By Geoff Wittig

I find it fascinating that very specific films or imaging technologies have so narrowly defined the "look" of color photography over the years.

The recent eulogy for Kodachrome here at T.O.P., and the beautiful examples of work done with this film, got me thinking a little "meta" on the subject of imaging technology. Not to get all McLuhan about it, but the æsthetic and perceptual characteristics of a particular film tend to constrain or channel the way we see, especially in color. Kodachrome is the greatest example of this, because it dominated color photography and reproduction for decades. Once color offset printing became affordable, photography in the book and magazine publishing industries was largely built on this specific transparency film. Photographers who learned how to get great results with Kodachrome essentially created the visual "look" of the period circa 1960–1980.

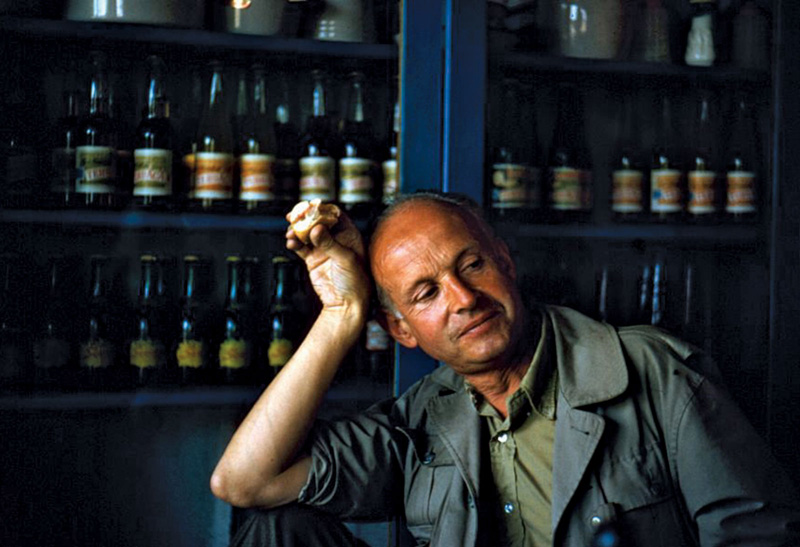

Henri Cartier-Bresson by Ernst Haas, on Kodachrome.

Henri Cartier-Bresson by Ernst Haas, on Kodachrome.

Study any color photo book from this era. Almost invariably you'll see the Kodachrome æsthetic: rich warm tones and relatively subdued greens, with deep shadows as an artifact of the slight underexposure required to get decent color saturation. As long as you kept the highlights under control, you'd reliably get that nice palette: lovely blue skies, subtle cool greens, and burnished warm colors with impact out of proportion to their size in the frame. To me it sometimes seemed like looking at the world through a glass of Scotch. For folks my age, learning color photography meant learning to see the world like K64 did. (I don't mean to ignore color print film; I'm aware that the sales volume of C-41 films dwarfed all the chromes combined. But their frequently abysmal color permanence combined with the vagaries of automated printing and the dominance of transparency film in publishing conspired to make them less relevant.)

Forest Drive, Great Otway National Park. Photo by Glenn Guy using a Leica R8, 90mm Summicron, and Fuji Velvia 100F film.

Forest Drive, Great Otway National Park. Photo by Glenn Guy using a Leica R8, 90mm Summicron, and Fuji Velvia 100F film.

E-6 films began to erode Kodachrome's market share ever faster from about 1980, and in 1990 the Velvia steamroller arrived. At least for nature and landscape photography, the prevailing color æsthetic changed dramatically. The hypersaturated, brash, neon colors of Velvia and its imitators came to be the perceptual 'filter' through which people saw the world. It's completely understandable; those luscious glowing transparencies on a lightbox are hypnotizing. But it's also a weirdly distorted, cartoonish vision of the world, one that basically mandates photographing in soft/overcast light or within a few minutes of sunrise/sunset.

In the last decade we've seen another great shift in the way color photography sees the world, with the digital juggernaut. The potential of this technology for greater subtlety and fidelity seems to be losing out, at least in nature/landscape photography, to an irresistable urge to mimic the Velvia æsthetic. I sometimes shudder at the countless over-saturated digital confections published in magazines and coffee-table books. Digital also adds its own quirks, of course. Sharpening halos, plastic textures, shadow noise and empty highlights can be a lot less attractive than organic-looking film grain. There's hope, though. Excellent digital exposure and processing provide a completely different level of quality from a thoughtless default.

