(Continued from Part I)

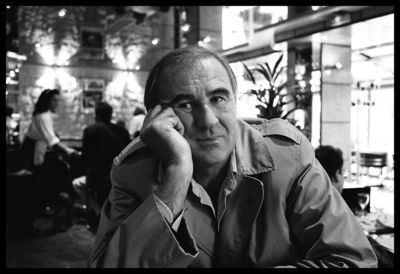

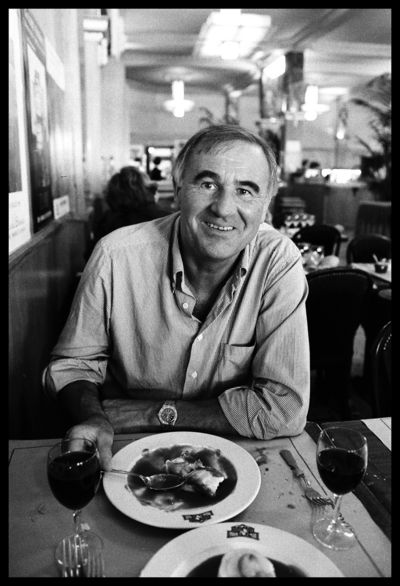

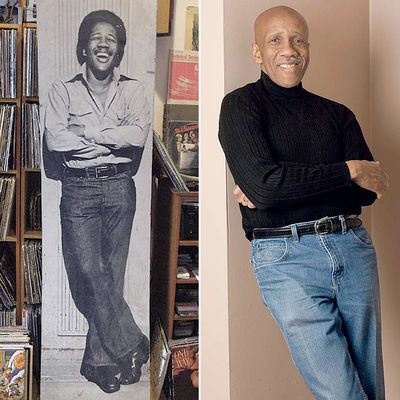

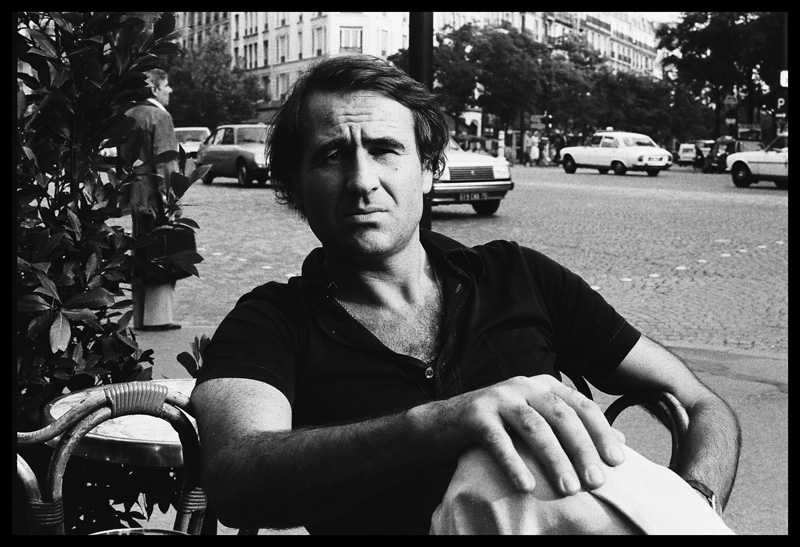

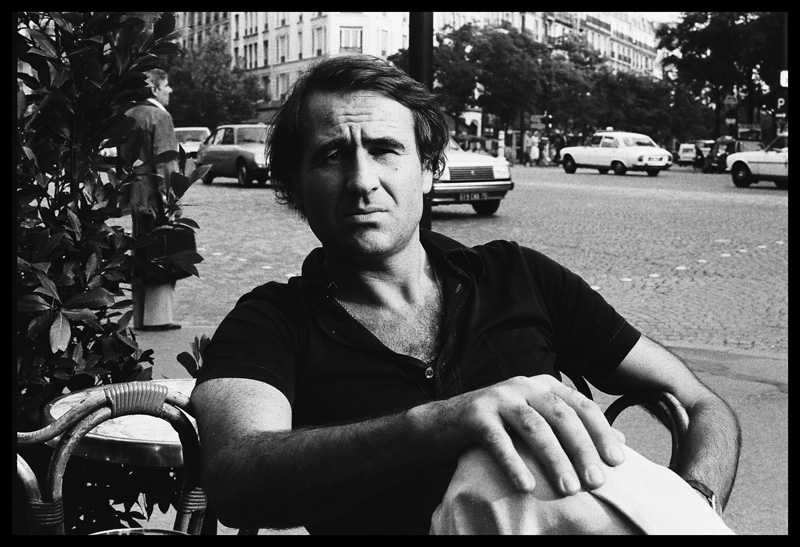

Voja Mitrovic, Montparnasse, Paris, 1982

Voja Mitrovic, Montparnasse, Paris, 1982

By Peter Turnley

I recently sat down and interviewed Voja Mitrovic for several hours about his experiences as a printer. Several important concepts emerged from this interview. He indicated to me that the three most important things involved in being a great printer are patience, developing a good dialogue and communication with the photographer he is printing for, and knowing how to read a negative. It is most important to know the photographer, to know what he or she wants, and to be able to read the image—like photographers, some people see things, and others don't! Great printing involves knowing how to choose the right paper, having technical skills, and a strong artistic and aesthetic sense. He feels that it has helped him very much to have been himself a photographer, in order to understand the goal of a photograph.

Voja gives credit to Josef Koudelka for having helped him become as great a printer as he is. This is because of how demanding and exigent Koudelka has been in what he wants from a print. Koudelka’s prints are very different than Henri Cartier-Bresson's. Cartier-Bresson’s prints are very low contrast with many details in the highlights and shadows—H.C.-B. liked the tonal values of his prints to be like the "color of the Loire River." Gray, but a very detailed gray. Also, Cartier-Bresson’s negatives were, overall, extremely well developed by Picto over the years and in general very consistent. Voya says an exception to this consistency was his early work in Mexico and India, which are among the most difficult of his negatives to print. Koudelka, on the other hand, has demanded prints with relatively high contrast, and yet with detail in both the extreme highlights and in the shadows. On top of this, the development of his negatives in the early years was often very irregular, and the film he used while he was living in Czechoslovakia, before going into exile in 1968, was often cinema stock and very high in contrast. The highlights often become very blocked up. In many of Koudelka’s negatives the tonal range between highlights and shadows are extreme, requiring tremendous "maquillage," or burning and dodging, to achieve contrast and detail to his liking.

