A most interesting photographic book reissued and restored.

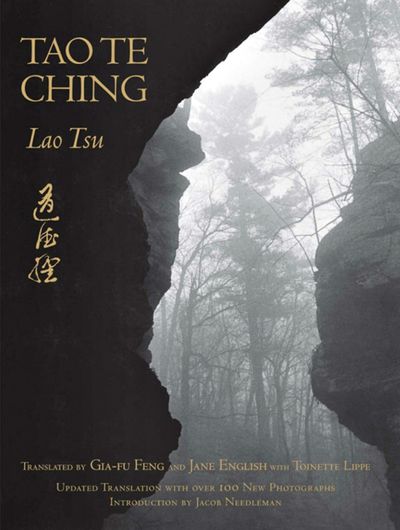

The Vintage illustrated bilingual edition of The Tao Te Ching (sometimes translated as "the way and its power" [Waley] or "the classic of the path of virtue" or simply "the book of the way") was one of the great populist-spiritual bestsellers of the 1970s in America. It featured the Chinese text in calligraphy by Gia-Fu Feng with an English translation by him (more about that in a moment) and was decorated throughout by black-and-white nature photographs by Jane English, who assisted with the translation.

The Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing in Pinyin romanization) is one of the foundational works of Chinese philosophy and one of the most frequently translated books extant; it consists of 81 brief, elliptical, poetic, aphoristic verses that define a mode of approach to life and to enlightened governing. If Confucianism is the objective/extroverted/strict/public-duty side of ancient Chinese philosophy, philosophical Taoism is its subjective/introverted/live-and-let-live/interior-life counterpart. There are many classics in the sprawling Taoist tradition (Taoism is both a philosophy and a religion, and the two seem little related), but the ancient and mysterious Tao Te Ching is bedrock.

The text dates from six centuries before Christ. According to legend it was written by Lao Tzu (Laozi in Pinyin), which means "old boy" or "old one," as a last commentary on life as he went into permanent exile—a former advisor to the Emperor, he was exhorted to write down his philosophy by a frontier guard as he departed society. More likely is that it is folk philosophy, a collection of related passages (some of which probably had a common author or source) that took shape and form over time, much like a folk song being transmitted from person to person, place to place, and generation to generation, repeated again and again.

It's worthwhile to note that Alan Watts thought this view an error, the result of a modern fashion for skepticism about the reality of religious leaders as individuals. Watts wanted to leave open the possibility of an actual single author.

A perfect translation is not possible. The text is mysterious and enigmatic in the original, veiled by its ancient origins and its essential inscrutability before one even arrives at the problem of bridging the archaic Chinese language to modern English or crossing the divide of the many disparities in the respective cultures. The book even begins with the famous phrase "The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao"—and the Tao that can be translated is not the definitive Tao, either. (By the way, "Tao," which means "way" or "path," is pronounced about like dow, as in Dow Jones.) Many translators have made the text "their own," imposing their own interpretation or even their own philosophy on their wordings; some translations take a literalistic approach, some a scholarly/historical approach, some an impressionistic, communicative intent. The Tao Te Ching has even had its share of "translators" who do not speak or understand Chinese! They work from other translations or from literal transliterations.

That was not the case with the famous Vintage book. Gia-Fu Feng was not "artfully" fluent in English at the time, but he studied the text very deeply and respectfully; his wife, photographer (and particle physicist) Jane English helped make his words idiomatic. The idea of combining Chinese calligraphy, photographs, and English translation was theirs. But the original manuscript text, while thoughtful, was rough. The task of editing it fell, very fortuitously, to English-born Toinette Lippe, then an acquisitions editor at Alfred A. Knopf. The project came to her fortuitously and she believed in it—becoming its "midwife" to use her word. Toinette was well suited in temperament and intelligence to edit the book, and worked patiently with Gia-Fu Feng to mold the English text. She did so by comparing a dozen existing translations sentence by sentence and then trying to understand what Gia-Fu and Jane's interpretation was, helping to put that into felicitous English using words that didn't echo other translations.

The result soared. Although not persnickety or strictly scholarly (which can lead to layered, shaded meanings but plodding, earthbound English), translators and editor collaborated to create a version that cut to the essence of the ancient work in a way that spoke plainly and directly to modern English-speaking Westerners. Given that the late '60s and early '70s were a time when interest in Eastern thought and religion was flowering in America, it was as if every element came together in the best possible way: over the years, the book has never been out of print and has sold well over a million copies, astonishing for a single translation of an ancient Chinese classic with hundreds of translations. (If you can count just the translations currently available on Amazon, you are more patient than I.) The famous book changed the lives of the three collaborators...and, it's no exaggeration to say, of many readers as well.

