"Sharpness" is a contentious concept in photography. It's undyingly popular, but there are a lot of misunderstandings about it.

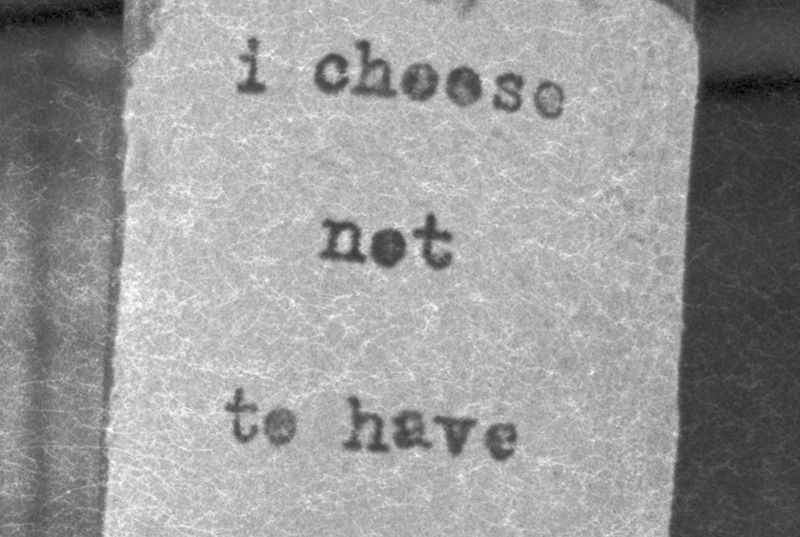

The essential ambivalence or contradiction (duality? dichotomy?) is that technically, sharpness is a goal, and considered a virtue; but aesthetically, it's just a property—no better or worse, inherently, than any other property.

...Even its opposite. For example, we talked about Alvin Langdon Coburn a few weeks ago. Pictorialist photographers prized unsharpness—what Coburn called "diffusion"—and preferred lenses that were unsharp. Sharp lenses were considered utilitarian, and lack of sharpness was considered a hallmark of artistic sensitivity. Nobody who was anybody wanted a sharp lens.

Pictorialism fell out of favor decisively in the 1930s and '40s when it became the prevailing mode of amateurs and hobbyists (and older people, and the hidebound). Its modes and motifs were reduced to cliché and mannerism. Group ƒ/64 (named for an aperture that, on a view camera, helped achieve "pan focus," or sharpness from front to back in the subject) was in part a reaction to that; both Ansel Adams and Edward Weston created gauzy, soft-focus pictures very early in their careers before rejecting it for the hard-edged, highly descriptive techniques of their mature years.

Curiously, though, our preferred technique tends to become part of our value system. It becomes consistent, and persistent. Even pursuing his late, far-out "Vorticist" experiments, Coburn never abandoned fuzzy focus—it was how he liked to see things. Once photographers settle on how they want, and expect, photographs to look—whether it's a contact print from a view camera (as my friend Oren prefers) or black-and-white with a blackline around it (as I love best) or an onscreen JPEG with goosed-up day-glo colors (no names here!), that sense of "rightness" persists. Once settled, technical preferences seem to become part of us.

The history of our own era can't be written for another 30 to 50 years, but, these days, many hobbyists pursue "sharpness" to fanatical excess, as if sharpness and resolution were a marker of some sort of religious or ideological purity or something.

It's gotten so excessive it's actually kind of funny, primarily because most of us look at photographs—regularly, and happily—in forms that don't even allow us to see the level of resolution we're always arguing about. Most of the JPEGs we look at online are well under a million pixels, and fine detail in such small files is mainly only implied. And yet we look at such pictures contentedly all day long. A full resolution picture on a 27" Retina display requires only about 15 megapixels of information. To me personally, a Retina iPad is the nicest way to look at pictures today...and that requires files of only a little more than three megapixels. (I wonder how many people shoot with 42- or 50-megapixel sensors "in case I ever want to print"—but who never actually do?)

Color photography used to be difficult, and the materials slow. We can now easily make sharp, clear, full-color pictures of almost anything, under almost any conditions...ergo, that's no longer enough. Now that "good" technique has become so easy that it's almost a given, people seem to be looking harder than ever for a "magic bullet," some effect which will automatically and reliably impart specialness to their pictures. The best sensor, the best lens, whatever. The sharpest this or the finest that.

Unfortunately, it never was that easy, and it never will be. It's always a judgement call. Always has been, always will be.