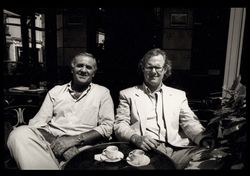

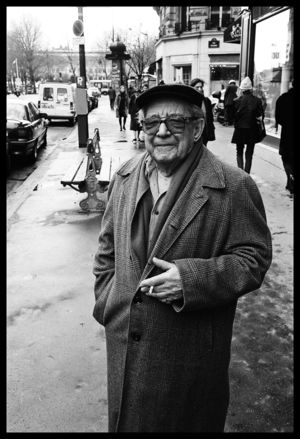

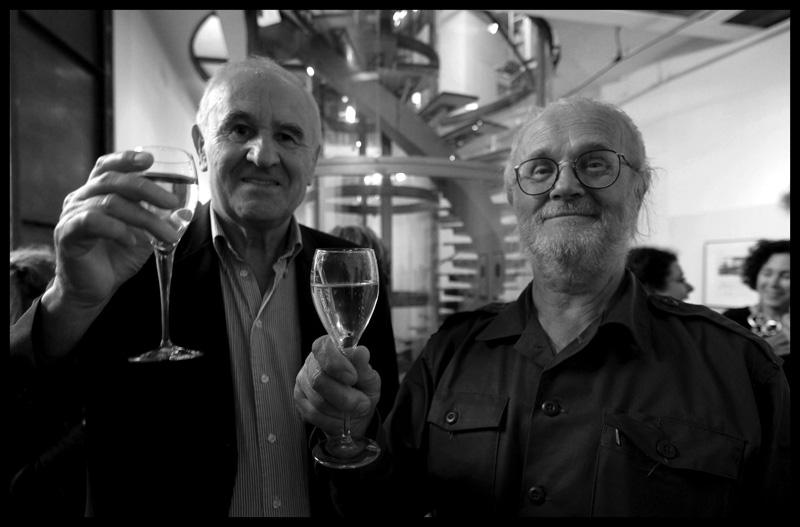

![006[2]-s 006[2]-s](../../../../a/6a00df351e888f88340133f31e16b3970b-300wi.jpg) Voya says that Koudelka’s prints have been 10 to 100 times more difficult to make than H.C.-B.'s. He recalls that at one point, after Koudelka first began to bring his work to Picto, Pierre Gassmann (that’s me with Pierre in 1995, at right) specifically designated Voja to print his photographs, knowing that he would have the physical and mental courage to meet the rigorous and precise standards of Koudelka’s printing demands. He feels that he and Koudelka understand each other well because of their common origins from Central Europe. He is very proud of their friendship. He indicates though that they have an understanding between them that their friendship and his printing are two very separate moments in time—the first always warm, but, while printing, the atmosphere is always one of clear minded, very demanding rigor. Voja recalls how Koudelka’s respect and confidence in his work was once solidified when he showed Josef a print and Koudelka was very satisfied, but Voja said that he was going to start over, because he knew he could take the process further and pull more out of the negative. This is a domain where Voja prints are exceptional—few people know how to pull as much out of a negative as Voja, and few would have also the physical, mental, and emotional courage and determination to do it.

Voya says that Koudelka’s prints have been 10 to 100 times more difficult to make than H.C.-B.'s. He recalls that at one point, after Koudelka first began to bring his work to Picto, Pierre Gassmann (that’s me with Pierre in 1995, at right) specifically designated Voja to print his photographs, knowing that he would have the physical and mental courage to meet the rigorous and precise standards of Koudelka’s printing demands. He feels that he and Koudelka understand each other well because of their common origins from Central Europe. He is very proud of their friendship. He indicates though that they have an understanding between them that their friendship and his printing are two very separate moments in time—the first always warm, but, while printing, the atmosphere is always one of clear minded, very demanding rigor. Voja recalls how Koudelka’s respect and confidence in his work was once solidified when he showed Josef a print and Koudelka was very satisfied, but Voja said that he was going to start over, because he knew he could take the process further and pull more out of the negative. This is a domain where Voja prints are exceptional—few people know how to pull as much out of a negative as Voja, and few would have also the physical, mental, and emotional courage and determination to do it.

