Which artists would you think might be useful for photographers to know and study?

That was a question I came up with a few days ago, thinking of topics to write about. Trouble is, my list kind of stalled at...four. I was a little shocked that a cascade of names didn't drown my brain. The first three that I thought of immediately were Edward Hopper, Raphael, and Vermeer.

Then I thought of Caravaggio—Mr. Chiaroscuro—and that seems obvious, although I never liked him all that much. His paintings seem violent to me. When I was young I had this persistent sense that I could glean the artist's personality from their art, and when I didn't like what I sensed of the personality, I tended not to like or trust the work.

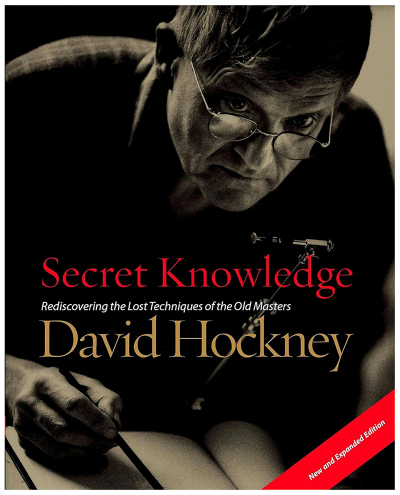

If ever a cover should not have a red banner across the

If ever a cover should not have a red banner across the

corner, it's this one.

After those three I started to run into one peculiar problem. My high school classmate Caroline's daughter, whose name I don't know, was a prolific drawer as a child. When her mother suggested she copy something, when the daughter was nine, she refused, saying, "never go from flat." I love that.

That is, when you're drawing, look at the three-dimensional real world and don't copy something that's already been reduced down into two dimensions by someone else or by some other means. This is a sensitive point with me, because I have a sense when I look at art of all kinds whether "there's a photograph behind it," meaning, the artists is painting or drawing from a photograph. With some art it's obvious, and with some it's almost like a faint shadow and I'm not sure of it. But I tend to like art better when it doesn't have that shadow of a photograph behind it.

It's a bit odd that Hopper is photographic in his vision, yet there isn't that shadow there. And sure enough, Hopper didn't "go from flat." He looked at the real thing and made sketches (many of them) and took written notes. So he might have been a painter who was influenced by photography, but he wasn't one who used photographs to paint from.

Even Vermeer, who died 164 years before the invention of the Daguerreotype was announced, might have been using the lens image as an aid for his painting, according to the (must-see) movie Tim's Vermeer.

Edgar Degas, Race Horses, 1883–85

Edgar Degas, Race Horses, 1883–85

The problem I ran into was that many latter-day and recent representational artists do have that shadow behind their work. Winslow Homer does; Eakins does, to my eye, although I don't hold it against him—I used to say that Eakins was actually a multimedia artist whose final works happened to be rendered as paintings. (Kind of half a joke, like a lot of my opinions about art.) It's easier to forgive artists who worked closer to the inception of photography; when Degas used photographic cropping in paintings, it was radical and new. A friend tells me that Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera is actually a very interesting book for us photographers, regardless of whether you like Rockwell. I love Jordan Casteel, but would someone look at her work purely to inform their photography? It seems odd to suggest that photographers should study artists to improve their photography when the artist might have used photographs to paint from in the first place.

Maybe what I really should do, rather than to compile such a list as I'm proposing, would be to read Secret Knowledge by David Hockney, which I'm rather shocked to find out is from 2006. (I still think of it as "recent.") It's about that very subject: artists who mediate their vision through or with the lens image vs. those who paint from direct observations of three dimensions, from imagination, or abstractly.

The book has always been a little too expensive for me, and I'm flat out of room for more books, sadly. (Half my reference books that I need for this job are already inaccessible in boxes in the attic of the barn. I'm shocked to discover just now (from Amazon's records) that I actually own Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera. It's in a box somewhere and I can't get to it, and out of sight, out of mind. You know what they say: oh well.)

I do tend to forgive artists who were also photographers, which includes Eakins. I have The Photographs of Thomas Eakins somewhere. And it includes the marvelous artist/photographer Saul Leiter whose photography work I cannot get enough of. And David Hockney himself.

Maybe one of my resolutions for 2024 should be to get Secret Knowledge from the library!

Mike

Original contents copyright 2023 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. (To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below or on the title of this post.)

