Ansel Adams printed more than 800 copies of "Moonrise, Hernandez," in his life, his best-selling photograph. That didn't stop it from holding the auction record for a photograph at one time.

Then consider the handful of photojournalists I've heard from in my tenure as an editor, who took one or two famous pictures in their career, but who can't profit from them because the pictures are owned by the publication they took them for. Even some of those who do own their (remember, few, rare) most desirable pictures end up fighting with their former employers over the rights.

Lee Friedlander refuses to limit his editions. Why? You'd have to ask him, but I presume it's because it's anti-democratic and inorganic, not in keeping with the true nature of the medium. And he does as well as anybody in terms of print sales, among photographers of his (considerable) stature.

I'm not objective about this subject. I resent the whole idea of limited editions. It's corrupt, and exploitative of photographers. It's also false—the grafting of a sensible idea from one medium (printmaking) on to a medium to which it does not apply.

First editions

Forget printmaking, from whence the idea of "limited editions" comes. Photographic prints are more like printed books.

Here's my suggestion: go back to first principles. An "edition" is a printing...an occasion on which a work is published in multiple. It is in that sense necessarily limited, because you don't print an unlimited number of photographs or print an unlimited run of books when you make up a batch of 'em. You don't create unlimited numbers of whatever it is you're publishing, even if you can.

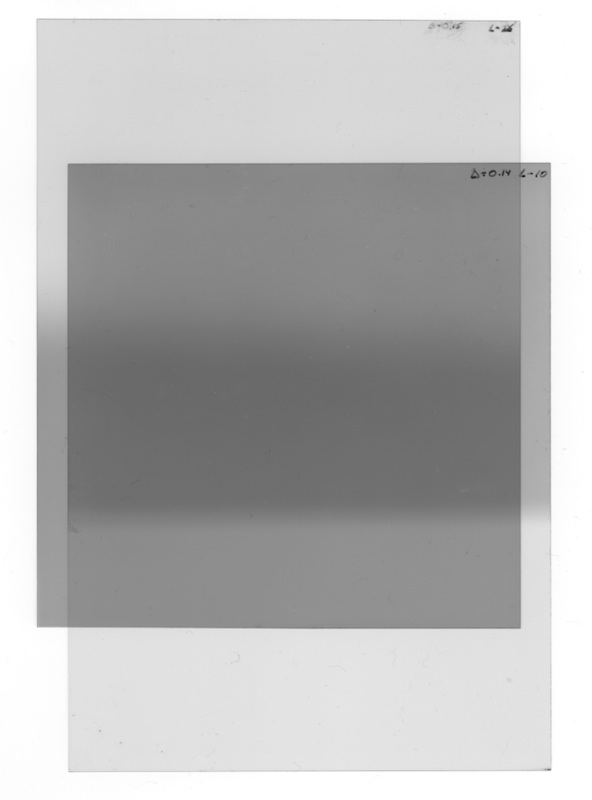

If David Vestal went down to his darkroom in 1986 and printed five copies of a picture he took in Mexico and put them in a box, where they sit for decades, that's a de facto edition. The 1986 printing of that photographs is limited to five. But maybe that picture gets published in a book and suddenly becomes famous, and he quickly sells all his 1986 prints, and he prints 25 more in 2013. He sells nineteen of them and puts the other six in a box, where they will sit for some unspecified period of time. That's the 2013 edition, and it's limited to 25 prints.

Why not just formalize this? Call the 1986 prints "the first edition" and the 2013 prints "the second edition"?

Works for books.

Would Jonathan Sobel be so aggrieved in the current imbroglio if he had bought a print of "Memphis (Tricycle)" that was part of a 25-print** first edition instead of a 25-print limited edition? Would he care so much that the Egglestons decided to raise some cash years later by selling a few big inkjets as a "second edition, 2012"?

I don't think so.

So that's my recommendation. Limit your editions, sure, but do it by being rigorous about it. Print all the prints in the edition at the same time so they're identical and they can all be legitimately identified by a date or a year. Mark them as being part of that edition. Give each edition clear identifiers—size, materials, technique. Don't add any more to that edition after the fact—respect the edition's integrity. Then, if you want to, or if you ever have reason to, do another edition...in which the prints are identifiably different from those of the first edition. Call that other edition the second edition, and mark it as such, and respect its integrity as well.

Problem solved, if you ask me.

Of course, no one asks me. But you can't blame me for trying.

Mike

*Unless you live in France, if memory serves.

**I don't actually know the real number. I made up "25."

Original contents copyright 2013 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

TOP links

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

[Another] Mike: "As a book collector and hobbyist photographer, all of this seem to me to be completely obvious. Most of the time, in publishing, 'limted editions' are little more than a gimmick to get people to spend more money. I'll keep my first edition of The Grapes of Wrath, thank you, no matter how fancy your leather bound, smyth-sewn limited edition is."

Marco: "In Italian, imbroglio refers to a mess made on purpose to obtain something dishonestly. Like selling the Coliseum to an American tourist. ;-) "

Alexandre Buisse: "Talk about being bullied: in France, where I am a pro, it is a legal

requirement to edition your prints to 25 copies or less if you want to

be considered an 'artist,' which comes with all sorts of benefits and

drawbacks, like the ability to license a photograph to a client.

If you refuse to, that makes you a craftsman, you have a higher sales

tax, and you're only allowed to shoot weddings and sell images as

physical objects to the general public.

I wish I was kidding."

Geoff Wittig: "I'm not sure if the analogy with book 'editions' is quite right. Photographic prints can be produced basically on-demand, while book editions really have to be printed all at once due to the economics of a press run. Yes, there is frequently a steep price premium for older 'first editions' of books that become popular, just like there is for older photographic prints. But I regard the obsession with collecting 'first editions' of trade hardcovers completely absurd. There is generally nothing objectively special about such first editions; they're often printed on low quality (i.e., not archival or acid free) paper. The typography is generally ordinary, which is to say dreadful. The 'value' of a first edition, then, is entirely a matter of contrived scarcity rather than artistic merit. I honestly just don't understand this.

"A book that is printed as an actual, honest to goodness limited edition is a very different beast. It generally has been printed on acid-free paper chosen for very specific æsthetic goals, with typopraphy and page design intended to honor and illuminate the text. Such books are often exquisite examples of the very best the bookbinder, paper-maker, typographer and illustrator are capable of. They're actually worth owning for æsthetic, rather than pecuniary, reasons. And because of the labor-intense nature of such books, they're by definition produced in very small numbers. I guess one could regard them as the bibliographic equivalent of a hand-made dye transfer print as opposed to an offset press poster."

Nick Moore: "Don't you think most photographs sold (in the primary market) today are

essentially editions of one—printed on demand rather than in a batch

(or edition)? Your print sales would be notable exceptions and, of

course, are predicated on the benefits of dealing with a batch run. If

true, does this change your thinking about what would constitute an

edition?"

Mike replies: I'm only suggesting this as a rational alternative for those who insist on editioning in the first place. Of course the sensible solution is not to edition at all; see the first paragraph.

tex andrews (partial comment): "...Although Mike makes some excellent points about who benefits in these 'limited' situations, limiting an edition is not altogether illegitimate—because the dealers actually have a legitimate stake in this. They are after all bearing the financial burdens of their businesses, from staffing and rents to utilities, and are indeed giving the artist a value add of marketing, if they are worth their salt. Getting with a good gallery is a very important part of the making of a career—which is very different than the making of the work or developing a vision, etc."