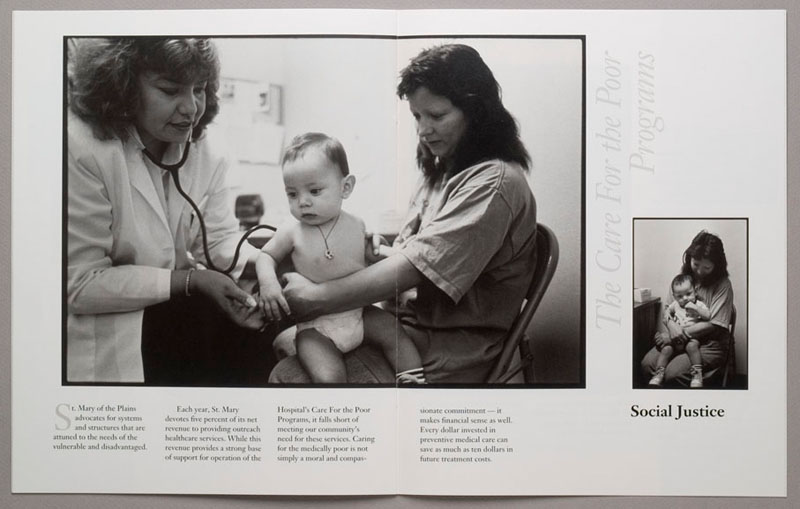

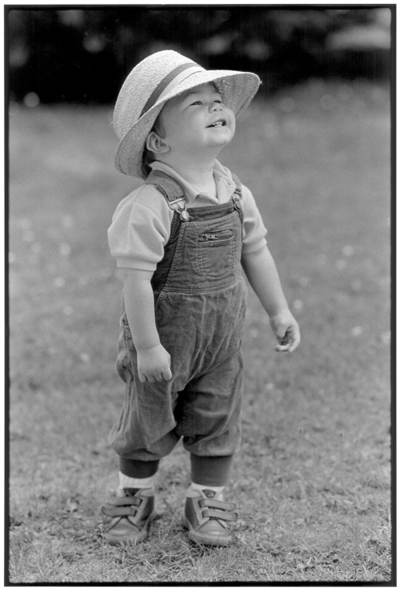

I've always held that fastidiousness in technique is something photographers do for themselves—for their own satisfaction—rather than either for the good of their pictures or for the benefit of their audience, their viewers. Ultimately, what makes a photograph successful is expression and meaning. Technique merely controls the properties we employ to contribute to those things. And technique merely needs to be "appropriate" to the photograph: sometimes "good" technique works best; sometimes "bad" technique works best. But, aesthetically, no specific techniques are virtues in themselves. They're just properties. Today's unrelenting sharpness and hyper-realistic detail, carried to extremes, is just a fashion. It helps some pictures succeed; it ruins others, which could be helped by not being so literal and analytical.

Sharpness absolutely doesn't matter...as an absolute. Technically, it might be fun to shoot for extremes, and be able to achieve them. But aesthetically it's just another property, which might help, but might just as easily not.

Mike

Original contents copyright 2016 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

toto: "I just want my bokeh to be sharp—corner to corner."

Hugh Smith: "A few years back, I wrote what would become a cover article for Shutterbug magazine about pinhole photography. Interestingly, the first correspondence from the editor before publication was 'the images seem a bit soft.' I refrained from my first response which was 'duh,' and answered with 'That’s the nature of pinhole photography.' The images are soft since there is no lens. And that’s what makes them so cuddly. Sharpness is ofttimes overrated. Just my two pesos."

Jim Richardson: "In recent years while teaching our National Geographic Traveler Seminars I often made the intentionally provocative statement that 'Sharpness won't get you published. Content gets you published.' I'd then go on to explain but it was a hopeless task. I could see it in their eyes: 'Blasphemy! Blasphemy!'"

Richard: "I've been shooting with an old screwmount Takumar on my Canon 6D. With one lens I can have gauzy unsharpness at ƒ/1.4 or scathing detail at ƒ/5.6 plus. Almost always like the wide open pictures better; it's my one man rebellion against the hyper-sharp HDR army!"

John Denniston: "Back in the late '60s I was in the darkroom with another photographer who was going over his negs for what seemed a very long time trying to find the perfect frame for one of the humorous setup pictures newspapers were notorious for at that time. I asked him if they were all soft. He said no, they were all sharp, maybe a bit too sharp, and didn't look real. He was looking for one slightly out of focus but that would still read OK in the paper and look less like a setup because it wasn't perfect."

Kenneth Tanaka: "Anecdotes: I have the wonderful privilege of often seeing some of the most renowned photographic prints in public and private collections, from Fox-Talbot to Burtynsky and Gursky. I doubt that half of them would pass muster as 'sharp' to an amateur photo forum crowd. A few years ago a major American museum photo collection deaccessioned a large Berenice Abbott print. To my eye it was lovely. But amidst the museum's many other Abbott prints this one, which was printed later, was a bit too good. Specifically, it was a bit too sharp and snappy to be representative of Abbott's body of work. It was clearly a later interpretation of the work."

David L.: "I have observed that when one attribute is emphasized obsessively and singularly, that is all that one ends up with. Other qualities are rejected, and lost. Thus making the end result a disappointment at best, a failure at worst."

Dennis Mook: "I achieved a proper perspective (for me) after visiting many museum exhibits and looking at original prints of some of the most iconic photographs made in the 20th century. Whether made by Cartier-Bresson, W. Eugene Smith, Steiglitz, or many of the Farm Security Aministration photographers, many of the images are not what we would call 'sharp' today. In fact, they look softer that what could be made from the least expensive lenses made today. It became obvious to me that the content and meaning of a photograph transcends technique and is much more important that technical excellence."

Rob: "On the subject of sharpness, I like to borrow a quote from Chico Marx: 'Enough is enough, and too much is too much.' For some images, a high level of sharpness adds a sense of realism and presence. But excessive sharpness calls attention to itself and detracts from the image. I also think that we, as photographers and viewers of photographs, are developing a new aesthetic sensibility in which hyperreality (and I don't limit this to HDR) is an accepted style. Whether it will have staying power is yet to be determined."