Featured Comments from:

robert e: "I'm going to sort of sidestep the question and suggest studying the artists that move you (whether positively or negatively); just do it deliberately, i.e., with the goal of learning something applicable to photographs.

"Why? First, I think photographers can learn something from most any flat art, including abstracts. Second, there's a lot of art and your time is limited, so you might as well focus on the stuff that resonates personally, that you want to spend more time with anyway. And third, you might learn something about yourself, too."

David Dyer-Bennet: "My mental model is that the thing I could particularly learn about from non-photographic visual artists is composition. (I can of course also learn about that from photographers.) Not to say there aren't other things to learn; there clearly are, particularly if you start including retouching and restoration in 'photography' (because then lots of painting techniques or at least the understanding behind them become relevant).

"('Cropping' is another area where there should be plenty to learn; it's tightly related to composition, too.)

"And, for composition, whether I approve of their techniques or even of their results doesn't really matter, does it? If an image is widely thought to be first-rate, the composition must be at least 'okay,' and is very probably considerably better than that, right? So my looking to figure out how that works has reasonable chances of being enlightening? There's a certain feeling of superiority to be had from thinking you've learned from art you don't like, anyway :-) .

"I've been collecting examples and trying to make time to study them, off and on, for over a decade now I guess. Possibly I might even have learned some things."

Roger Bradbury: "Perhaps you should get rid of that funny looking table in the middle of the 'pool' shed, and fill the space with book shelves.... ;-) "

Mike replies: Part of the original plan: low bookshelves around the edges that cues would clear the top of. Alas, it's not big enough. The room on the floor is needed for footing. The pool shed is big enough, but barely.

A library is actually a perfect room for a pool table. Shelves on all the walls, pool table in the middle. But the room has to be big enough. Take a look at the basement this house in the town I'm thinking of moving to. Very few small houses have any space that is truly big enough for a full size pool table. You need about 19x15 feet clear of any impediments. It's rare to find. I would deal with the less than ideal kitchen, which is probably what's keeping that house from selling.

Oops, am I talking about pool again? I'm not supposed to do that!

Bob Keefer: "I'm going to sidestep the question slightly and suggest a different way for photographers to learn from the classical art world. When people ask me what's the best class to take on photography, I recommend they sign up for a good drawing class. Learning to draw what's in front of you from a decent instructor develops your ability to see the world carefully and accurately, to see what is actually there as opposed to what you expect to see. You also learn about composition and tonal structure of images. Drawing doesn't require talent—only regular practice—and it can deeply change your view of the world and of art."

Len Salem: "Mischievous me suggests that any book by or about any artist you like is worth studying if your intention as a photographer is to express yourself and how you feel about things. Because what, as photographers, many of us need to think about is our intention in making images. Getting to grips with the thought processes of an artist might be valuable help for understanding this. Learning the technique(s) necessary to express that intention is a separate study, and possibly one about which it is easier to become informed or recommend resources."

Hank: "I ran into a Bonnard exhibition during one of my travels a few years back—I think it was at the Tate—and I was struck at how 'photographic' his paintings were. A little research later showed he was a keen amateur photographer."

Mike replies: One of my favorite books is a book of Bonnard's photography. They are not "good," nor do they look at all like my own photographs, but for some reason they just grab me right at base level. Kind of like Howe Gelb's music. Thanks for mentioning him!

Jim R: "When working in color I tend to think of Maxfield Parrish when taking landscape photos after sunset, and William Turner and Hudson School of Art painters when there's water in a scene."

John: "Picasso was supposedly challenged about his distorted representation of an individual—likely his latest mistress. Picasso then asked his interlocutor whether he was married, and if so, did he perhaps have a photograph of her? Out came a wallet and a small snap handed over. 'She’s very beautiful. Such a shame she’s so small, flat, and grey.'

"To Adam Isler’s list of painters, I would add Durer, especially his Great Piece of Turf (Das große Rasenstück); and, George de La Tour, 'The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds,' in the Louvre collections."

Tom Burke: "It would have to be 'realistic' painters, I think. So, for example, still life and genre paintings from the Dutch Golden Age, would inform photographers of similar subjects. And portrait paintings, surely—again, Dutch masters, as well as artists such as Lawrence and Gainsborough. And then there's Joseph Wright 'of Derby.' If you want chiaroscuro without the violence, e.g. 'A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery'. It would be challenging to tackle a subject with that much dynamic range with a digital camera and try control it...."

