Edward Burtynsky et al., Burtynsky: Oil

Hardcover; 140 pages

Steidl Photography International

Published October 31, 2009

14.4 x 11.5 x 1.1 inches

(U.K. link

)

Reviewed by Geoff Wittig

Many of the 20th century's greatest landscape photographers consciously embraced an environmentalist ethic in their work. Ansel Adams's long association with the Sierra Club and his tireless devotion to conservation is of course well known. Eliot Porter, Ray Atkinson, Robert Glenn Ketchum and many others pictured the dwindling remnants of pristine landscape as a redemptive Eden, worth preserving before it was all paved over.

While many folks have continued pursuing this idiom, in a world with six billion people and relentlessly increasing pressure on the environment it's harder to find unique corners of wilderness that haven't been photographed already. Confrontational images illustrating environmental degradation have been a feature of work by photographers such as Richard Misrach, Ed Kashi and Robert Glenn Ketchum. (Ketchum seems to slyly insert a few shocking images between more traditional pretty landscapes.) There can be a kind of formalist beauty to such photographs, but it's obviously a much tougher challenge than rendering a snow-capped mountain or forest waterfall attractively.

Edward Burtynsky has built a career in fine art photography meeting this challenge. He began photographing conventionally beautiful landscapes in large format. As he relates in the video Manufactured Landscapes, he had an epiphany while attempting to photograph in the Appalachian mountains of Pennsylvania. He realized that every bit of landscape within sight had been completely reshaped by coal mining. Nothing was "natural." The landscape as reshaped by man instead became his subject.

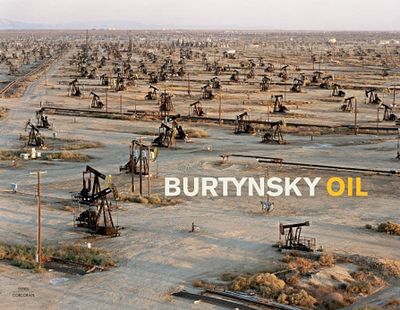

Oil is Burtynsky's latest book. The extraction, distribution, consumption, and declining availability of petroleum are all explored through his large-format photographs.

The opening section examines extraction and refinement. The immense size, geometric order and rectilinear shapes of production fields and refineries make for images of striking formal beauty despite the subject matter, all rendered in fine-grained detail. The cover image, reproduced inside, is a vast diptych of a California production field with endless ranks of derricks, shot in warm late-day light. Another image shot from the air reveals the colossal scale of tar sands extraction.

Next is "Motor Culture," images of the world oil has made. Aerial shots of geometric highway interchanges, the immensity of exurban sprawl, endless rows of new cars awaiting shipment—even Bike Week in Sturgis, South Dakota, gets the same monumental treatment.

Last, and darkest, is "The End of Oil." In this section Burtynsky shows us the final result of the process: rusted out, oozing abandoned oil fields, endless ranks of junked cars and airplanes. Some of the most affecting images show unbelievably vast piles of discarded tires, or the grim oil-soaked reality of recycling in the developing world.

Following the images are essays by curator Paul Roth, writer/photographer Michael Mitchell, and economist/ecologist William E. Rees. Their essays provide a sobering perspective on what the extraction of petroleum, the consequences of its exploitation, and the predicted decline in production mean to civilization and the planet. The essays bracket a short, ironic postscript group of photographs of Detroit's decaying abandoned auto factories.

Oil is a remarkable book for those concerned about where, as an industrial civilization, we are headed in the future. The beautiful photographs of nominally unappealing subjects may cause a bit of cognitive dissonance compared to photographs of a pristine mountain lake; but they're beautiful just the same.

For those interested in Edward Burtynsky's work, there is an embarrassment of riches currently available in book form. Manufactured Landscapes: The Photographs of Edward Burtynsky, catalog to the 2003 exhibition, is still available, though its reproductions are marred by poor shadow detail (U.K. link

). China

(Steidl, 2006) has very good reproductions, which beautifully depict the country's vast factories and frenzied urban construction, together with older coal and steel facilities (U.K. link

). Finally, Quarries

(Steidl, 2009) (U.K. link

) applies the same immaculate large format photography to the mining of marble, granite and limestone. Reproductions are again excellent; large vehicles look like Matchbox toys inside gleaming marble pits in the earth. Great stuff if you like this kind of photography.

Featured Comment by Gavin: "I work in the oil industry, mostly installing offshore platforms and laying pipes, not something Mr Burtynsky has photographed, but it is nice to see some really good, truthful pictures of any kind of industry. The manufactured landscape is all around us; most of the 'wild' landscapes here in the U.K. are anything but. I used to live down in the SW of England and Dartmoor, a popular haunt of landscape photographers, was once one of the most industrialized areas of the World (probably) as tin and lead etc. were mined. It doesn't take much effort to find the remains of the mines and smelters if you know where to look."

Featured Comment by Moose [responding to Gavin]: "From a broader perspective: 'Southern England, for example, is one of the largest structures ever made by man. We think of it as nature: the beautiful expanse of towns, villages, forests and moors that extends from Cornwall to Kent and from the south coast to the Midlands. We think of it as natural, but of course it is man-made, almost all of it. It wasn't there three thousand years ago. It is a consciously created structure, perhaps 300 miles by 100 miles, and it has been created slowly, patiently, over a period of about a thousand years.' Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order, Book One, 'The Phenomenon of Life,' pp. 28-29."

He does do beautiful work, and I've always liked industrial photography. Unspoiled scenery is lovely, as are soaring skylines and graceful towers and bridges. But there's a certain poetry and beauty in human industry and functional infrastructure that some modern photographers seem embarrassed to celebrate. Artists must, of course, be true to their own artistic vision. Personally, though, I've always found this attitude somewhat ironic, considering that photography was arguably the first unique art form of the industrial age.

