Ctein reports that all prints from my sale have shipped as of this morning. Everyone should have received an e-mail with a tracking number from the post office. Sometimes cyberspace is slow; if you haven't received notice by Monday, please e-mail Ctein ([email protected]). You can track the progress of your order on the post office website using the tracking number.

And thanks very much!

The June Print Offer, a Leica S Series "example print" by Jack MacDonough, will start on Monday morning at 7 a.m.

How TOP print offers work

Jack went back and looked, and discovered it's actually been quite a long time since I've explained how our print offers work. This might be a good time to revisit.

Our TOP print offers grew out of a program I initiated at Photo Techniques magazine called the "Collector Print Program." That, in turn, was inspired by Fred Picker's "Example Prints" that he offered through his business Zone VI Studios in the 1980s.

The fundamental principle is that it's good to see things for yourself, with your own eyes.

Picker produced 8x10" contact prints in bulk and sold them for very low prices through his equipment catalogs. He simply reasoned that most people had never seen an 8x10" contact print and didn't know how good they looked. Although the prints typically cost only $25, he claimed at one point that he was one of the very few photographers in the U.S. who was selling more than $100,000 worth of prints annually.

Usually, the prints we've offered have been nice pictures in and of themselves, but they also do double-duty as examples of various techniques or equipment types. Carl Weese offered platinum/palladium B&W prints; Ctein offered color dye transfer prints several times, as well as an "ideal" large prints from a Micro 4/3 file; and I offered the best digital B&W print that's ever been made from my work. Monday's print "needs no explanation," but we also chose it as an excellent example of what an S-series Leica is capable of, for the many people who've never been able to see for themselves and might be curious.

The standard "gallery model" of print sales c. 1980 (the year I got into photography seriously) was as follows. At the culmination of a period of working, the photographer spent lots of time, money and effort printing, framing, and (usually) helping to hang, and (usually) helping to market, a show. A gallery would display the work for a month or (infrequently) two, during which time a small number of people—dozens or hundreds, and not more than a few thousand at the very most—would see it.

However, they were the right kind of people—the kind of people who went to galleries, meaning people who really liked photographs...

...And sometimes actually bought them. A gallerist in Washington D.C. told me that the largest number of prints she had ever sold from a single show was 60. But that was a bleeding-edge outlier—sales of a dozen prints or even fewer was much more the norm for a month-long gallery show.

The burden of a lot of operating expenses had to fall on the back of these few sales: the gallery's overhead, the gallery director's income, and the photographer's immediate expenses (printing and framing the prints for the show). Naturally the print prices had to be high. I was told in art school in 1982–5 that an acceptable price for a "student print" was $350, and that any mature, working art photographer worth his or her salt should start their pricing at no less than $500, with $750 being a more comfortable base price*. More successful working local art photographers charged anywhere from $800 to $2,000 for a print, with $950 and $1,200, as I recall, being popular price-points.

The photographer's "deep" expenses—what it cost to become a photographer in the first place, as well as ongoing survival—were seldom addressed. Usually, the photographer's cut of the print sale price was 50%. Later, this changed to 40% as a standard, and 30% in a number of instances. (I don't know what's common now, for living, working contemporary photographers represented by galleries.)

The photographer's right to sell her own prints was limited. Those were called "studio sales" and galleries didn't like them, because they undercut the gallery's sales efforts and their ability to profit. (Note however that the galleries weren't getting rich either. Running a gallery was in some ways just as much a labor of love as being a photographer, and many galleries came and went—only the good, savvy, and dedicated ones could survive for more than a few years.)

However, the gallery often didn't do a lot to promote its photographers during the times they weren't having a show. Let's just say prints didn't fly off the shelves. The model was simple: if a print sold, the photographer usually had to go into the darkroom and make a new print for the buyer.

So gallery sales went as follows: buyers could buy a print at any time, but galleries sold very few, the price was relatively very high, the gallery made the majority of the profit, and the photographer had to produce the prints one at a time, intermittently, to order.

(A side effect of this last factor was that many times, buyers had to wait a long time for their prints. When I interviewed Sally Mann in the '80s she had a huge backlog of print orders—which moved me to compare her to King Midas, since she could turn silver into gold at will—and when the publisher of Photo Techniques bought a John Sexton print, he had to wait for it for at least two years that I know of. I think the last I heard he had been waiting for five years and counting, but my memory might be wrong.)

The TOP model

Our model is basically the opposite of the gallery model. We open our sales for a short "window" (currently five days, but soon to change to three). During that time, people who want one place their order and pay for it. When the sale closes, the photographer knows how many prints he or she has to make, and can make them all at once.

In our sales, most of the profit goes to the photographers. I'm the "gallery" (really a promoter or salesman, I suppose). My portion is 20% of the gross. From his 80%, the photographer must bear the expense of producing the print, but the lion's share of the profit is his.