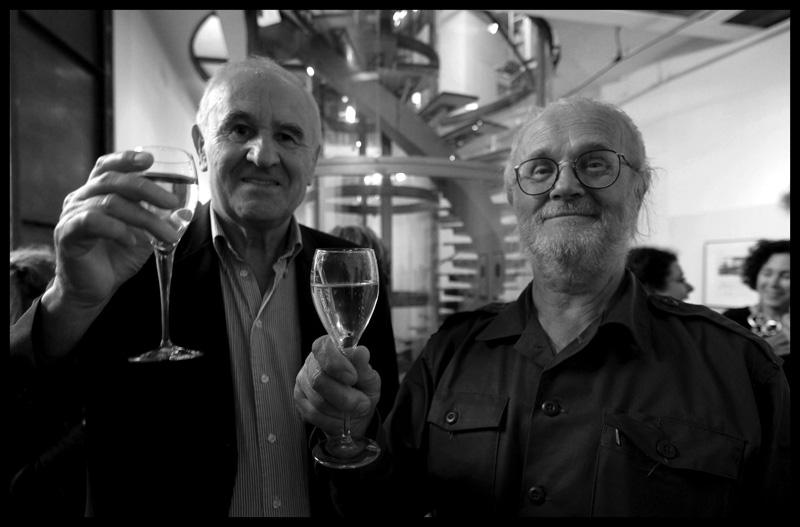

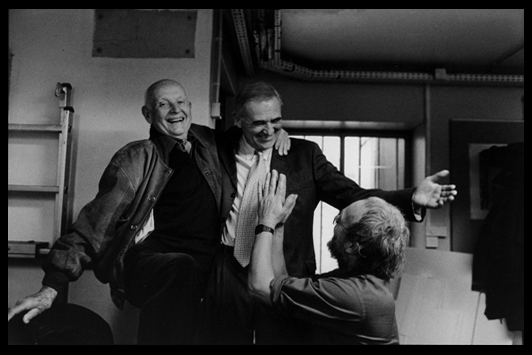

Voja Mitrovic and Josef Koudelka at Magnum, Paris, when John Morris was awarded the French Legion of Honor, 2009. Photo by Peter Turnley.

Voja Mitrovic and Josef Koudelka at Magnum, Paris, when John Morris was awarded the French Legion of Honor, 2009. Photo by Peter Turnley.

Voja is very proud of the relationships and friendships that he has developed with the photographers he has worked with. These relationships have also offered one of life’s most important gifts—the opportunity to travel. He had been invited by photographers, as thanks for his work, to New York, Mexico, Rome, Barcelona, Crete, China, Cuba, and Barcelona.

He is very proud to be among the first printers to be credited by name for his role in printing the photographs in books of photography and exhibitions. This had almost never happened before the early 1990s when photographers began to credit Voja in their books and exhibitions for his printing. The list of books and books for which he has been credited is astonishing. It includes almost all of the books and exhibitions of H.C.-B. since 1966, including Vive La France, Henri Cartier-Bresson in India, America in Passing, Henri Cartier-Bresson: Photographer, Mexican Notebooks, and Paris a Vue D’Oeil. He has printed the exhibitions and books of Josef Koudelka for Exiles, Triangle Noir, Koudelka, and Chaos. He has printed both the books and exhibitions of many others’ work, including all of my books and the exhibition and signed collector prints of my photographs.

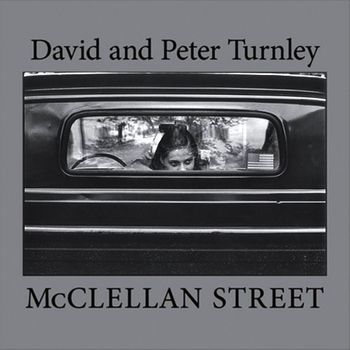

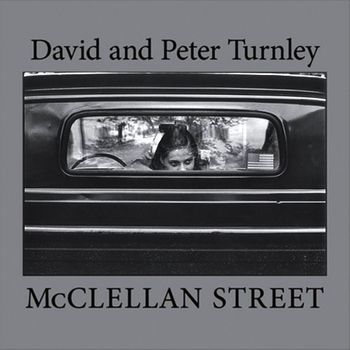

The book I

did with my brother David of our early work, one of many for which Voja made the

master prints. Voja has said that my cover picture here is his favorite

picture of mine.

Anyone who has taken my Paris Street Photography workshop has been treated to an amazing presentation by Voja. My guess is those lucky few to have witnessed one of his talks will never forget seeing the demonstration Voja makes of showing a sheet of photographic paper of a H.C.-B., Koudelka, Burri, or Turnley "straight" print, exposed only once with no burning and dodging, held up next to a final print showing all of Voja's artisanry. It is a phenomenal sight to see—and a powerful indication of the degree to which a great printer like Voja has contributed immensely to the expression of the vision of the photographer. I have witnessed Voja many times spend at least one hour of physical burning and dodging of a print. I've also seen him be able to repeat perfectly, like a machine, the exact same gestures and make a series of ten identical prints from the same difficult negative.