I think any of the Hudson River School artists are worth studying, just for learning how to use light in composition.

Also, Monet, for the same regarding color.

Posted by: Aakin | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 12:19 PM

We have just been looking at this (and the Hockney video) in my photography MFA. From my class notes, I would suggest off the top of my head, Goya, Manet, Bruegel the elder, Holbein, and Seurat. Each has something to say not just in terms of the content of their paintings but also visual qualities and composition from which a photographer can learn.

Posted by: Adam Isler | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 01:19 PM

I'm voting for Monet, just because I think the changing light we see in his repeated paintings of the same subject can be instructive to us. All that not stepping in the same river twice, so to speak.

Posted by: Chris Bertram | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 01:53 PM

Velazquez, especially Las Meninas, and John Singer Sargent come to mind. I think looking at famous paintings of people can be deceptive in the sense that what makes them so interesting are the painter things; such as a riot of tiny colors and brush strokes in the skin tones, shadows and highlights that defy physics. You don’t hear many people talking about Andrew Wyeth, but some of his portraits are certainly worth a look. For me, personally, I find my inspiration informed by non representational art, Rothko paintings, literature, music, etc.

Posted by: Kirk Decker | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 02:25 PM

Hockney counts as a major (albeit over a short space of time) photographer. His collages: he called "joiners." Not everyone (I believe) thinks of them as photographs, but I think they most definitely are, and they bring (as he says) the sense of a 3rd dimension. I believe he means time--but I cannot find his book at the moment.

For me they bring a sense of volume (more than time)--but I am using the technique for inanimate subjects. It is a technique I used w/ film where I got back 2 sets of borderless 4x6 prints and then "joined" them into collages.

I almost wish I didn't do digital, as that process is not something I do now. (Of course I could do it now, but the more accidental/spur of the moment aspect, as I first looked at the prints, was more spontaneous.) But I had decided to go back to mostly film for outdoors work, and thus will make joiners again.

Posted by: Daniel Speyer | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 02:27 PM

It seems that Picasso was often inspired by the photographs on African postcards.

Posted by: Herman Krieger | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 02:53 PM

Degas was a photo enthusiast, and learned a lot from them, like how to express motion through cropping. Artists like Richard Estes and Chuck Close worked extensively with photos -- Close took relatively small photos and with paint, used a kind of abstraction that blew them up to huge sizes that resolve into realism when you stand well back...The Photo-Realists like Estes didn't just reproduce photos, though. They edited them, and took stuff out and put stuff in, though the final result was photo-realistic. Kind of like AI photos now...You couldn't know what was real and what wasn't by looking at their paintings.

Posted by: John Camp | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 04:12 PM

There was a wonderful exhibition at the Tate Modern in London recently that addressed the relationship between art and photography. Each art form has influenced the other. There were works by Picasso and Hockney and many others. It might still be running. I have Hockneys Secret Knowledge. Its a real eye opener. Highly recommended.

Posted by: Bob Johnston | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 06:14 PM

For color and composition my favorite painters are Rembrandt, Vermeer and Andrew Wyeth. Pity I'm a very poor photographer of color ...

Posted by: William Lewis | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 06:50 PM

Mike said...

"If ever a cover should not have a red banner across the

corner, it's this one."

I agree!

And what a great picture it is if you crop it just under the 'red' title. I am kinda partial to 'Landscape' format portraits that are tight.

Posted by: JTK | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 07:25 PM

“… to read Secret Knowledge by David Hockney, which I'm rather shocked to find out is from 2006. (I still think of it as "recent.")”

To which my immediate reaction was “Huh? 2006 *is* recent! Oh wait…” #timefail

Posted by: Ed Hawco | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 08:43 PM

Thematically, Rockwell did something interesting in that he painted people at work. It's not something I see much. While I was still spending my days in cubicle farms I often wondered how I could make interesting photographs of people sitting at desks looking at screens but never did anything about it. It's probably too late for me now as I'm retired and most employers are suspicious of strangers wandering the aisles taking pictures of work places.

[Lee Friedlander is one exception that comes to mind, although his pictures were, curiously, quite stylized, in a way.

