"Summer Storm, Chicago" by Ken Tanaka. A print offer from 2010.

"Summer Storm, Chicago" by Ken Tanaka. A print offer from 2010.

I'm very happy about our occasional print sales. We don't do very many of them—only two all of last year—but the sales and marketing model we've developed is very pleasing to me. Here's the difference:

Traditional gallery show: The artist/photographer/creator (whatever word you want to use) is responsible for making fine prints of all the work to be shown, plus paying for matting and framing. The out-of-pocket costs of all that can be hundreds to thousands of dollars. The costs of promotion, hanging the show, printing invitations, etc., as well as the costs of the opening, are tradtionally borne by the gallery, although in some cases the photographer has to pitch in for that as well—I've known of cases where the photographer has to help hang the show and pay for the wine and cheese for the opening!

In any event, the show is essentially done "on spec" (speculation). No one knows in advance how many prints will sell.

Then, because the sales will be few, the prices for each print have to be high. When I got into photography in the 1980s, anything up to $350 was considered a "student price." Established adult photographers would charge $500 up to as much as the market would bear; for smaller galleries, average sale prices might be anywhere from $650 to $1,800 depending on the size and rarity of the art, the popularity and fame of the photographer, the inherent desirability of the work, and all the other intangibles. Naturally, more famous photographers at the best galleries can charge much more; I've seen prices of up to $120,000 on gallery artwork. The reductio ad absurdum in my own experience was a New York City show of vacation snapshots by a famous painter. The pictures were utter junk, just random snapshots, but the prints were 16x20 dye transfers and the price for each was $25,000. The gallerist gushed to me that the artist had only shot two rolls of film on his vacation but that "every shot was a masterpiece" because he was a visual genius and his genius transferred readily between mediums, and also that the pictures were an "unprecedented opportunity to own a signed [famous name] for such an incredibly low price."

If she says so. I hope they did well with that.

But back to our typical gallery show—the show might be up for a month, maybe two. The gallery will sell a handful of prints; I've known photographers who sold no prints at a gallery show, one who sold two, many who sold four or six or eight, and several whose shows were "huge successes" who sold as many as twenty or thirty prints in a single show. A gallerist in the Eastern city where I went to art school told me that her best show ever sold 60 prints.

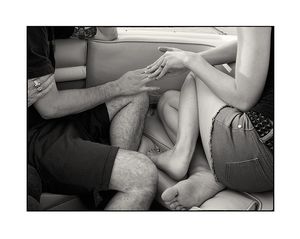

A beautiful platinum/palladium print by Carl Weese offered in 2010.

I should mention that sometimes, because the photographer wants to impress the gallery, the photographer will do a lot of marketing themselves, and arrange for buyers and collectors they've developed through other channels to go to the gallery and buy prints from the show. They want the gallery to think they're a good draw. Makes some sense.

So let's say it's a decent photographer with a track record and a fair amount of name recognition, and the prints are priced at $1,200, and the show does well and sells ten prints over the course of the month. That's $12,000 gross. The photographer then has to produce and deliver any duplicates of prints that have sold, again on their own dime. And the gallery will take 50%, 60%, or even 70% in gallery commission from the proceeds...leaving the photographer with $6,000 to $3,600 in profits. Subtract the $500 to $2,000 it cost the photographer to print and frame the show, and...well, you'd better not start to think too hard about the dozens to hundreds of hours of work the photographer put in to just to prepare for the show...never mind the work, effort, time, and care it took to actually do the photography and produce the body of work in the first place!

I'm not saying traditional galleries are bad. They're not; they're great—they do a huge service to photography as art, by promoting photography to the public, and helping keep working photographers alive. In fact, as "friends of photography," gallery owners are often just as passionate and dedicated to the medium as photographers themselves.

It's just a hard way for photographers to make a living, is all. Many's the time I've heard of photographers having a "big show" at a name gallery, working like dogs for several months of their lives to prepare for it and help promote it—and coming out the other end having lost money.

Another little problem I won't discuss at length here is that galleries usually only handle a few living photographers—ten, twenty, or thirty, maybe. Have you ever tried taking your portfolio around to galleries to see if they're interested in representing you? Let's just put it this way: if you're not already doing well on your own, you're not going to stand much of a chance.

And don't forget that the ten people who each bought a fine print of a picture they loved had to pay $1,200 for the privilege, in our example. That's pocket change to some people, but it leaves a significant part of the population out of the game.

Gordon Lewis's "Precipitation," offered in 2009.

TOP print sales: We do it differently. Our sales last for five days only, and the largest number of prints we've ever offered is six. The photographers don't have to print a whole show; they don't have to pay for matting or framing or invitations, or help with promotion, much less spring for wine and cheese. We price the prints much lower than gallery prices: so far our print prices have ranged from $19.95 to $395. We take orders in advance, over the five-day sale period. After the sale is over, the photographer has a set number of paid orders in hand. He or she can then begin to produce the prints "en masse" knowing in advance that each one is already sold.

