So I want to talk about leveling the camera. Or the world. Well, actually, both—because when you tilt the camera, of course, you tilt the world in your picture, too.

It amused me that the Earth and the skies in this scene seem to be tilting in opposite directions.

I don't always use the leveling feature of cameras that have them. I usually leave them on, but I find it easy to ignore them. I've always been of the opinion that it's better to get the picture to feel right than it is to get it to be right. The apparent "tilt" of the clouds and the tilt of the horizon line in the shot above oppose each other, so if you corrected one till it looked more or less "level" you'd make the other look completely wrong.

This was just coincidental, of course—an accident of perspective and a gently sloping hill. In this shot, I did use the camera's leveling index—the camera was perfectly horizontal when the exposure was made.

Horizon uncertainty

Up here in the Finger Lakes, I've noticed that I've had more trouble leveling the camera than I used to have. I can't quantify that; it's just a feeling I have. It's not as easy, somehow, to get the picture to "look right" purely visually.

Here's a good example. Does this look straight to you? This was taken very late, just before twilight. I saw the clouds approaching from the top of the hill as I was driving home and drove to a hotel parking lot at the head of the East branch of the lake knowing I could get an unobstructed view from there. I wasn't out photographing and only had my iPhone. Curiously, this sky lasted for only about five minutes before it dissipated and became ordinary again.

It was dark enough that I could see the viewing screen perfectly well, but I couldn't easily figure out how to angle the device so the scene looked right. The shoreline on the right is at a steep angle to where I stood, but the shoreline to the left is more perpendicular to my sightline. In the middle of the picture we're seeing more than eight miles down the East branch of the lake to the south. The actual waterlines are all but hidden in the dark reflections of the land. Again, as in the top picture, the striations in the cloud formations look like they're slanting upwards from left to right. It looks like the whole picture needs to be tilted down at the right, doesn't it?

(Down by the water I met a nice couple from Pennsylvania who were staying at the hotel. They asked me to take a portrait of them using their phone with the dramatic skies as a background. I moved them where I wanted them and took several and then asked them to check that they liked it, offering to take another if they didn't. They looked at it and the woman exclaimed, "Ooh, look at you, all creative! You're hired!")

I was holding the phone almost perfectly level when I took this, but the reflections of those two distant lights tell me that the right side of the picture should even be a tad higher than it is...even though it already looks a little too high to me. I've played around with the picture in Photoshop and found I couldn't tilt it such that it would snap into "looking right" as often happens with all sorts of corrections.

Anyway this is just an example. With our steep hills, long, narrow lakes, and turbulent, changing skies, this sort of "horizon uncertainty" seems to happen to me a lot up here. I notice because I find myself looking at the leveling line in the camera viewfinder more often, just out of curiosity. Then I'll level the camera according to the index and think, "really? That's leveled? That doesn't look level."

