By

Ctein

A recent column generated a number of speculative and Monday-morning-quarterback comments about Kodak and the changeover to digital. I'd like to reset the record.

Mind you, I am not saying Kodak has successfully made the transition; I think there is still a real possibility the company will go under. But the assumptions that people have been making that it's from lack of trying, lack of foresight, or an unwillingness to commit aren't supported by Kodak's history. Over the past quarter-century, Kodak has made 3.5 major attempts to grab a commanding position in the world of digital photography. All of them have failed and those failures do reflect on Kodak (certainly on their bottom line!). But it's sure not because Kodak didn't see the world of change that they were facing. For general background on that change, read my column, "The Shape of Things That Came." On to the specifics of Kodak:

In the early 1980s, Kodak started demonstrating computer-assisted photofinishing. These were hybrid systems that involved film scanning, computer data massaging, and image writing back to traditional photographic paper. They developed and successfully incorporated these technologies into successive generations of equipment. Unfortunately, that all happened behind the scenes, so it didn't establish a market position for them. Their first real effort to grab digital name and brand recognition was the introduction of Kodak Digital Media in the mid-1980s. Unfortunately, they didn't know how to market against the real 500-pound gorillas in that arena, 3M, Sony, and Teac, the companies with existing name recognition for magnetic storage media of all sorts. Kodak was put in the unfamiliar position of being the small and new kid on the block. Their marketing simply didn't know how to deal with it.

The second attempt, in the early 1990s, was PhotoCD. The science was brilliant, the technology was good, and they understood the marketplace. Not only could they provide superior image quality in a convenient, portable form, but the "jeans" won out over the "suits" and they released PhotoCD as an open standard. Smart move!

Not-so-smart moves: the "standard" evolved over several years, and you had no assurance that later generations of Photo CD equipment would color manage early PhotoCD files correctly. That was the lesser problem. The bigger one was they screwed the economics. Kodak promised the photofinishing labs that they could develop the film and produce PhotoCDs for substantially less than a dollar a frame, making the cost per roll competitive with what one-hour labs were charging back then. That promise was never met—not even close. It was so unfulfilled the Kodak later denied making such a claim, but I heard it with my own ears, said at a PhotoCD developers' conference by a qualified Kodak executive to a group of highly skeptical lab owners.

Then there was the economic disaster that was the PhotoCD home player. They sent me one to critique (not to review) and I told them exactly how and why it was going to bomb*. By analogy: suppose you decided to manufacture an economy automobile and you decided it ought to be under $15,000? Suppose the car you built to sell for under $15,000 could only go 40 mph? In order to meet their desired market price, Kodak so badly compromised the performance and features of the home players that they were genuinely tedious to use. PhotoCD never took off in the general world, although it got huge institutional use (which is why Kodak maintained it for as long as they did).

Third big effort: Quality digital cameras. Remember that Kodak used to own that market! They produced the absolute best professional digital cameras in the world, and people lined up to pay $15,000–$30,000 for them. Kodak was the Leica+Hasselblad of that world.

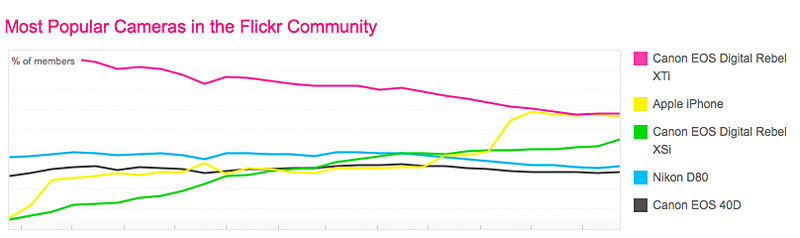

Then the perfect wave I referred to in my earlier column broke, and digital camera price/performance ratios started plummeting, far faster than most sane people would've predicted. Kodak pretty quickly realized they were in big trouble that way; they could no longer maintain those kind of prices to support what were undeniably superior cameras. So they tried their last big gamble: The DCS 14n. It was supposed to be the best DSLR out there by far, at a price/performance ratio that would leave other manufacturers gasping. Only two small problems: first they announced vaporproduct, to try to steal the thunder from Canon announcing their quality DSLR. But, Canon could deliver, while Kodak's camera was still months away. Professional photographers are even worse about deferred gratification than consumers.