And we're no longer chained to the vagaries of a K64 processing plant the size of a small steel mill at the instant of exposure.

Geoff

Geoff Wittig, a "humble country doctor" in New England, is a regular contributor to TOP.

Send this post to a friend

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2010 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

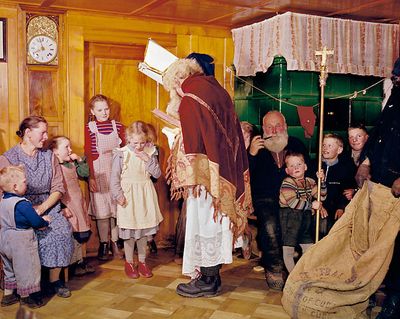

Featured Comment by Adrian: "Keeping with the book-theme of the previous post's comments: Here's a beautiful book with pictures about the life in Swiss countryside in the 1950s. The (Swiss German) commentary in the video on the website claims that the images were taken with Kodak transparency film from 1952 to 1958."

Featured Comment by Keith B.: "The 'Velvia Steamroller' could be said to have actually started with the introduction of Fuji 50(E-6), with its increased color saturation (compared to Kodachrome 25 or Ektachrome 64) and outstanding fine edge detail characteristics, sometime in the early 1980s. Fuji 50 was to be merely a preview of the jacked-up, borderline-false color Velvia which appeared by about 1984. I worked at Bel Air Camera in Westwood Village (L.A.) at the time, and the Fuji rep handed out samples of the first Velvia in 35mm. My Velvia sample rendered white cumulus clouds shot on a clear, sunny day with a magenta cast, so I went back to my preferred distortion of reality, Kodachrome 25."

Featured Comment by Frank P.: "A Kodak Scientist told me that in the early 1950s, color negative film was intended to be the primary photographic medium for professional photographers to use for color lithographic reproduction (i.e. magazines, books, advertising, everything!).

"In the ideal Kodak workflow, the professional photographer would handcraft a carefully adjusted and retouched color print to be shot for color separations. The photographer maintained complete creative control over the look and feel of their images.

"What happened? Clients and color separators wanted chromes. The photographer relinquished the control and craft aspect of making prints for commercial repro and instead togs spent the next 50 years in an inane game of chasing color and attempting to make their transparencies consistent and pleasing...which is why I have a collection of 025 Wratten Gel filters fading away in the basement.

"Transparencies may have been nice to look at but it's a real shame they were so popular. They stifled a lot of the creative options that a good photographer could have used to make more distinctive and individualized art."

Nice little essay, Geoff.

"Color Imaging Constrains How We See"

It certainly can.

As a 95% color shooter, however, my title to this essay would probably be something like: "The Liberating Power of Color Imaging"

My text probably wouldn't be much, if any, different from yours! I agree on all points you've made. But I would have added a second half to the thought excursion by highlighting just how powerful and evocative color photography can be when executed by skilled eyes and hands.

Color provides us with an exponentially larger kit of instruments. The fact that perhaps less than 10% are skilled in using these additional tools is neither surprising nor disturbing. (As you probably know better than I, a shocking percentage of people can't accurately see colors at all.) It just highlights wonderful images, like that Haas HCB image (which I'd never seen), all that much brighter. And what about Constantine Manos's drippingly gorgeous American Color works? What treats for the eyes!

Posted by: Ken Tanaka | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 02:03 PM

Digital curses people with too many choices, and tends to bring out the "more must be better" side of many of us, and not just in color. Many digital black and white shots are ridiculously overdone. And I agree about the Velvia mimicry so common especially for landscapes today (guilty of it myself). I'm waiting for some kind of "counter movement" to the trend, but don't see it yet. Perhaps it's because such a movement wouldn't get many responses on Flickr...

My brother sent me a Denver Post collection of old time color photos that readers might be interested in.

Posted by: John Krumm | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 02:08 PM

Oil painters have used basically the same gook for centuries, giving them time to get past such technological influences.

But my question is about digital "plastic textures." I see what you mean -- but what is it, in terms of light and pixels?

Furthermore, plastic texture seems reduced, even eliminated, with old manual lenses on a micro 4/3 digital camera, for example. So what is going on when the camera is paired with a modern lens, perhaps made by the same corporation?