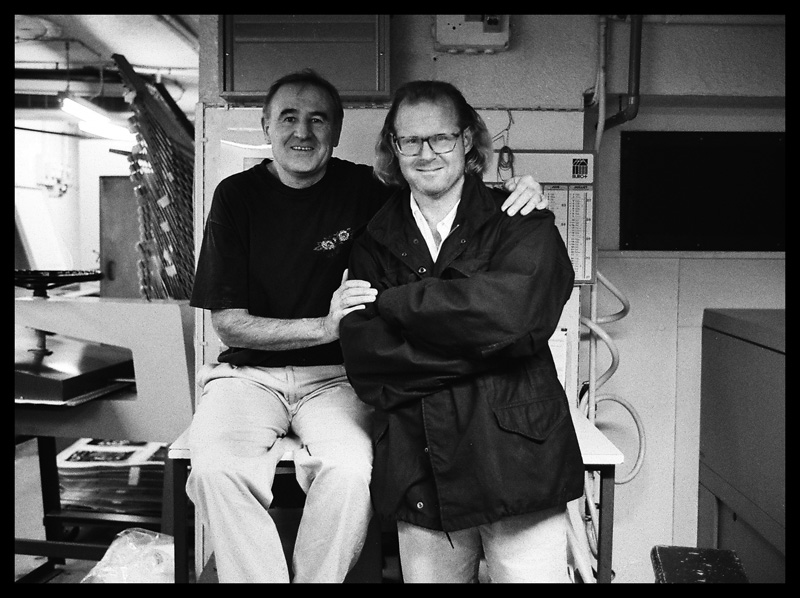

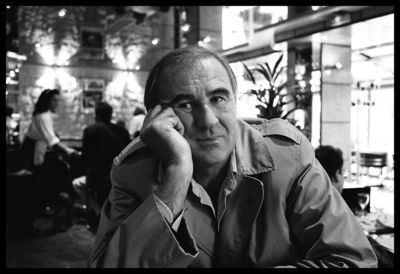

Peter Turnley, Josef Koudelka, and Voja Mitrovic at Picto, Paris, 1996

Peter Turnley, Josef Koudelka, and Voja Mitrovic at Picto, Paris, 1996

While Voja has indicated that Koudelka’s prints have been the most difficult for him to make, there are several famous images of H.C.-B. which require tremendous burning and dodging—such as the image of the nuns praying in India. Koudelka’s image of the man and the horse and one of a street scene of a man setting off a fireworks rocket are among those of Koudelka's that Voja has commented are among the most difficult to print.

It is hard to imagine the physical and mental stamina and courage required to be a great printer. You are in the dark with very low light for at least eight hours a day, exposed to the odors and effects of rather strong chemicals. I recall the feeling of walking out of Picto after a long days work, and being suddenly exposed to the late rays of an afternoon summer day, literally feeling off-balance from the physical impact of such a sudden change in environment. I have rarely met anyone who appreciates his annual summer vacation like Voja. He loves to lie on the beach and soak up the sun—which seems to rejuvenate his body after spending so much of the year inside without much light.

Voja is a tall and athletic man always in great shape. I'm sure this has been extremely helpful in his work, which is not only mentally but also physically extremely demanding. You should try to stand under an enlarger with your hands lifted in the air burning and dodging with methodic consistency for one hour for only one print—and then repeat that some times ten times in a day. Each weekend, since coming to Paris in 1964, Voja played on a soccer team on Sunday mornings. He tells me that this enabled him to unwind from a week of stress and revitalize himself for another week of work ahead. He has also always been a wonderful family man, with a wife and two children, and he has a strong appreciation for good food. While I was at Picto, it was always impressive to see the regularity in which Voja would arrive each morning exactly on time, impeccably dressed, and then change in to his work clothes and begin printing. Each day at exactly noon he changed back into his street clothes, and, looking like a handsome movie star, struck out into the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris for his daily ritual of a very good lunch. At the end of the day, at 5 p.m. sharp, he stopped work, and would go to meet his friends at the Café Cosmos for a bit of conversation before heading home for dinner.