And the ultimate killer: Kodak made a fatal development blunder and outsourced the sensor for the camera, to get it cheaply and quickly enough to meet their price point. Unfortunately, that sensor wasn't anywhere close to Kodak's usual quality. It was a horrible mistake from a company whose reputation had been built on the superiority of their sensors. When the DCS 14n finally reached the real world, it had only slightly better resolution than the Canon camera, despite having many more pixels, and the overall image quality was substantially worse. That was the end of Kodak's premier position in the professional camera market.

So, lots of attempts and lots of failures (I haven't even included lesser initiatives, like the Premier system or Kodak's thermal transfer printers). Some of those failures should have been seen in advance; some of them could only be seen with hindsight. But the bottom line doesn't really care why you failed, only that you did.

Make no mistake, though, these failures are not because Kodak has had a lack of will or long-term perspective on what photography is all about. To the extent that the school of hard knocks serves as any kind of a teacher for large corporations (and I don't know that it does), don't write Kodak off. They've had a hell of a lot of education beaten into their skulls over the past quarter-century.

*David Alan Jay, then the Editor of Photo Techniques, did the same, long before Ctein joined the staff of that magazine. —MJ

Send this post to a friend

Featured Comment by MBS: "Thank you for this posting. It is both interesting and good to hear.

"I think that in this, as with so many things, there is an element of evolutionary BVSR (blind variation, selective retention). And the BS part (interestingly) of that more or less insures that it is not possible to know for certain ahead of time what adaptations will still be breathing when the fat amoeba sings. An organism can be mutating like mad and yet still not make it within its local environment (of course, the greater population within photography is, in fact, finding adaptations that work, as one would expect in a robust and complex system). As much as we as individuals (and corporate entities, too) like to pat ourselves on the back over how well we were able to 'see' and meet the future, I think there is more randomness to the selection process than we are comfortable admitting. Kodak certainly has some smart people working for them, but that may not be enough. Still, the opera ain't over: the amoeba has yet to take the stage."

Featured Comment by Eamon Hickey: "My sense of this is similar to Ctein's and to those expressed by Josh in the comments.

"I was working for Nikon from 1991 through early 1999, and from that perch it was my observation that no company in the photography industry was savvy to the coming of digital anywhere near as early as Kodak. The efforts that Ctein outlines are ones I remember well (I quite well remember the PhotoCD, which first clued me in to the digital wave that was then still far over the horizon.)

"I'm sure that Kodak made many, many errors over that time, but, really, as Josh suggests, I think the basic problem for them was that this was too big a change happening too fast. The need for their core product plummeted drastically in less than a decade. Who could manage that crisis smoothly?

"Same for Polaroid. Great company; highly profitable for decades. Gone in less than a decade. Sure, their management made many mistakes, but they had a huge bottom line problem: their product just wasn't needed any more."

Featured Comment by Ken Tanaka: "I have to disagree with the remark from 'MBS,' 'Still, the opera ain't over: the amoeba has yet to take the stage.' Yeah, it basically is. If you're going to use life/science metaphors here, Kodak's energy source is evaporating...specifically, its capital value. While EK is riding a bit of the same wave currently moving through the equities markets it's merely a floater. It has sold enough stock to paper the planet and still has a total market cap of just over $1 billion. But its stock has traded below $8 for the past year and at this writing closed at $4.67. Kodak's latest significant desperate move was to suspend their dividends after the fall of 2008. This was something of a death knell for many investors, since EK spent most of the past century as a dividend-paying large-cap value stock.

"Kodak is now firmly categorized as a 'distressed' stock in the investment world, very few members of which have any confidence that they can pull out of their descent into oblivion. They're only barely (and mostly only internally) considered to be any part of the new world of imaging by the capital markets. Most of the investment interest in EK comes from vultures waiting for opportunities to feed on its parts.

"The 'smart people' on Kodak's payroll are utterly irrelevant in the wake of so many poor and delusional management decisions over the past 20 years. Yes, Kodak is making some good products here and there. But they're breathing the air in their long-buried coffin.

"As 'bobdales' so succinctly observed earlier, 'Dead man walking.' Yup."

(Prior to devoting his time to art and photography, Ken spent many years toiling in various parts of the institutional investment management world. —Ed.)