The average profit per print might be much less, but the profit for each one is assured because each print has already been sold, and by production-lining the prints the photographer can make the prints very efficiently.

And, TOP's "gallery commission" is 20% vs. a gallery's 50–70%, leaving the photographer with 80% of the sale price. I can reasonably guarantee that there isn't a full-time professional gallery in the world that takes a sales commission as low as 20%.

A few weeks to a couple of months of hard work later, and the photographer is left with a nice big chunk of money (in one case, the amount was equal to four times the 2006 average annual household income in the United States).

All this means that we can make the sale prices much lower than galleries ever could. TOP readers—you—get a chance to buy original artwork for a fraction of what it might normally cost—in several cases, less than it would cost to have a lab print one of your own pictures by the same method. We've sold platinum/palladium prints for $180 and dye transfer prints for $100—far less than any gallery could offer. (Granted, both those prices turned out to be too low. But we're learning.)

This is why I call our sales "win-win-win"—I win, you win, the photographer wins. Nobody loses.

Well, at least I think nobody loses. Some people say we're doing photography a "disservice" by undervaluing it—the traditional argument against discounters. But I would counter than in many cases, buyers from our sales are purchasing original artwork for the first time in their lives. Is it a bad thing to create new customers for photography who weren't customers before? Is it bad for the medium to encourage people to buy original art from living artists as opposed to buying a printed poster of a picture by a dead artist from a museum shop? With each of our sales, dozens of people start thinking of themselves, for the very first time, as buyers of original art, and patrons of practicing artists. Even traditional galleries will admit that it's not a bad thing to attract new blood into the customer base.

And of course, people who have little money can be just as appreciative of fine prints as people who have a lot. There's no correspondence there whatsoever.

Of course, there are drawbacks to our model. First and foremost, it's surprisingly hard to find the right kind of artist—someone who's iconoclastic enough to embrace our sales model but professional enough to be able to fulfill the sales...not to mention good enough that our audience will appreciate their work. That sort of person isn't common. In the past two years I've probably approached a dozen photographers only to be turned down outright or have a sale idea fizzle and die for any one of a number of reasons.

And, of course, buyers' choices are limited. And you have to grab the opportunity while you can—our order-in-advance scheme means you have to order during the limited window that ordering is open. Once it's over, it's over. Still a few flaws in the ointment, as my brother used to say.

Our first sale of 2013 starts tomorrow at noon Eastern time. If I get my act together, it won't be the year's last.

Mike

Original contents copyright 2013 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Tim Bradshaw (partial comment—to read Tim's entire comment, please see the Comments section): "...Although

I think the TOP print sales are admirable, I also think that they do

not do the same job as a gallery, where you get to see either the print

you will buy or something that should be visually very similar (and I

think you'd have reason to complain if it was not).

"Related to this comment is something I've said before: the increasing

uniformity of the way people look at photography (via a computer screen

and usually a poorly-calibrated screen at that) is damaging. I am

fairly sure I have argued with people who thought that daguerreotypes

were well-represented on screen, for instance: I can only assume they

had never seen one. They are obviously an extreme case, but the same is

true for almost any traditional printing technique (or in fact for

projected transparencies): there is no substitute for seeing the thing itself, and as fewer and fewer people do that we will forget what the things were like at all."

Mike replies: Ironically, that was originally the very justification for these sales: to put examples of various techniques in peoples' own hands and homes so they could see and experience them, study and live with them for themselves.

My opinion is that it helps greatly to "calibrate your eye" when looking at onscreen JPEGs of artwork if you have some idea of what originals look like. For instance, I've seen thousands of original albumen prints over the years. When viewing a JPEG representation of an albumen print online, I'm convinced this lets me "see" something very different than someone who has never seen an original—I'm calibrating the approximate and inferior onscreen input with my knowledge and experience of what it "probably" really looks like...which I'm able to do to some extent even if I've never seen the original of that particular picture.