I used to be quite interested that nobody took pictures of ordinary workaday places like mechanic's garages, supermarkets, DMVs, etc. But many of those places won't let you photograph, so you have to do it on the sly. Not something that's very comfortable. But it makes such scenes under-documented. --Mike]

Posted by: Robert Roaldi | Thursday, 23 November 2023 at 09:21 PM

Oh my!

I've touted Tim's Vermeer here at least twice.

In this context it's really must see, as Tim Jenison explicitly launches from Secret Knowledge in his search for Vermeer's technique.

Hockney refers to another aspect of art production at that time, "The popular conception of an artist is of a heroic individual, like, say, Cezanne or van Gogh, struggling, alone, to represent the world in a new and vivid way. The medieval or Renaissance artist was not like that. A better analogy would be CNN or a Hollywood film studio. Artists had large workshops, with a hierarchy of jobs. They would attract the talented, and the best would be quickly promoted. They were producing the only images around. The Master was part of the powerful social elite. Images spoke and images had power. They still do.

As it happens, I went to an exhibition yesterday:

Botticelli Drawings is the first exhibition ever dedicated to the drawings of Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli (ca. 1445 – 1510). Exploring the foundational role drawing played in Botticelli’s work, the exhibition traces his artistic journey, from studying under maestro Fra Filippo Lippi (c. 1406 – 1469) to leading his own workshop in Florence.

Among many things I observed and learned, is the individual hand of the master. Although many aspects of many paintings were done by apprentices, it's not often hard to recognize which is which.

A good example is Virgin and Child With Saint John the Baptist and Six Singing Angels

As it (again) happens, shortly after I contemplated this painting, the guide of a tour said what I'd been thinking, that most experts believed that the faces, hands and perhaps upper bodies were painted by Botticelli himself, and the rest by others.

There are also many examples of preliminary drawings to work out the details of a planned composition. Apparently, a lot of painting done by apprentices was closely based on instructional drawings.

IR scans reveal a lot of under drawing. It's possible that the master drew in outlines of parts and others filled them in.

Might some of the prelims have been done using an optical device, then copied by eye onto the final product? If so, a clever way to maintain accuracy to subject while allowing the eye of the artist limn the final image ( and avoiding Hockney's dreaded obvious optics.)

Posted by: Moose | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 12:40 AM

Some artists expressly explore this dichotomy. Take, for instance, the artist Vija Celmins, whose meticulous drawings are rather rare, as she produces relatively little. I am thinking in particular of her all-over pencil drawings of seascapes, which are technical marvels. One is enticed to think that these drawings are an invitation to the romantic sublime, depicting vast nature in all is wonder. On further rumination, however, one begins to get the suspicion of which you speak — that she “is working from flat.” That is in fact true but not obvious. But for those trying to resolve the dilemma there is rather a strong hint in certain of Celmins' seascapes (including the one that hangs in the room where I type this comment). In those, there is a perfect white X crisscrossing the entire picture plane. To say the X is subtle is an understatement. Even knowing it is there, I can only see it with my nose a few inches from the paper and, even then, it takes a few minutes to find it (and may well evanesce a moment later). It is a white X in the same way, if you will, that Frank Stella painted white lines on a black ground in his famous Black Paintings of 1958 - 1960, which is to say not at all. While most apprehend these Stellas as showing white lines over a black ground, in fact, those lines are simply parts of the canvas that are not painted black (and on examination, these supposed examples the epitome of hard-edged abstraction reveal that, because these thin white lines simply show the unpainted ground of the canvas, the lines are in fact rather delicately feathered). That is exactly what Celmins' Xs are -- very thin parts of the paper on which she did not draw (not drew but then erased). On a highly detailed but subtle gray all-over pencil drawing of a seascape this is, as I say, almost impossible to see. But the entire construction of the drawing, as I see it, is about this push-pull of assessing the picture as a drawing from nature versus from a photograph.

Posted by: CalvinAmari | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 01:15 AM

Sheeler is one of my favorite artists who explored across media, as discussed here..

https://www.nga.gov/features/slideshows/charles-sheeler.html#slide_1

So did Ralston Crawford and Brancusi.

Posted by: Jeff | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 09:32 AM

The basement of that house at the link would be about big enough, then. The small windows would keep the fading of prints and book spines to a minimum, too.

