Seems we crashed Lodima Press's bookstore last night for quite some time. It's back up and running now.

At this point it looks very likely that Edward Weston: Life Work will sell out entirely in this sale, and most likely well before Tuesday. So if you find yourself sitting on the fence about it, you may not want to hunker there too much longer.

UPDATE: The edition sold out at about 9:10 p.m. tonight (Friday). (There are a few copies of the deluxe edition still remaining.) Our thanks to everyone who participated—I really hope you enjoy the book!

And my sincere thanks to Michael and Paula for making this possible.

• • •

One of the treats of this book is "A Couple Collects Edward Weston," the brief joint essay by Judith G. Hochberg and Michael P. Mattis that introduces the magnificent plates. They manage to convey both personality and erudition, opening a well-lit window into the passion and enthusiasm collectors feel for the objects of their hunt. We're taken from their beginnings in collecting to their decision to concentrate on Weston...

Michael and I both consider Weston the "Picasso of Photography." One needs only to think of his mastery of past modalities and invention of new ones, his success in a variety of genres, his economy of line, his self-knowledge as an artist, his intense relationships with other artists—and with the women in his life.

...all the way to their debt to those charged with the care of the Weston archives and their friendships with the Weston family members who are alive today. Talk about economy of line, or of word...the essays are short and sweet, but insightful.

I thought it was interesting that the idea of an exhibit of their Weston prints went from a "dream" to an "obligation," and that, by the time the exhibition became a reality, it was the only way they themselves could see all their own Weston prints on the wall at the same time.

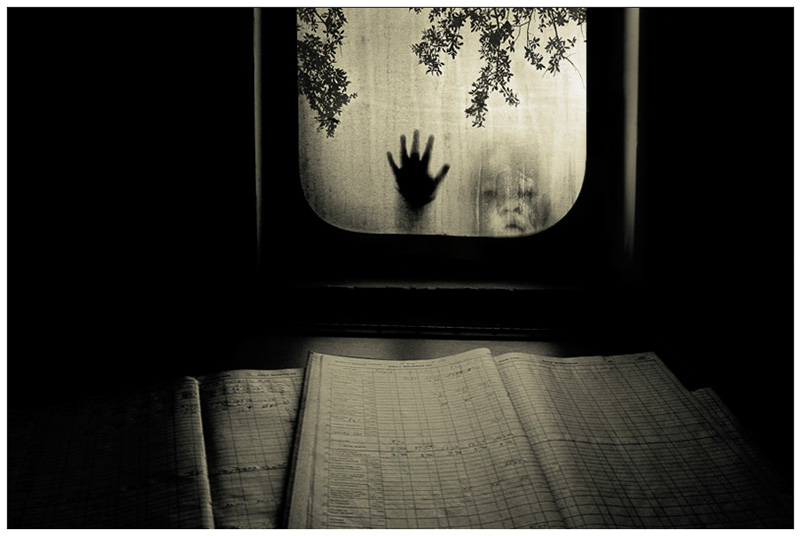

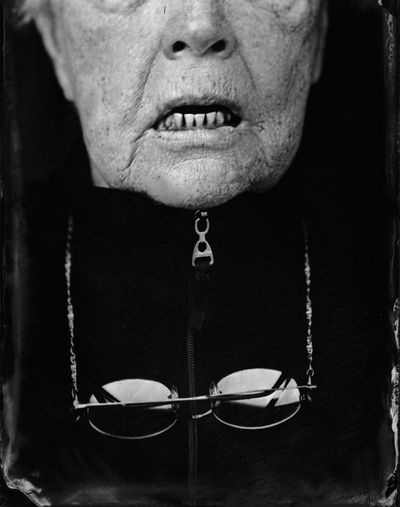

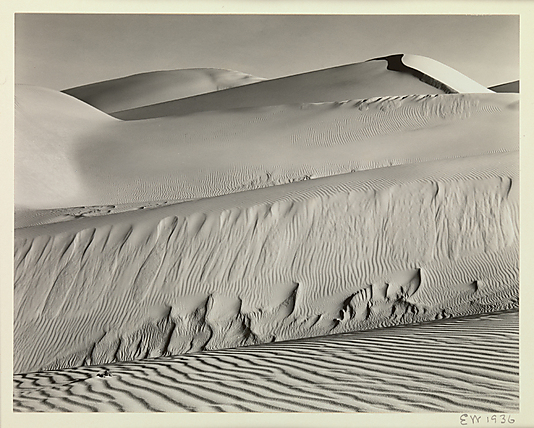

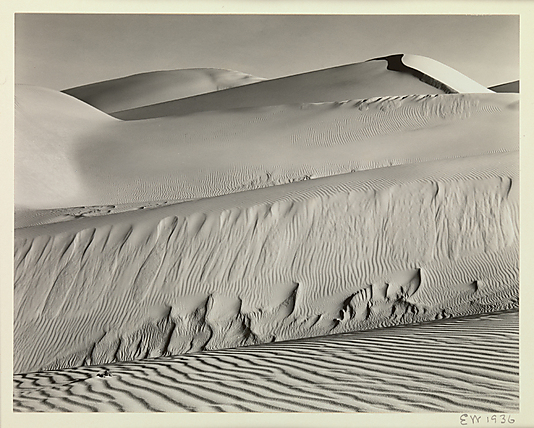

Edward Weston, Dunes, Oceano, 1936. This is a JPEG of the Met's print.

