By Martin Munkácsi, 1928 (hand-worked negative)

_____________

(Thanks to Dibutil, and Oleg O. Moiseyenko)

Question from Scott Kirkpatrick: "What's a "hand-worked negative"? Something like a Gene Smith ferricyanide bleach job to get all possible detail out of a long-scale negative? Does this have something to do with why the stands in the background are greyed out while the figures in the foreground are crisp and contrasty?"

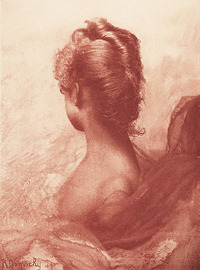

Mike replies: One of my favorite New Yorker cartoons is of a crow sitting on a windowsill, saying, "At the risk of being obvious, I'm a talking crow." Well, at the risk of being obvious, a hand-worked negative is a negative that's been worked on by hand. When photographers used bigger cameras they got bigger negatives, so they could retouch directly on the negative, which is the job Edward Weston used to complain so bitterly about when retouching the portrait negs he did for pay would keep him indoors instead of out photographing for his art. The pictorialists often took retouching further, essentially "drawing" on their negatives to bring out properties and qualities they wanted in the image. In many cases the easiest manipulation was that you could "draw in" extra highlight density. The ultimate example was probably the French photographer Robert Demachy, the great gum printer, who believed a photograph wasn't art unless the negative had been altered by the photographer (that's his "Study in Red" above right), although many of the pictorialists also did it

to some degree. Munkácsi was working before the "straight" aesthetic was elaborated in the 1930s, and so, although he wasn't a pictorialist, he used some of the technical conventions of pictorialism that were standard for the era, including hand-working of negatives. If you click on his image above to get the larger version, you can clearly see hand-drawn crosshatching in various places on the two figures.

The folds of the clothing and the hands of the figure on the left have been worked on as well.

Mike replies: One of my favorite New Yorker cartoons is of a crow sitting on a windowsill, saying, "At the risk of being obvious, I'm a talking crow." Well, at the risk of being obvious, a hand-worked negative is a negative that's been worked on by hand. When photographers used bigger cameras they got bigger negatives, so they could retouch directly on the negative, which is the job Edward Weston used to complain so bitterly about when retouching the portrait negs he did for pay would keep him indoors instead of out photographing for his art. The pictorialists often took retouching further, essentially "drawing" on their negatives to bring out properties and qualities they wanted in the image. In many cases the easiest manipulation was that you could "draw in" extra highlight density. The ultimate example was probably the French photographer Robert Demachy, the great gum printer, who believed a photograph wasn't art unless the negative had been altered by the photographer (that's his "Study in Red" above right), although many of the pictorialists also did it

to some degree. Munkácsi was working before the "straight" aesthetic was elaborated in the 1930s, and so, although he wasn't a pictorialist, he used some of the technical conventions of pictorialism that were standard for the era, including hand-working of negatives. If you click on his image above to get the larger version, you can clearly see hand-drawn crosshatching in various places on the two figures.

The folds of the clothing and the hands of the figure on the left have been worked on as well.

The light background is a result of overexposure due to excessive UV. These days, lenses have coatings and sometimes even cement between lens elements that cuts UV, so that an additional UV filter isn't really needed. In the '20s, before lens coating, and when they sometimes used organic cements (purified pine pitch, even) for lens elements, a UV filter had a larger effect. It was sometimes called a "haze-cutting" filter; the light background you see in this picture and many other pictures of the period is, in effect, the "haze." I often quite like the effect, personally, although of course it depends upon the picture.