I can't quite work out the layout, but if that bit of the basement with the exposed floor joists above is below the kitchen, rearranging the kitchen would be straightforward. It looks like the cooker was just shoved into the most convenient spot; it needs a work surface on at least one side and that's a terrible place to put a microwave.

Posted by: Roger Bradbury | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 10:03 AM

As a literature major, I know there is writing I really enjoyed reading for a class, struggling with the text, having good discussions, writing that I would likely never read on my own for "personal pleasure." I suspect the same with the visual arts and music, though I've never studied either formally. In my ideal imagined world, we would have more time to participate in group learning and art appreciation beyond those few dear years in college.

My dad heavily stressed that we should never "copy" when drawing, which of course caused me to rebel. In high school and college I was good at both drawing "from flat" and from the world. And you can of course mix the two, like a photoshop of the mind. Art is art.

Posted by: John Krumm | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 10:56 AM

Right around the time I started actively taking digital photos, I dated a visual artist off and on. Her large paintings were abstracts of real things, often intricately patterned. Though not landscapes, they were laid out like Japanese prints of landscapes, and it changed the way I saw photos out on my solo hikes. She also had a huge book of Edward Curtis photographs, so dramatically composed and painterly, which influenced her layouts, too. We would travel to see galleries and museums, LA, Chicago, SF, Seattle, NY, solely to see a lot of art, and I was visually alive in and after those years.

It wasn’t necessarily that my photos were directly from what I saw in paintings, more that my eye was very awake. But then I think I thought I was seeing elements and fragments and overall scenes of all this art I had quickly digested while I was in this fertile shooting period. When I was taking photos, I guess I felt I was starting to “speak” in a shared visual language with all these artists I was being exposed to. (Mirroring another commenter, I had a similar awakening in how I parsed the world after two successive figure drawing classes, yeah.)

Don’t get me wrong: my photos have been ok but not that great. I can’t compete with the art I saw. But it was fun to feel imbued with these visions while out photographing. My pictures then were better than they are now, and the effort felt more meaningful.

Posted by: xf mj | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 01:55 PM

I started off as an ardent landscape photographer, and have since morphed into a painter, oil on canvas.

It has been a weird journey. My landscape photography was originally driven by the Ansel Adams books, and by the opulent color work of Christoper Burkett and Charlie Cramer. I did start painting from photographs, and they're still part of my practice. But I also do a lot of plein air (on-site) painting from life. I have no doubt that the composition and design of my paintings owes a lot to how I see photographs. My default field of view for paintings I have found corresponds to ~100 mm focal length in 35 mm format.

There are some very prominent current landscape painters who proudly eschew photography, including Joseph McGurl and Joe Paquet. And yet, their paintings very clearly reference photographic composition and the visual style of photographs! There's no escaping it; even if you intentionally paint in a non-photographic, non-representational manner, you're still responding to photography.

I've read Hockney's Secret Knowledge. I happen to believe he's wrong; surely some old masters were using something like a camera obscura, but to my eye most were not.

Finally, there are plenty of painters one can study to inform photographic composition. But pick your poison; if you love wide, spacious vistas and endless skies? Jacob Van Ruisdael. Dramatic waves crashing on the shore? William Trost Richards and Frederick Judd Waugh. Lofty mountains? Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt, or Edgar Payne.

Posted by: Geoff Wittig | Friday, 24 November 2023 at 06:48 PM

Late here. There are so many excellent suggestions regarding artists from other media and times to study.

My own recommendation is to second Bob Keefer‘s excellent suggestion for photographers to learn drawing. If you’ve never had any formal collegiate art training you’ll likely discover the skills you’ve been missing. Slowing-down to practice an additive medium forces you to learn to SEE figure-ground, proportions, gesture, perspective. Instead of thinking of “composition” you learn to think in terms of constitution. Get s sketch book and some good artists pencils, etc. and spend a year making at least one sketch a day. They may not be very good and you need not show them to anyone. But I guarantee your photography will noticeably improves regardless of your age, or your money back.

Posted by: Kenneth Tanaka | Saturday, 25 November 2023 at 10:08 AM

Recently visited the Sorolla exhibit at the Meadows Museum in Dallas, TX, so I'd add him to your list.

https://meadowsmuseumdallas.org/exhibitions/sorolla-in-american-collections/

Very much about the light.

Posted by: Merle | Monday, 27 November 2023 at 09:57 PM