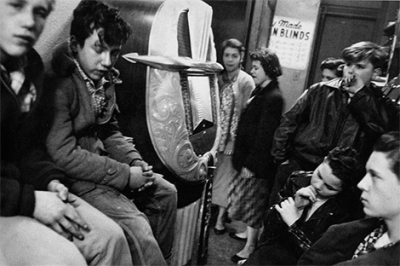

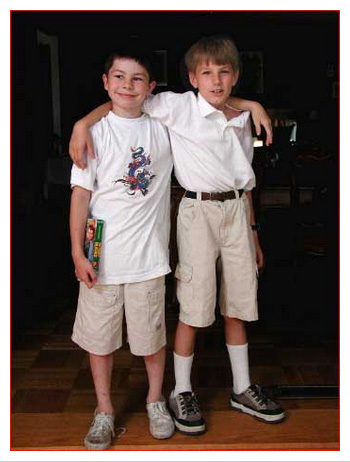

A photo by Garry Winogrand from the quixotic project Women Are Beautiful

Squared and true

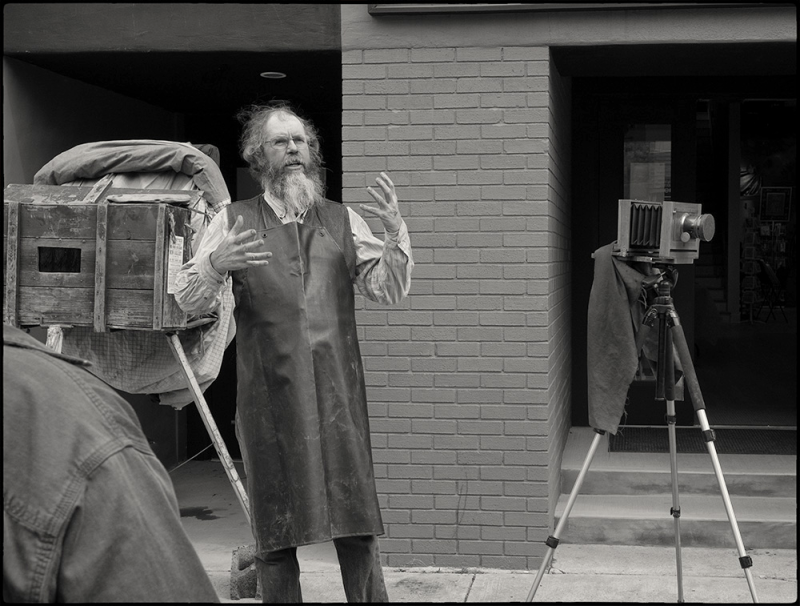

A number of photographers, most notably Garry Winogrand, deliberately tilted the camera as part of their compositions. Winogrand used tilt as part of his strategy to make pictures that didn't look like what people expected photographs to look like. I know from long experience that a fair number of photographers are meticulous or fastidious (the more pejorative words might be fussy or picky) about leveled horizons, and are "bothered" by camera tilt. Especially horizons on water. I'm not, although I do typically hold the camera level. How do you feel about it? There was one camera—I forget what it was—that I naturally held at a slight slant for some reason; the viewfinder wasn't right when the camera felt right. I found I often had to correct myself. It does depend on the camera you use, of course. Large format photographers, who typically set up very carefully, often use spirit levels, which are sometimes built into the camera body, to get the camera squared and true. Winogrand, on the other hand, used a Leica one-handed.

A horizon leveling index line in a camera viewfinder is one of many camera features that are new since the film era. I like 'em; it never hurts to know when you're on the level. And, lately, as I say, I find myself referring to it more than ever.

Mike

Original contents copyright 2017 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

Always on the level.

Give Mike a “Like” or Buy yourself something nice

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Geoff Wittig: "Hah! I find the in-viewfinder leveling feature essential. Even when I'm composing on a tripod, somehow I always manage to have the left side sloping down unless I consciously correct myself. It did help somewhat when I finally got a tripod tall enough for me.

"Here in the Finger Lakes, part of the problem is the bizarre topography. The hills around the lakes all get taller and steeper as you head south, and the shale/limestone strata are all gently tilted, so if you match your frame to (say) the rock ledges at a waterfall, it will often be a tad off for the horizon, and nothing looks right. I painfully discovered this when I proudly showed a slide of the waterfalls on our property at a critique led by the estimable John Shaw. To my dismay I saw the entire crowd tilt their heads to the left in unison in an effort to square my image with reality. In my defense, the rock strata did not match the horizon. But it still looked 'off.' Now I try to make sure the image looks true, regardless of where 'level' really is. And oddly the viewfinder level helps a lot with this."

Michael Poster: "I’ve always thought of camera angle as a way to promote an 'active' frame or a 'settled' frame. So a tilted camera (fore and aft and/or side to side) is more likely to contribute to an active picture while a level camera helps settle a picture.