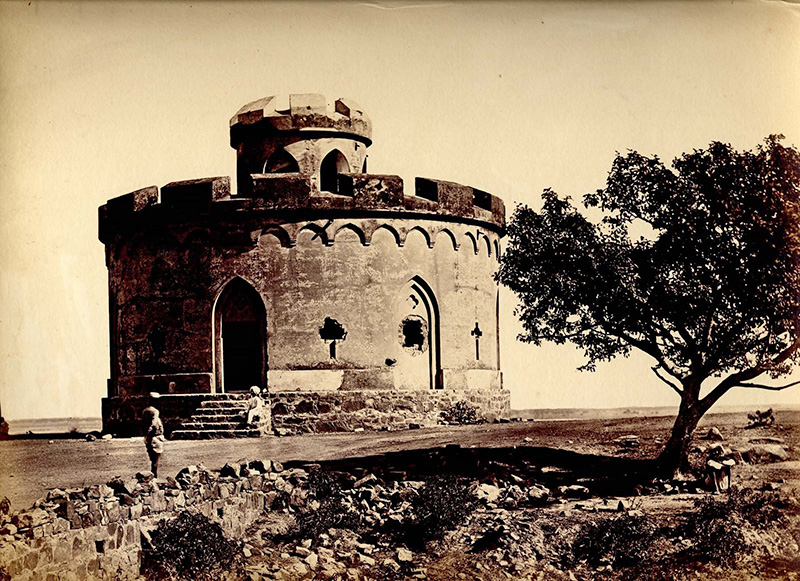

Flagstaff Tower, Delhi, 1858-9. A small JPEG of an albumen print by Felice Beato. I've never seen the original picture, but I think I see something very different in this JPEG than would a person who has never seen an original albumen print and doesn't know what they look like.

Flagstaff Tower, Delhi, 1858-9. A small JPEG of an albumen print by Felice Beato. I've never seen the original picture, but I think I see something very different in this JPEG than would a person who has never seen an original albumen print and doesn't know what they look like.

Gordon Lewis: "As someone who has had the honor of being asked to offer a print—'Precipitation'—through TOP's print sale, I can also understand why many photographers

would decline to participate. Just as there is a lot of time and expense

involved in selling through galleries, it's more than a notion to

fulfill a TOP print sale. Assuming the sale is a success, fulfillment

can involve making hundreds of prints, each of which needs to be as

close to perfect as you can manage. You then have to package each one

such that it reliably protects the print from shipping damage yet

without incurring excess charges. International shipments are

complicated by the need to fill out customs forms and pay different

shipping fees for different countries. This takes time, attention to

detail, and organization—a combination which not everyone has in

abundance. Suffice it to say that even Mike himself has been reluctant

to offer his prints for sale, even though in his case he gets to keep

all the profits."

Mike replies: In many cases the amount of work, care, craftsmanship, and organization that has gone into fulfilling these sales has been almost heroic in scale and intensity. It takes a huge amount of experience, ability, skill and expertise to make hundreds of platinum/palladium prints, to name just one example—in that case Carl and I underestimated just how much work it would prove to be for him, and we really should have priced the prints much higher to reduce the number sold.

The #1 thing I look for in a print sale photographer is reliability—I have to believe they'll be able to reliably fulfill the sale. It takes a high level of professionalism to be able to do so, regardless of whether the photographer is an amateur or pro.

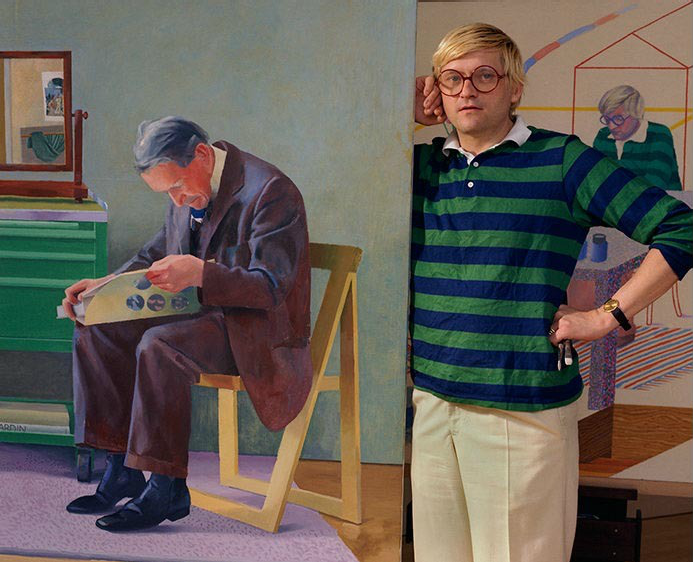

An interesting thing to note is that sometimes printmaking is so painstaking that very successful photographers often in effect "sell too many" prints—they don't have the time or energy to even fulfill all their paid orders...or it just takes too much time away from making new work. I seem to recall that at one time John Sexton had a several year backlog for delivery of sold prints, and Sally Mann made several attempts to hire a darkroom assistant who could make her prints to her satisfaction—and she wasn't able to find anyone (at least as of the time I heard the story). She had to continue making her prints herself. Recently I heard that Paul Caponigro is so tired of printing his most popular picture ("Running White Deer") that he's declared a moratorium on orders—even though they sell for $6,000 to $8,000 each. (I don't have firsthand knowledge of all of these cases, so please don't quote me.) Obviously, Paul would not be even remotely interested in doing a TOP sale of "Running White Deer"!