I liked to tell the "hidden story" of Toinette's involvement for many years. The new (2011) edition of the book makes that unnecessary—it has a great new foreword that details the story of the book's creation, and that shares the credit all around generously and accurately. The new "front matter" alone is worth the price of a new copy.

I think the newly modified translation is better than the now-"classical" original as well. Gia-Fu Feng died in 1985 after a distinguished career, but Toinette and Jane worked together, and in consultation with the eminent philosopher and Sinologist Jacob Needleman, to refine the translation still more—for one thing getting rid of the sexist "he" and "his" (ancient Chinese doesn't use pronouns) and replacing "the Sage" (which can be read as singular and exceptional) with "the Wise" (more inclusive and encompassing). Jane English, who created a Tao calendar for years for her fans using newer photographs, replaced almost half the photographs in the book—about 100—with newer work.

The Tao Te Ching has been translated into English more times than any other book except the Holy Christian Bible. There are other translations that are indispensible (at one time I owned more than 30 of them, along with at least as many books of commentary and scholarship on the text—speaking, as we were recently, of personal touchstones), but for readers whose native tongue is English, the Feng/English/Lippe translation is the first to have and the one I recommend most often. A must for everyone's bookcase.

Oh, and there is a text-only edition—but get the one with the photographs

! Or don't I need to say that here?

(Here it is at Amazon U.K. , and at The Book Depository. Links to Amazon Germany and Canada can be found here.)

Mike

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Dave: "There is a well-worn copy of the original resting on my living room bookshelf. I leaf through it once every couple weeks. Of all my 'photography' books, this version of the Tao Te Ching provides the most inspiration. The photos are simple yet beautiful and they match the text perfectly. The book is a triumph of minimalist graphic design. It outshines the expensive hardbacks that surround it on my shelf. And, the lessons of The Tao are life-changing. What more could someone want in a coffee table book? I'm looking forward to this updated version."

Dennis Ng: "Zi is definite not 'boy' in this context and one hundred percent sure unlike those other arguments you may try. If you have to use this way then Confucius is a 'hole boy'...etc. It is more like 'master,' 'teacher,' 'respected name' as no one calling themselves zi except those old people around that time. 'Old one'...where you get that from? :-) A simple translation may be 'the old guy' if you have to remain colloquial."

Eh. I disagree. Waley's "The Way and Its Power" is far more authoritative in every way, and reads quite well.

One of the problems with ancient Chinese texts today is that people familiar with modern Chinese, including native Chinese speakers, think they can read and understand ancient works. What they often don't realize is that some of the words (ideograms) in these texts no longer mean what they did 2000+ years ago. The introductory essay to Richard Rutt's superb translation of the Zhouyi (the earliest form of the I Ching, without the later commentaries) discusses this issue in detail as it applies to that work, and the same difficulties apply to the Daodejing.

[I agree that Waley is essential. I might not recommend it as the first version to read for someone unfamiliar with the work. --Mike]

Posted by: Craig | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 07:06 PM

Thanks a lot for posting!

I tried hard to find this book just a month ago - but I could not find the version with the photos. It really is a very good combination of the old text, calligraphy and photos. Love it.. Very inspiring indeed!

By the way; thank you for a great site.

Posted by: Jens | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 07:16 PM

Certainly one of the great combinations of translation and presentation of this classic.

How is the photo reproduction quality? Our 1972 original has only so-so image quality. Hard to see buying another one unles it is visually more pleasing.

Their Chuang Tsu, Inner Chapters is excellent, too.

Moose

Posted by: Moose | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 07:39 PM

My understanding is that the oldest evidence for the Daodejing in something like its current form comes through the Mawangdui texts, which date to the early second century BCE, but have diverged enough from each other to suggest a nontrivially earlier origin, and that the earliest text that recognizably corresponds to a substantial part of the Daodejing is found in the Guodian slips, dated around 300 BCE. I don't believe there's really solid evidence to put its origin (to the extent that it has a precise origin point) "six centuries before Christ", although this impression on my part is based on vague recollections and hasty internet research.

Tradition places Laozi in the sixth century BCE, but, as you note, it's not really clear that he was a historical figure, and dating him to this time period seems suspiciously like a move intended to make him a contemporary of Confucius.

In any case, it's clearly a pretty old book.