While it's true that the photographer earns less per print from our sales, the big advantage is that every print the photographer makes is already sold. This allows us to offer the prints for much less than equivalent traditional gallery prices.

So, in a generalized way, the "models" look like this, with typical number values inserted:

Typically gallery sale: Prints continuously available; prints sold one at a time, every now and then, for $1,000. The gallery keeps $700 and the photographer gets $300. The photographer must produce and deliver the print to individual order. The buyer might have to wait for it indefinitely.

Typical TOP sale: Availability very limited, during the brief sale "window" only; 100 prints sold, all at once, for $100 each. The site keeps $2,000 (20%) and the photographer gets $8,000. The photographer can make all the prints at once and the buyer receives it within eight weeks.

The disadvantage of our model is that the photographer pays more to produce the prints, since he has to make 100 of them instead of one. (It is indeed a lot of work in a hurry, not for the constitutionally fainthearted.) But he can make them all at once, and his cut is larger to begin with.

The advantage for the buyer is that she's spent 1/10th as much for the print and will receive it within a matter of weeks. The disadvantage is that she can't order it any time, but has to hit the window when the sale is happening.

I like to call this a "win-win-win": I win, because I get 20% of the proceeds; the photographer wins, because he sells more prints and gets to keep a greater percentage of the profits than any gallery would allow; and the buyer wins, because you get a fine print for a very advantageous price, and it arrives with reasonable promptness.

Final note

Our print sales have really amounted to one long experiment, as we try different things and see what works and what doesn't (and what people like and what they don't). Our latest experiment is to try to downplay the sales and integrate them a little better into the quotidian flow of the site. (My conceit is that it should be a feature of the site, entertaining to check out even for those who aren't buying. We'll see if that pans out.)

One thing we've learned is never to show what we're offering until the sale starts. So please stop back on Monday morning after 7 a.m. and check out Jack's Leica S2 print! I'll be interested to hear whether you like it.

Mike

*I had a delightful little thing happen to me before our first Peter Turnley sale. I was out to dinner in the company of, among others, an old friend who teaches photography, Kate, and a local gallery owner, Deb. I was talking about our pricing for Peter's sale, which was the highest amount we had ever asked for prints on TOP at the time. They asked me what the price was, and I said, "$395," at which point—simultaneously—Kate, on my left, said "that is a lot," and Deb, on my right, said "that's nothing."

It's always relative.

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

TOP's links!

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

No featured comments yet—please check back soon!

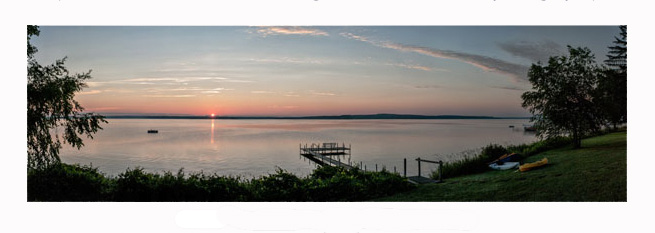

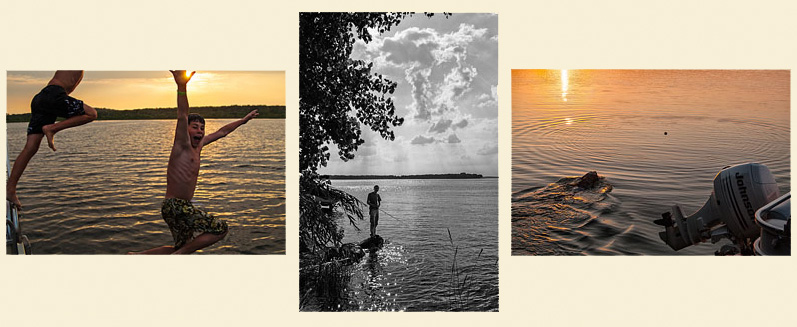

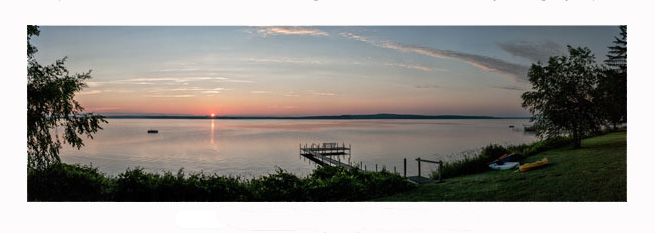

Why a Leica S? Jack MacDonough's 2x3-foot print is intended to let you see for yourself. Taken at Mirror Lake, New Hampshire.

Why a Leica S? Jack MacDonough's 2x3-foot print is intended to let you see for yourself. Taken at Mirror Lake, New Hampshire.