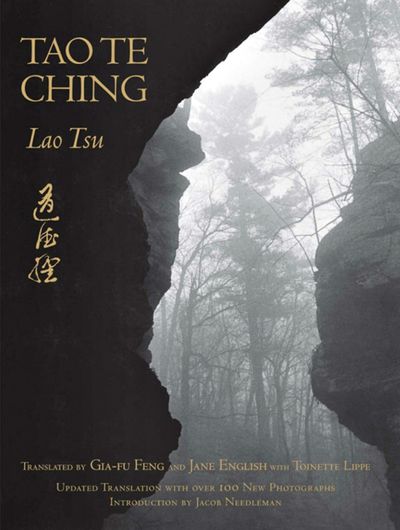

A most interesting photographic book reissued and restored.

The Vintage illustrated bilingual edition of The Tao Te Ching (sometimes translated as "the way and its power" [Waley] or "the classic of the path of virtue" or simply "the book of the way") was one of the great populist-spiritual bestsellers of the 1970s in America. It featured the Chinese text in calligraphy by Gia-Fu Feng with an English translation by him (more about that in a moment) and was decorated throughout by black-and-white nature photographs by Jane English, who assisted with the translation.

The Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing in Pinyin romanization) is one of the foundational works of Chinese philosophy and one of the most frequently translated books extant; it consists of 81 brief, elliptical, poetic, aphoristic verses that define a mode of approach to life and to enlightened governing. If Confucianism is the objective/extroverted/strict/public-duty side of ancient Chinese philosophy, philosophical Taoism is its subjective/introverted/live-and-let-live/interior-life counterpart. There are many classics in the sprawling Taoist tradition (Taoism is both a philosophy and a religion, and the two seem little related), but the ancient and mysterious Tao Te Ching is bedrock.

The text dates from six centuries before Christ. According to legend it was written by Lao Tzu (Laozi in Pinyin), which means "old boy" or "old one," as a last commentary on life as he went into permanent exile—a former advisor to the Emperor, he was exhorted to write down his philosophy by a frontier guard as he departed society. More likely is that it is folk philosophy, a collection of related passages (some of which probably had a common author or source) that took shape and form over time, much like a folk song being transmitted from person to person, place to place, and generation to generation, repeated again and again.

It's worthwhile to note that Alan Watts thought this view an error, the result of a modern fashion for skepticism about the reality of religious leaders as individuals. Watts wanted to leave open the possibility of an actual single author.

A perfect translation is not possible. The text is mysterious and enigmatic in the original, veiled by its ancient origins and its essential inscrutability before one even arrives at the problem of bridging the archaic Chinese language to modern English or crossing the divide of the many disparities in the respective cultures. The book even begins with the famous phrase "The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao"—and the Tao that can be translated is not the definitive Tao, either. (By the way, "Tao," which means "way" or "path," is pronounced about like dow, as in Dow Jones.) Many translators have made the text "their own," imposing their own interpretation or even their own philosophy on their wordings; some translations take a literalistic approach, some a scholarly/historical approach, some an impressionistic, communicative intent. The Tao Te Ching has even had its share of "translators" who do not speak or understand Chinese! They work from other translations or from literal transliterations.

That was not the case with the famous Vintage book. Gia-Fu Feng was not "artfully" fluent in English at the time, but he studied the text very deeply and respectfully; his wife, photographer (and particle physicist) Jane English helped make his words idiomatic. The idea of combining Chinese calligraphy, photographs, and English translation was theirs. But the original manuscript text, while thoughtful, was rough. The task of editing it fell, very fortuitously, to English-born Toinette Lippe, then an acquisitions editor at Alfred A. Knopf. The project came to her fortuitously and she believed in it—becoming its "midwife" to use her word. Toinette was well suited in temperament and intelligence to edit the book, and worked patiently with Gia-Fu Feng to mold the English text. She did so by comparing a dozen existing translations sentence by sentence and then trying to understand what Gia-Fu and Jane's interpretation was, helping to put that into felicitous English using words that didn't echo other translations.

The result soared. Although not persnickety or strictly scholarly (which can lead to layered, shaded meanings but plodding, earthbound English), translators and editor collaborated to create a version that cut to the essence of the ancient work in a way that spoke plainly and directly to modern English-speaking Westerners. Given that the late '60s and early '70s were a time when interest in Eastern thought and religion was flowering in America, it was as if every element came together in the best possible way: over the years, the book has never been out of print and has sold well over a million copies, astonishing for a single translation of an ancient Chinese classic with hundreds of translations. (If you can count just the translations currently available on Amazon, you are more patient than I.) The famous book changed the lives of the three collaborators...and, it's no exaggeration to say, of many readers as well.

I liked to tell the "hidden story" of Toinette's involvement for many years. The new (2011) edition of the book makes that unnecessary—it has a great new foreword that details the story of the book's creation, and that shares the credit all around generously and accurately. The new "front matter" alone is worth the price of a new copy.

I think the newly modified translation is better than the now-"classical" original as well. Gia-Fu Feng died in 1985 after a distinguished career, but Toinette and Jane worked together, and in consultation with the eminent philosopher and Sinologist Jacob Needleman, to refine the translation still more—for one thing getting rid of the sexist "he" and "his" (ancient Chinese doesn't use pronouns) and replacing "the Sage" (which can be read as singular and exceptional) with "the Wise" (more inclusive and encompassing). Jane English, who created a Tao calendar for years for her fans using newer photographs, replaced almost half the photographs in the book—about 100—with newer work.

The Tao Te Ching has been translated into English more times than any other book except the Holy Christian Bible. There are other translations that are indispensible (at one time I owned more than 30 of them, along with at least as many books of commentary and scholarship on the text—speaking, as we were recently, of personal touchstones), but for readers whose native tongue is English, the Feng/English/Lippe translation is the first to have and the one I recommend most often. A must for everyone's bookcase.

Oh, and there is a text-only edition—but get the one with the photographs

! Or don't I need to say that here?

(Here it is at Amazon U.K. , and at The Book Depository. Links to Amazon Germany and Canada can be found here.)

Mike

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Dave: "There is a well-worn copy of the original resting on my living room bookshelf. I leaf through it once every couple weeks. Of all my 'photography' books, this version of the Tao Te Ching provides the most inspiration. The photos are simple yet beautiful and they match the text perfectly. The book is a triumph of minimalist graphic design. It outshines the expensive hardbacks that surround it on my shelf. And, the lessons of The Tao are life-changing. What more could someone want in a coffee table book? I'm looking forward to this updated version."

Dennis Ng: "Zi is definite not 'boy' in this context and one hundred percent sure unlike those other arguments you may try. If you have to use this way then Confucius is a 'hole boy'...etc. It is more like 'master,' 'teacher,' 'respected name' as no one calling themselves zi except those old people around that time. 'Old one'...where you get that from? :-) A simple translation may be 'the old guy' if you have to remain colloquial."