Finally, anyone who has ever met Voja, has been certainly struck by several rare characteristics. He is one of the most elegant, truly dignified people one will ever meet. He exudes a rare unpretentious dignity of someone that has led a hard working, decent life, and has cared for his family and friends, and put his heart completely into doing his work as well as he can. His spirit is infinitely fair and generous—when asked who is his favorite photographer, he will always refuse to answer, preferring to indicate the favorite image of each photographer for whom he has printed. He cites "La Rue Mouffetard" and "Matisse with pigeons" as his favorite H.C.-B. images. The man with horse is his favorite image of Koudelka, the image of Che Guevara and the cigar, his favorite of Rene Burri's, and my cover image from McClellan Street seen above is his favorite image of mine. While he has printed for so many great photographers, there are a few he wishes he could have printed for—Robert Frank, Alvarez-Bravo, and Irving Penn. He chuckled as he told me he had recently visited a Robert Frank exhibition in Paris and thought it could have been printed better.

It is likely that with the change of technology towards an all-digital world, that the world will never again know many traditional black-and-white printers like Voja. He worries that all of the technological know-how in the world will not replace what it first means to know how to make a photograph, and then to know how to read a negative and interpret it. There have been already few traditional printers that could do it as well as he could. He recounts how Josef Koudelka has spent in recent years more than six hours with a digital printing technician trying to achieve a match with the subtle artistic expression of tones and detail in one of his prints. He also worries about how long good traditional silver printing paper will continue to be made and laments how expensive it has become.

Voja Mitrovic, Paris, 1993. Photo by Peter Turnley.

I have met with Voja for coffee almost every Sunday morning I’ve been in Paris for the past twenty years. Each time I leave our encounters, my heart is uplifted—I am reminded of what seems important to me—and I feel proud that I have chosen a way of life and a medium of storytelling that has enabled me to know and work with a person with his elegance, dignity, strength, and decency. And, I am sure that I would be only one among a list of photographers who would say that he has been one of the best and kindest friends one could ever ask for.

The world of photography has been lucky to have Voja, and all of the other great printers that have meant so much to the powerful expression of moments photographers have chosen to share with themselves and others for now, and for posterity. He has spent his life in the dark, but he has helped illuminate the life and expression of so many. Thank you Voja.

Peter Turnley

Paris, August 2010

Please send this post to a friend!

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2010 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

Featured Comment by

Stan B.: "'...but few would have also the physical, mental, and emotional courage and determination to do it.' Yeah, I definitely came up short on that end, despite all the blood, sweat and tears I still managed to shed in the dark. But to be blessed as a so called 'natural,' I guess that's where the 'joy' of the darkroom really came in. For many of us it remained a war...."

Mike responds: Stan, I always used to say, "sometimes you win, sometimes the darkroom wins." Voya's comments about patience and equilibrium and just treating it as a job to be done—stoicism, he's describing—really resonated with me.

Featured Comment by

Jim Richardson:"Having done a little bit of printing for a couple of decades, the phrase that really rang out, Peter, was citing how Voja could repeat the same 'gesture' consistently.

"Those who have never printed under an enlarger may not know what this means. But once you see someone dodging and burning a print, once you see the ballet-like gestures of the hands in the light of the enlarger, precisely casting shafts of light onto the paper through hands formed into narrow apertures, deftly changing the shape of those openings through the course of the burning, gently moving the light to the edge of the paper to add edge burn (and thus create a glowing center), burning with one hand while dodging with the other, all the while keeping a running count of each adjustment so that it can be repeated (and adjusted), then you understand why one printer can be so much better than another, just as one pole vaulter can make it over the bar, and another can't. It's that physically demanding.

"And that doesn't begin to address the way an excellent printer looks at the negative and begins to form a plan of attack, of correctly identifying the biggest problems in the negative and addressing that first, and then inventing solutions to the subsequent problems thus incurred. Koudelka's negatives would be a particular problem because he wants (needs) contrast in the shadows which demands higher contrast paper, just what you don't want to use when you have a negative with blocked up highlights. But that problem can be solved with sufficient variable burning of the highlights. After all, any high contrast paper can theoretically be made perfectly 'flat' with sufficient burning and dodging, a fact that Voja seems to know very well. (And if I'm not mistaken that's exactly what he has to do on that picture of the nuns praying in India.)

