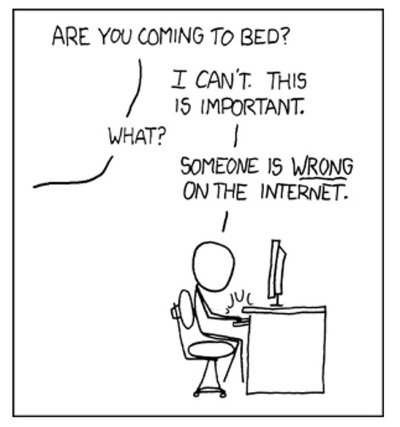

I have a sardonic little mantra I like to repeat that goes "editors needed everywhere." It's a response to encountering "howlers" in the wild—a "howler" being an error so egregious that it makes you howl (whether in amusement or in pain remains unspecified). I even have a friend (hi there, Paul) with whom I share particularly woeful or wonderful typos and examples of ungrammatical English.

Here's a recent example (I think I found this one)—

This is an attempt to compare the performance of the PhaseOne digital back with the one obtained by scanning a low-sensibility film picture from 6x9 format.

Paul and I agreed that we can sympathize, because both of us have taken plenty of low-sensibility pictures over the years.

Anyway, as you might know, recently I've been watching some movies again. This follows a period of more than ten years when I hardly watched any at all—I virtually only saw movies that friends took me to see as part of a social occasion.

A recent article about the cynicism of Hollywood noted that Hollywood now "targets" movies at specific demographic segments—young males, young females, older females, or older males. The point was made that if you can appeal to more than one of those demographic groups, it's generally a good thing, but if you target only older males, you're sunk, because older males don't go to movies.

Once I read that, I figured my behavior might simply be typical for my demographic.

I think it's more complicated than that, however. I think I reached a point a number of years back where Hollywood had simply let me down.

The reason is, I hate getting jerked around.

And "jerking people around" is virtually a mission statement for the movie industry. That's what they're trying for. Striving mightily to overdo everything. Everything has to be over the top, turned up to 11, overcooked, on steroids, enhanced—and that includes shamelessly and blatantly manipulating the emotions of the audience.

I just don't like being treated that way.

The most recent two movies I've watched brought that point home again. The first was "Blood Simple," the Coen brothers' first movie. It's a neo-noir thriller, and expertly plotted—I loved the basic plotting device, which is that every character misinterprets what's actually happening and acts perfectly logically according to what they believe is going on—all the way down to the delightful ending, which I won't give away. (Where she says, "I'm not scared of you [blank]....")

It has a superb score, too, by Carter Burwell, one of the best I've ever encountered in any movie. It's both extremely subtle and extremely distinctive, which is like hitting two home runs with one swing.

But of course it's a "thriller," which implies a standard packet of audience manipulations: most especially, characters must spend a lot of time standing around stupidly doing nothing when danger is imminent or something bad is about to happen to them. People in thrillers act slowly so audiences have plenty of time to squirm. Apparently people like that.

I don't.

I want people to act naturalistically, i.e., like real people would act.

But "Blood Simple" is a good movie and well worth seeing. Its disappointments are nothing compared to the 2003 "House of Sand and Fog," adapted from the novel by Andre Dubus III, who is responsible for the plot.

First of all, "spoiler alert," although if I spoil this movie for you I will have done you a favor.

My first reaction was that this was a horrible movie, really one of the worst I've ever seen. I literally took the DVD out of the machine, put it back in its case, and threw it in the trash. Sorry I watched it, wish I hadn't. (This amused me: Andrew O'Hehir, writing in Salon, said "After the New York screening I attended, a middle-aged couple coming out the door ahead of me were complaining bitterly about all the things they could have been doing instead of watching 'House of Sand and Fog.' Their list included watching 'Law & Order' reruns on TNT or shopping for their kids at Toys 'R Us; it's safe to say these folks were unhappy campers.")

I might be a little out of step, too: many reviewers apparently thought the director was trying to make the American characters sympathetic, whereas I thought the movie was deliberately trying to make Americans look bad. If that woman and that cop are sympathetic, I'd sure hate to see what passes for unsympathic.

It wasn't until the day after I watched the DVD that I realized what's special about it: it's a movie that fails utterly, but only because of its story line. Bad writing sinks the whole enterprise.

Well, and its score, which is also awful. It was driving me crazy by the end. But mostly the story line.

Everything else about the movie, though, was oustanding. Usually, great movies succeed on many levels, but they tend to hit on all cylinders. That is, all the different contributors' elements—acting, directing, casting, writing, cinematography, etc.—all work together, in concert. Bad movies usually fail in more than one area—everything's vaguely off, or bad, or weak, or doesn't gel. Sometimes, passable movies have flaws they can't overcome, but mostly, the flaws are multivalent.

Jennifer Connelly in "House of Sand and Fog."

Jennifer Connelly in "House of Sand and Fog."