Posted by: Charles | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 02:10 PM

First, that is a wonderful portrait of HCB! And Mr. Wittig is so right about the over-saturation/over-sharpening problem. Unfortunately, it is drama that wins for the most part. And, I think, there are times when such an approach is appropriate - certain subjects and certain lighting conditions just lend themselves to an over-the-top treatment. But for the first time in my life, I have recently found myself appreciating a good number of pictures made on old-fashioned C-41 film. There was a time when I wouldn't have been caught dead using it, or admitting that I could even tolerate it. Nevertheless, over the last couple of years I have found myself admiring its results - primarily in the hands of users besides me, but still, I have grown to appreciate its subtlety. I still love Kodachrome the best for color, but with it's demise I will have to say that if I shoot color film again, it will probably be some C-41.

Posted by: Jeff Damron | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 02:25 PM

I think if there's any hope it will come when the whole knee-jerk "wow" bubble (with over processed HDR leading the charge) finally bursts and there is a return to a sense of connoisseurship in serious photography, and not just this quest for the quick "wins" you get from all this furious Photoshop dial spinning.

There, I said it. (I also said it on my blog recently, in an anti-HDR screed.)

As a side note, your post brings to mind how the look of Tri-X essentially defined B&W photojournalism for many years (and perhaps still does).

Posted by: Ed Hawco | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 02:33 PM

I started shooting Kodachrome in about 1966, I believe. But NEVER K64 (or Kodachrome-X). Well, maybe two rolls of it, total, in my lifetime. Kodachrome II, and then K25.

I hated the look of K64.

But I kept shooting K25 up through the 1990s, in fact until I started going digital in 2000.

I'm very surprised to see this article, which mostly describes history as I remember it, stated specifically in terms of Kodachrome 64.

(And never mind the nit that 64-speed Kodachrome didn't come out until 1962, and was called Kodachrome-X; actual K64 was 1974.)

Posted by: David Dyer-Bennet | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 03:44 PM

Kodachrome II (ASA25) had a much more subtle palate, with virtually invisible grain, low contrast. Unfortunately, it was superceeded by K25.

I never understood why anyone would want to shoot K64.

Posted by: Bill Mitchell | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 04:14 PM

Funny you mention Velvia as being oversaturated (which it is of course). In my eyes Kodachrome is much the same. It's also oversaturated and unrealistic.

Now Portra NC, that's a nice film with a subtle color palette. (Yes you can't really compare slide and negative film.)

Posted by: Jan | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 04:34 PM

With the demise of Kodachrome can anyone point me in the direction of a slide film which comes "closest" to this Kodachrome aesthetic.

Paul

Posted by: Paul | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 05:19 PM

It's interesting that you assume that the film aesthetic shapes the photographer's aesthetic, rather than the other way around. I remember when Sensia - Velvia's somewhat quieter sibling - came out. I was thrilled that finally, at last, I would be able to have pictures that looked like what I myself saw when I looked around at the world. For those of us drawn to the bright end of the spectrum, especially those beautiful greens, looking at Kodachrome images, while nice, was like viewing the world through yellow-tinted sunglasses. Or, perhaps, like eyes whose lenses had yellowed with age.

For me, at least, Sensia was a film I chose because it mimicked my existing aesthetic preferences. Maybe those preferences are shaped by the film, and now, by digital, but I remain sceptical that it's all a one-way street. There are a lot of digital effects, for example, that I see all the time in current photography, that I have no desire to incorporate into my own work, either at the time of composition or during post-processing.

Posted by: Rana | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 08:20 PM

Paul,

Steve McCurry used K64 when he shot the "Afghan Girl" cover for National Geographic in 1984. When he went back in 2001 to find her, he used E100VS.

Posted by: Daryl Davis | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 08:39 PM

Ken Tanaka-

A very thoughtful observation. Robert Frost famously commented when asked how he felt about the trend toward 'free verse' in contemporary poetry: "like playing tennis without a net". The lack of constraints (like a requirement to adhere to iambic pentameter or a rhyming scheme) in his judgment made it harder to create art. Perhaps the same is true about digital color photography tools. It took me a couple of years to figure out how to use Kodachrome effectively, but it finally felt like I had learned a specific language. With digital capture and processing, now there's no net...and the court is way bigger.