"All of this requires 'gesture,' as you point out Peter, and not everyone has that level of subtle grace in their movements. Thanks for bringing this story to light and thanks for reminding me of beauty of craft seen only in the light of an enlarger, where hands shape light as gracefully as a nuanced ballet."

[Jim's most recent National Geographic photo essay, on the Hebrides islands (website—>Cultures—>Hebrides), was published in the magazine last January. —Ed.]

Featured Comment by V.I. Voltz: "Someone asked whether Voja printed the originals for Salgado's book Africa [now out of print and rising in price—don't say I didn't warn you! —Ed.]. At least some of those were printed by Nathalie Loparelli. the negatives were in her darkroom when she did some work for me years ago.

[now out of print and rising in price—don't say I didn't warn you! —Ed.]. At least some of those were printed by Nathalie Loparelli. the negatives were in her darkroom when she did some work for me years ago.

"Which is also the amazing thing about Voja. The first time I was in Paris in 1995 I was 20 and thought I was good. So I walked to Picto, explained that I didn't speak French, but that I wanted some printing done and that I would like to speak to the printer, who, it turns out, was Voja. I had no idea who he was. He took me completely seriously, even though I am sure he could tell I was a total hack, and later commented that he liked one of my photos. Voja, of course, did an _i_n_c_r_e_d_i_b_l_e_ job of printing them. They sparkle and practically jump out of the paper at you. With those prints I managed to talk my way into a job that I had on and off through the next four years.

"In 1995 if you'd told me the next print that Voja would make after mine would be a Cartier-Bresson or a Koudelka, I'd have thought I was good. Knowing what I do now, I'm just astounded at Voja's understanding, accommodating approach and sheer professionalism."

Featured Comment by Jay Colton: "Thanks Peter. I have seen the craftsmanship in Voja's work. Being a fair printer myself, I greatly appreciate his craftsmanship and share in his lamentations. Silver printing is now made more difficult as the papers are disappearing. I print on Oriental Seagull but I miss the graded paper; the G is O.K. but I for one am not a fan of multigrades. In addition the chemistry is harder and more expensive. Thank God for Photographers Formulary.

"On many occasions, I have explained in detail how I print only to see someone follow the letter and not the spirit of instruction. I understand it takes a kindred spirit to really craft a print. A printer must look into the negative and see your soul. As a photographer your negatives capture the moment but a great print recreates the moment in its own special poetry. If I don't print the image myself I have found it takes years (or a kindred spirit who sees through my negatives into my soul) to develop a relationship with a printer who knows what you want out of the negative and into your print. Silver prints are like little jewels that contain their own special reality. When we shoot in B&W it is not a 'true' depiction of the world; it is an allegorical fantasy in shades of gray where form elocutes a special magic.

"The mastery of printing like any craft requires dedication. It s only after a great deal of time (Malcolm Gladwell quantifies it as 10,000 hours) that a true mastery is possible; where the intuition is innate and the gesture (as you put it so eloquently) poetic. Alas I have not put in the necessary time but I do so admire those whose craft has become natural like breathing. Like any artist they make it seem effortless (and it is, for them) and free.

"I most enjoyed your relating his ethic that it is just work, no more or less. That honesty is the mark of a master craftsman the humble beauty of work unencumbered by artifice. Thank you for relating the little-known story of the invisible hands that great photographers trusted their precious images to. It is truly sad to see the last craftsman (both shooters of film and the master printers) slowly fade into the dustbins of history The world is poorer and a little darker without them. I only regret that I did not have the honor of having him print my own images."

![006[2]-s 006[2]-s](../../../../a/6a00df351e888f88340133f31e16b3970b-300wi.jpg)