Posted by: Bryan C | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 10:54 AM

Here is a different view of the problem with OIL.

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/28/arts/design/28john.html?_r=1

Posted by: Jeff Glass | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 11:11 AM

My first impulse after reading this post was to write off the work as yet another selectively photographed, gloom-and-doom collection of "evil industry" photographs meant to instill fear and anger. (Disclaimer: I am an exploration geologist by profession.) But then I paused and had a look at Burtynsky's web site, artist statement, and images. Burtynsky has done a wonderful job of making arresting work from "ugly" subjects. The work is exaggerated toward the "dark side", but I found Burtynsky's message directed not so much toward industry, as toward the consumer. The consumer has not only a right, but moreso a responsibility, to know what's behind their products.

As photographers, we should all be aware that with a different vision, one could make benign and pretty photographs in the same locations.

Posted by: Pat M | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 11:55 AM

I recently came across the TED talk he gave about the project. Pretty interesting: http://www.ted.com/talks/edward_burtynsky_photographs_the_landscape_of_oil.html

Posted by: Finn | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 12:17 PM

If you happen to visit Amsterdam this winter, Huis Marseille will have an exhibition of Burtynsky prints starting next week.

http://www.huismarseille.nl/

The house itself is also worth a visit.

Posted by: Robert M | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 12:32 PM

Burtynsky's deep personal connection to this topic is related by Tyler Green in his "Modern Art Notes":

http://www.artsjournal.com/man/2009/11/introducing_edward_burtynsky_o.html

I applaud and appreciate Burtynsky's intent, ambition and accomplishment as represented in the book and exhibit, and admire his work in general.

However, my one quibble with this monumental work, especially in light of its title, is (ironically) its limited scope. Granted, the production of oil and motor culture and its consequences are dominating and toxic aspects of the dominant culture of this planet. But we citizens of that culture seldom contemplate how widely and profoundly oil pervades every aspect of our existence and dictates our political, social and economic priorities. What and how we eat; how we dress and groom ourselves; how we wash and clean, and entertain ourselves; how, where and why we engage in armed conflicts and occupations... all dictated or heavily influenced by oil reliance.

A propos this gathering: just about every aspect of digital photography is made of oil--from the materials and methods used to develop and produce the equipment to the inks and screens used to reproduce and present the image. And, of course, oil gets all of those things into many hands at affordable prices.

Posted by: robert e | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 02:30 PM

I'll also recommend the video, which I picked up at the exhibit of "Oil" at the Corcoran Gallery of Art currently running through 12/13.

The video concentrates on industrial development in China, including the "Three Gorges" Project.

- Tim

Posted by: Tim Medley | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 04:03 PM

Thank you for this article, Geoff. I have been both fascinated and inspired by Edward Burtynsky's meticulous imagery of such scenes for some time. Seeing the original prints is a real treat.

I also recommend the "Manufactured Landscapes" video. Thank you for reminding me to get the catalog.

Posted by: Ken Tanaka | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 08:32 PM

I can appreciate a natural landscape as much as the next person but damn I love industrial shots like the one above.

Glistening metal is one of the most under appreciated subjects IMO. Abstract sections of trucks, trains, junkyards and heavy equipment added to industrial pipe configurations do my heart good.

Posted by: MJFerron | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 10:24 PM

If the opportunity arises to see an exhibition of Burtynsky's work grab it. The prints are absolutely stunning, technically and artistically.

Posted by: Paul Amyes | Tuesday, 24 November 2009 at 10:59 PM

It's landscape photography of this kind that really interests me. The moment I saw the shot of the refinery I thought of Bernd and Hilla Becher's Typologies which are beautiful but feel more like a scientific exploration than a photographic one. For me Robert Adam's is much more interesting than Ansel Adam's and there's definitely some truth and landscape in Edward Burtynsky's Oil

Posted by: Sean | Wednesday, 25 November 2009 at 06:40 AM

"If the opportunity arises to see an exhibition of Burtynsky's work grab it. The prints are absolutely stunning, technically and artistically."

His Oil exhibition is coming to the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, this spring. Only a 250 mile drive from me, which I'll make. The irony

Posted by: Sean | Wednesday, 25 November 2009 at 09:56 AM

The opportunity has arisen if you can get to Ottawa, Canada before 31 January. Go to the Carleton University Art Gallery to see 22 examples of Mr Burtynsky's China work:

http://cuag.carleton.ca/index.php/exhibitions/36/

Posted by: Dave Elden | Wednesday, 25 November 2009 at 11:40 AM

"The manufactured landscape is all around us; most of the 'wild' landscapes here in the U.K. are anything but. I used to live down in the SW of England and Dartmoor, a popular haunt of landscape photographers, was once one of the most industrialized areas of the World (probably) as tin and lead etc. were mined."

From a broader perspective:

"Southern England, for example, is one of the largest structures ever made by man. We think of it as nature: the beautiful expanse of towns, villages, forests and moors that extends from Cornwall to Kent and from the south coast to the Midlands. We think of it as natural, but of course it is man-made, almost all of it. It wasn't there three thousand years ago. It is a consciously created structure, perhaps 300 miles by 100 miles, and it has been created slowly, patiently, over a period of about a thousand years."

Christopher Alexander,

The Nature of Order, Book One, The Phenomenon of Life, pp 28-29

Moose

Posted by: Moose | Wednesday, 25 November 2009 at 02:01 PM

Well, that's most of my Christmas shopping done in one post, including my self-present. Thanks, Mike!

Posted by: Ludovic | Wednesday, 25 November 2009 at 04:37 PM