I generally incline toward digital pioneer Stephen Johnson's view, that digital tools make possible a much more faithful rendition of the subtle beauty of colors found in nature. I find it a pleasurable challenge trying to make beautiful landscape prints that are faithful, rather than 'digital Velvia'. But that's just me! Everyone can craft their own way of looking at things using ones and zeros rather than film.

Posted by: Geoff Wittig | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 09:05 PM

If you properly calibrate your camera, monitor, and printer, you should be somewhat close to accurate color. (The new 10-bit IPS monitors are great in this respect.) After white balancing, you get as close as you can get to an accurate rendition of the scene. An unbiased starting point, as it were.

Then, the question is what you do to make a pleasing rendition of the scene; I confess to leaning on LR3’s Vibrance control a bit much! I guess that norms have been set by film cameras, and maybe our eyes have been perverted by those norms. This bias is at least less obnoxious than when the starting point of the image was influenced by a film’s chemistry.

There are parallels in the audio world. Those of us who grew up with vinyl records grew accustomed to the particular noise introduced in the vinyl recording and playback path -- and for a long time A-B testers actually preferred CD sound when that noise was artificially added back in. Scoff if you will, but I wonder if folks will look back at the products that add the look of film grain to digital images and think we’re all barking mad?

Posted by: Richard Kaufmann | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 09:55 PM

Wow, I looked at that Velvia shot for too long and lost a tooth.

Posted by: Karl Knize | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 10:08 PM

Koda-what? Velveeta? What are you guys talking about? The period of contemporary fine art color photography from the 70s up until (and including) the present, has been and continues to be dominated by color *negative* film (not to mention the consumer color photography space, prior to digital anyway, including one-time use cameras). Commercial photography, since 1990, can pretty much be said to be a color negative (and now digital of course) endeavor. I always wonder -- who is shooting all this transparency film? The answer: ardent amateurs. Which is great. Really. I think it's great that there's someone else besides Eggleston shooting tranny film. I'm actually surprised it's still around. Anyway, just so everybody knows, color photography, both for fine art purposes (at least in the sense of fine art exhibited in galleries in coastal and lakeside states) and for commercial purposes (again, magazine photography since 1990 or so) means color negative photography, not transparency. The big reason I think is that you can easily make prints from color negatives, you don't have to worry about an interneg or about some disappearing process like Ciba-, oops I mean Ilfo- oops, I mean it's gone in order to be able to make, ahem, actual prints of your work.

Posted by: Nega-man | Saturday, 07 August 2010 at 11:06 PM

Whoa! That photo of HCB by Haas is bee-yoo-ti-ful! Even given web display and such. The color is expressive and definitely Kodachrome in the best possible way but what stands out, I think, is the emotional expressiveness—you *feel* what Bresson is feeling.

Geoff’s point is good. There are years-long waves of enthusiasm for a look. Roughly paraphrasing, he says that the salient characteristics of an attractive film do far more than simply limit our view of the color green, they change how we look at things and what looks we value at the time. I think you can go further with this.

I’ve noticed over years that when I purchase a new camera (which is of course the very, very best compromise for my money), I go through a period where I find its best stuff and its worst but these eventually fade in the background as I find what the camera and I think is most interesting. In other words, I know wide landscapes are pointless with this fuzzy lens so I find narrow landscapes. I know this verdammter sensor is going to blow out every highlight no matter what I do so I better find places where blown highlights are going to be expressive. I forgot to shoot raw so now what on earth is interesting in these over-saturated, over-sharpened jpegs? And, thank heavens this happens every once in a while: There; got it. I hasten to add that this is subtle: if the camera (“film”) blows too many highlights it gets the heave-ho.

Richard Kaufmann’s comment, “Scoff if you will, but I wonder if folks will look back at the products that add the look of film grain to digital images and think we’re all barking mad?” has truth to it but I just had an interesting 3 days where I experienced its contradiction. (I may have been barking mad.) A house just next door was being demolished and having been in the construction business a few decades ago I was utterly fascinated by the changes in the process. I took out my trusty G10 and started taking pictures. At the end of the first day, I looked at the take and saw that I’d bumped several pictures up to ISO 800 and they looked ghastly-ratty-noisy. “Bah!” said I, “This does not look good; should I even bother taking more?” A G10 at 800 is a grim thing. But the next morning I looked again and thought, “Hm, hm! These aren’t bad! That Canon color, they’re pretty sharp, there’s a feeling there that seems appropriate to the subject. . . .” And so, for the next two days, even when at low ISO, I minimized noise reduction or even added grain (thank you, Lightroom!) in post so all the shots had the same feeling. You can see the result here:

http://www.davefultz.net/Gallery/the_disappearance/index.htm

I feel strongly that I wouldn’t have taken the same pictures with an M9 or a Nikon D-whatever or a Sinar 8 X 10. They stand on their own. The doughty G10 with its horrid high-ISO actually encouraged something pretty nifty.