[I'm not a specialist and I'm not up on the current research, but your understanding is pretty much mine too--I've always felt intuitively that Taoism was probably a reaction to Confucianism and probably came later, so the traditional assignation of Lao Tzu as a contemporary of Confucius was probably defensive at some point--"our guy is as old as your guy" kind of thing. The 300 BCE estimate is one I've heard as well. The latest book I have on the Ma-wang-tui texts is dated 1989.... --Mike]

Posted by: B. R. George | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 07:49 PM

I have the original, given to me by a special friend. For me, the stilted, clumsy translation is what makes the first edition so special; its child-like English manages to somehow articulate the 'inarticulable' that is the mystery of being and knowing. I never liked the ancient Chinese text, whose compactness and passive tone strike me as too perfect, too knowing, too... smug -- which contradicts the text, or at least the spirit of the text. English's quiet, impenetrable images otoh are just perfect. Can this new version be better? Guess I'll have to buy one and see for myself.

Posted by: A.C. | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 08:10 PM

I read it along time ago... don't remember which version. Your review convinced me to buy again(through your link of course).... and I tacked on 5 rolls of 120mm TMax 100. No more drinking while reading TOP.... not my first impulse buy here....

Posted by: Tim Fitzwater | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 08:33 PM

I still have my original 1972 edition, along with Chuang Tsu - Inner Chapters, by the same authors. Both highly recommended.

Posted by: lynnb | Thursday, 06 February 2014 at 09:32 PM

Ahhh, yes. I have that book. A few years ago, I took a Tao Te Ching workshop from Ken Cohen, and the Gia-Fu Feng translation was Ken's favorite translation as well. We compared a lot of translations in that class, and this one was the most poetic, while still sticking closely to the original text. And pictures!

One interesting tidbit I learned in that class...the word Tao is used three hundred and some times in the text, and each time the word had a different meaning. This Tao and that Tao were all different Taos...

Posted by: Ann | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 12:10 AM

The first translation of the Tao Te Ching that I ever read was by Stephen Mitchell and I was instantly hooked. Soon after, I became aware that there were many more translations out there but most of them that I read through seemed disappointing in one way or another. Although I will always love the simplicity and modern language of Mitchell's translation, I am still eager to read other recommended translations. I had not yet heard of the Feng/English/Lippe version until you posted this today. Thank you for bringing it to my attention.

Posted by: Lee | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 01:14 AM

30 different versions? No wonder you are so wise... O TOP Sage ;)

Posted by: Chan | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 01:21 AM

Lovely book design, I like the photographs accompanying the text!

I have several copies of various English translations, the one I like the best is a bi-lingual version with commentaries by Red Pine aka Bill Porter

Posted by: Peter Szawlowski | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 09:04 AM

Lesson learned. Book purchased immediately instead of hemming and hawing around (e.g. Pentti, Abelardo Morrell) and then not being able to get a good deal.

THIS is the Tao of buying books Mike recommends . . . .

Posted by: GRJ | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 02:50 PM

Have to also recommend the work of Victor Mair at the University of Pennsylvania.

Posted by: Kirk Fisher | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 02:51 PM

Never realized that Laozi is well read outside China. The Dao classics, including Daodejing and Zhuangzi, are hard to understand for me, and as a Chinese I have a fairly good education in ancient Chinese text. The difficulty is in the meaning. They must be difficult to translate to other languages too, just like old style Chinese poem. Hard to preserve the "taste".

About the meaning of Zi in this context: I was thinking to clarify it last night but today I see Dennis Ng is right, So I will shut up. Laozi is still used by Chinese man sometime today to refer to himself, as "I", but usually in a playful way or when he is angry.

Posted by: wchen | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 03:36 PM

Went to my bookshelf to see what translation I owned. Yup, the 1972 Feng. So flows the Tao.

Posted by: Jeff Hohner | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 05:39 PM

Thanks for pointing this out. It's a beautiful edition of one of my favorite books, and a very different translation from the others that I already have. It will take some getting used to after spending so much time with the Philip Ivanhoe translation. But I'm looking forward to it.

Posted by: Adam D. Zolkover | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 08:49 PM

As a calligrapher (http://facebook.com/richardmancalligraphy), Daoist, photographer (http://facebook.com/richardmanphoto), and part time Chinese scholar (mainly in classic martial arts text), doing a project like this is on a short bucket list of things I want to do in the next 10 years.

Posted by: Richard Man | Friday, 07 February 2014 at 08:51 PM

BTW, there is no way that Tao Te Ching is a reaction to Confucianism. Taoism/Daoism, comes from the long line of indigenous shamanic practices (Wu 巫), dated back to the days of the oracle bones.

Posted by: Richard Man | Saturday, 08 February 2014 at 03:05 AM

Studied that in my history lessons. Not much in the way of practical applications.

Posted by: Dan Khong | Saturday, 08 February 2014 at 05:55 AM

Any good novels (written in English) to recommend which might introduce a person to the non-fictional Tao via the character's lives in the fictional story?

Posted by: JH | Tuesday, 11 February 2014 at 04:11 PM