Edward Weston, Dunes, Oceano, 1936. This is a JPEG of the Met's print.

My first encounter with Life Work was interesting. Art critics from Ruskin to Berger talk about the "aura" of original art-objects, and I'm sure you know the feeling yourself—the special qualities that convey when you're looking directly at the real thing on a museum or gallery wall. There's a sense of immediacy and connection—Goya touched that!—and a sense that the veil of intermediacy has been removed: you're face to face with the art itself, and all its secrets are there for you to see. It needs no "translation," requires no imaginative help.

I've of course seen many original Westons in my life, and got to know one of them—Dunes, Oceano, a.k.a. White Dunes—intimately, because one of the schools where I taught had an original print of it on the wall. The plates in Edward Weston: Life Work are the first time, I think, that I've ever felt, from a book, that feeling, that sense, you get when looking at the real thing. It's a feeling I know well, and I felt some of it—more than a glimmer—from looking at many of the later plates in the book. Remarkable. I'm not sure any book has ever done that for me before.

I mentioned "Red Ceiling" yesterday, which is apropos, because Eggleston is on record saying that reproductions have never captured it. (And he's right, at least in my limited experience.) He's quoted in this passage from Mark Holborn's introduction to Ancient and Modern:

The first [dye transfer prints Eggleston] had made were of the image of Greenwood Moose Lodge, a sombre, windowless edifice against a blue sky, and The Red Ceiling

in 1973. He was so impressed with them that he knew dye transfers were

going to provide him with his medium. He immediately sent [MoMA Photography Department Director John] Szarkowski a

print of The Red Ceiling, which was to become one of his most

famous images. The cross of white cable leading to the potent, central

light bulb, was what he described as a "fly's eye view" in the guest

room of his friend, a dentist in Greenwood, Mississippi, whose choice of

decor included an adjacent blue room; he [that is, the friend] can be seen naked, his walls

daubed with graffiti, in The Guide . The house with the red room

was subsequently burned down and his friend murdered, yet far from

having any sinister connotation, the red room was immensely pleasing to

Eggleston. "The Red Ceiling is so powerful, that in fact I've never seen

it reproduced on the page to my satisfaction," Eggleston claimed. "When

you look at the dye it is like red blood that's wet on the wall. The

photograph was like a Bach exercise for me because I knew that red was

the most difficult color to work with. A little red is usually enough,

but to work with an entire red surface was a challenge. It was hard to

do. I don't know of any totally red pictures, except in advertising. The

photograph is still powerful. It shocks you every time."

. The house with the red room

was subsequently burned down and his friend murdered, yet far from

having any sinister connotation, the red room was immensely pleasing to

Eggleston. "The Red Ceiling is so powerful, that in fact I've never seen

it reproduced on the page to my satisfaction," Eggleston claimed. "When

you look at the dye it is like red blood that's wet on the wall. The

photograph was like a Bach exercise for me because I knew that red was

the most difficult color to work with. A little red is usually enough,

but to work with an entire red surface was a challenge. It was hard to

do. I don't know of any totally red pictures, except in advertising. The

photograph is still powerful. It shocks you every time."

Those of you who own a dye transfer print of your own from one of our two dye sales can probably well imagine what he means.

But I think that, for example, Weston's famous Pepper No. 30, plate 43 in the book, among others, really is reproduced satisfactorily on the page. Of course you're not fooled into thinking you're looking at a real print, but for me, at least, it imparts that same "direct" feeling, the feeling that you're seeing the picture itself, without translation into ink.

Michael A. Smith tells a story about this:

In Edward Weston: Life Work, there are a few photographs that have never been reproduced before, many that have been reproduced very seldomly, and a few that have often been reproduced. One of the latter is the famous Pepper No. 30. We know the collector who owns Edward’s own copy of Pepper No. 30. Edward considered it the best print he had ever made from that negative. Eventually, Edward gave the print to Brett. And Brett gave it to a friend whose father was Brett's closest friend and who had grown up around the Westons. The friend sold it to this collector in 1974. (Way too soon.)

When we showed the collector the book we published, he brought down this print of Pepper No. 30, which we had seen previously, and placed it next to the reproduction. We (me, Paula, the collector and the collector’s wife) looked very carefully at the print and at the reproduction, trying to find differences. There were a few, but they were virtually imperceptible without extremely close scrutiny, and even then, truly, there was hardly any difference between the print and the 600-line screen quadtone reproduction.

After about three minutes of this intense looking the collector's wife said, "You know, I think I like the reproduction better."

Bet her husband didn't like that.

Mike

Original contents copyright 2012 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

No featured comments yet—please check back soon!