"I also find 'level' removes yet another set of decisions that get in the way of the kind of pictures I want to make. As in: should I tilt? fore or aft? side to side? should I zoom in or out? Should the picture be horizontal or vertical? By the time I’m through with all those decisions, I’ve lost the image. I try to shoot level (mostly) I shoot square, I use a 35mm (equivalent) lens. But almost all my pictures are portraits in one way or another so the question of how to shoot unpeopled pictures rarely comes up."

Stan B.: "Tilting the horizon is but another valid tool, that can either make or break a particular photo compositionally—and yes, like anything else, can be overdone.

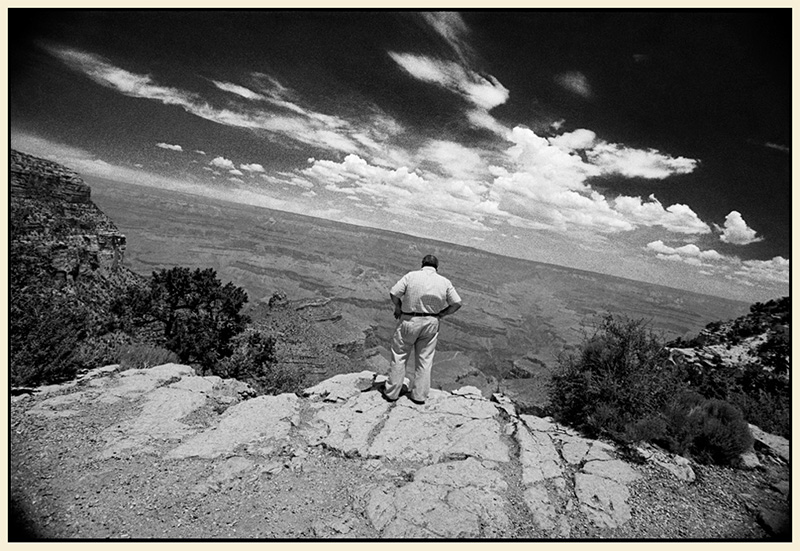

Stan Banos, Grand Canyon

"Curiously, some who proclaim someone 'anal' because they do not crop, are themselves adamant about level horizon lines. Decades after Winogrand, you still have people who furrow their eyebrows when confronted with a tilted horizon.... Egads!!!"

Craig Beyers (partial comment): "I find I mind when a clear horizon line is tilted slightly as it implies (to me) a lack of concern or carelessness—OK, laziness—quite a bit by the photographer. When it's clearly tilted by choice like the Winogrand example, I know it's an intentional compositional technique, not a mistake, carelessness, or laziness."

[The full text of partial comments can be found in the Comments section. —Ed.]

brad: "When talking to a younger photographer, who's quite good and a successful pro, the term 'horizon management' was used. I knew what he meant but had never heard the term. He's well educated, and I think it came from his East coast school's photo department. He was saying that among the prerequisites for image-making, you needed to properly master it. I agree...but never thought of it in such an academic sense. I wonder if there's a bot...scrubbing the web collecting photo data for a statistical analysis of Horizon Management Failure? A workshop will surely address this serious issue."

DavidB: "I encounter this issue photographing scenes here in the Southwest—especially the Grand Canyon. Both the North Rim and South Rim of the canyon are not level but gently rise and fall several thousand feet over the length of the canyon. Furthermore, the North Rim is over 1,000' higher than the South Rim so a photograph that includes both will look wrong. Getting the camera level results in tilting horizons—but that's just the way it is."

Michael: "The photo in Stan Banos's comment is a super example of how a tilted horizon can improve a photo's truthfulness. It conveys that feeling of vertigo that you feel (or at least I do) when I suddenly stand on the edge of that awful / awe-ful space, that stupendous drop."

Paul Van: "I have found that using a focusing screen with a grid has helped me immensely to organize both vertical and horizontal lines within the frame. Mostly, I suppose, by giving me a reference line for important elements within the composition."