Dave

Posted by: Dave Fultz | Sunday, 08 August 2010 at 12:30 AM

Nega-man's experience regarding publishers' acceptance of color negative film is very different from mine. I loved color negative film (Fuji NPS) and C-prints, but it was a rare event for a publisher to accept negatives or prints. It was always transparencies.

If I could access RA4 chemistry in my location, I would still be making C-prints, but the digital tidal wave washed away all my sources.

Posted by: latent_image | Sunday, 08 August 2010 at 07:50 AM

Yeah no ad agency, printer, or pre-press house I ever worked with welcomed a color neg. It wasn't until the standard workflow went over to photographers providing their own digital files that (most) commercial photographers were able to use color neg without protest from their clients. I was early on that but still, it was 1993-94 and I was the first in my town, a novelty... it wasn't until 97-98 that delivering a SyQuest (and later a Zip) became more common.

I'm not talking about wedding/portrait photographers, I mean commercial photographers.

Posted by: Frank P. | Sunday, 08 August 2010 at 12:47 PM

There's an interesting section in Annie Liebovitz's recent book where she talks about a moment--I think sometime in the 90s--when she decided to start working with color negative film and met huge resistance from her clients. It was only because she was a famous photographer shooting celebrities that she was able to bully the magazines and ad agencies into accepting negative film.

I'm not a commercial photographer, but I make lots of photographs for promotional literature in a situation where I'm also the editor and I'm buying the printer. My experience in the film-scanning era was that even good prepress operators were not very good at scanning negative film. The folks I work with, just didn't have to do this very much. They were great at scanning chromes and matching them in print, but they really struggled with negative films.

Back to Kodachrome, the recent, excellent book, "National Geographic Image Collection" is organized by subject matter, but within that, the pictures are divided by technology with a subsection in each part of the book devoted to Kodachrome. It's a great way to see this special palette.

Posted by: Robin Dreyer | Sunday, 08 August 2010 at 06:28 PM

Ed: Yes, there are often "wow" bubbles. Some of them last (like Velvia did), some don't. I'm still at the point of finding some of the HDR styles that look over-dramatic attractive -- but it's entirely conceivable that I'll get tired of them, and even if I don't, everybody else may. Then it'll take another generation for people to dare to revisit the techniques for artistic purposes.

Nega-Man: That's not the history as I remember being told about it. Set fine art aside, because that's highly individual with few outside technical constraints. From what I read, it seems to me that magazine and studio shooters went from color slides to digital, mostly without even visiting negatives. I know that the film-based stock agencies were full of slides -- many wouldn't touch anything else for color. Wedding shooters of course shot negatives, since actual photographic prints were their end-product. Studio portrait shooters the same (and in many towns they were the same people as the wedding shooters). But stuff going for four-color mainstream printing, magazine editorial and magazine advertising, was shot on chromes, largely because that's what the printers knew how to work with, until that workflow went digital.

Posted by: David Dyer-Bennet | Sunday, 08 August 2010 at 07:33 PM

@ Geoff Wittig: "rich warm tones and relatively subdued greens"

I've just realised, my sunglasses are like this! Reds and oranges seem to glow when I wear them. All this time I thought they were my John Lennon sunglasses, when really they are my Kodachrome shades!

No wonder I struggle in poor light with them.

Posted by: Roger Bradbury | Monday, 09 August 2010 at 06:24 AM

I think the idea that Velvia destroyed good photography is a bit odd. I don't think I ever shot a subject based on how it would look on film, but because I liked the subject, all of the elements for a good photograph were there, etc...

To the extent the kind of film I used determines the kind of photos I take, it would actually be black and white, which I started out on and shot pretty much exclusively for years. Even now, with digital, I will make a shot with the express purpose of doing it as a black and white.

Posted by: Paul W. Luscher | Monday, 09 August 2010 at 11:41 AM