But it's unusual, I think, to find a movie that succeeds in essentially every way except for its writing. "House of Sand and Fog" is very well crafted in many ways, from its inventive premise (Dubus also gets credit for this) to its casting. I bought it because Roger Deakins did the cinematography, and the cinematography is excellent. I could quibble with the casting of Jennifer Connelly—I thought she was too pretty for her role—but she gives a fine performance. The acting is excellent overall; the film even delivers one standout acting performance, from Ben Kingsley, and a very strong supporting performance by the ex-patriate Persian (Iranian) actress Shohreh Aghdashloo.

But the writing at the end. Ach.

One of the problems novelists have is that they're almost fatally tempted to act as puppetmasters. They own their characters, and they can make their characters do anything, anything at all, and frequently they're just unable to resist that temptation (read virtually any John Irving novel to see this flaw taken to an extreme—that guy really makes the puppets dance).

Two-thirds of the way into this story, the writer is in full-on puppeteer mode. We depart completely from rational, naturalistic human behavior and devolve completely into Hollywood mannerism. The last third of the movie, by which time a subtle and inventive premise has imploded utterly into a standard bad-TV-style hostage-and-gunpoint melodrama, complete with not one but two suicide attempts in less than ten minutes, the story line has become 100% certified fake-serious. And how does Hollywood fake seriousness? Like you need me to tell you that. Blood, gore, and premature death, obviously. (It made me laugh a few years ago when I first saw the title "There Will Be Blood." What was that, a scribbled instruction from a producer? A chapter from How to Write a Modern Screenplay? Too funny.)

Guns, blood, death, gore, and more death is the default mode of signifying depth in American art.

Although a rogue cop acting like a complete unhinged idiot never hurts*.

This one goes for Hamlet-level everybody-kill-yourself. The writer must have thought, I'm going to make this real estate squabble really, really serious, boy. You watch, everybody's going to die or have their lives ruined.

Rub hands together. Cue actors.

Gee whiz. Guess this must be Serious Dramar, then.

Piffle. I've gotten a lot of pleasure over the years from many of my encounters with art, but some of them you just wish you could take back.

Anyway, the hopelessly bathetic "House of Sand and Fog" is a fine example of the reason I stopped watching movies. It was not because I was enacting my demographic: it was because...well: writers needed everywhere.

Mike

"Open Mike" is a series of off-topic posts that usually appear on TOP on Sundays. Disclaimer: the writer is not a professional movie reviewer, knows no Hollywood writers except Gordon Lewis, virtually never watches pop schlock, and has seen far fewer movies than the average American. Season accordingly with grain of salt.

*I might have to cut this movie and TV stereotype a little more slack in the future, however. In 2007 a sheriff's deputy here in Wisconsin shot six people, including his ex-girlfriend, at a party. So it does happen. Is it still fair to say that most officers of the law would not attempt to compel real estate transactions at gunpoint?

Send this post to a friend

Please help support TOP by patronizing our sponsors B&H Photo and Amazon

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2011 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

Featured Comment by David: "As it happens, I am both a regular TOP reader and a Hollywood screenwriter.

"One of the many pitfalls of my profession is that when people love a movie, they praise the acting, the cinematography, and—most of all—the director. When people hate a movie, they blame the screenwriter.

"The contempt that is leveled at screenwriters is reflective of two attitudes: the belief that writing is easy, and a complete lack of understanding about how the creative process works in Hollywood.

"The screenplay is the battleground of moviemaking. A writer creates a screenplay that is strong enough to pull together the 'elements'—the director, actors, and financing. Then it becomes the object of endless negotiations, power plays, wrangling and tweaking by executives and producers which frequently serve to dilute or destroy any fragile shred of coherence in the final product. After a few rounds of this, the script is usually a mess. Then the 'damage control' begins as the start date approaches, torturing the poor thing further. When it's all over, the executives get to pat themselves on the back for 'saving' the movie, or, if it's a failure, they get to blame the writer. As a general rule, when you watch a Hollywood movie, it's usually much, much worse than the first draft that begat it.

"I imagine it's hard for you to relate because you are in a business where you work alone and enjoy complete control over your product. That's feasible when that product costs close to nothing. When the artwork in question costs $80 million and involves major multinational corporations with many layers of bureaucracy, it's a very different process. Even editing a photo magazine as you once did really gives you no frame of reference for what goes on in this ecosystem. Photography is fairly simple. That's why I like it.

"If you were a writer in Hollywood and had any understanding of what goes into making movies—and believe it or not, most writers in Hollywood are very much like you—you would reserve your contempt for people other than your writing brethren."

Mike replies: Thanks for the great comment—always best to hear things like this firsthand—but I think you've misread me a bit. I'm aware of the realities, at least at a couple of removes—I've read things like John Gregory Dunne's Monster and I used to have a passing acquaintance with Larry McMurtry back when he was making a good bit of his living writing treatments. And I recall that vivid image in "Adaptation" where one of the great artists in Hollywood, Charlie Kaufman (or rather the "serious Charlie" character he wrote), is reduced to lurking in the shadows of a movie set, just to be at hand in case the director might need him. Outrageous. Like Shakespeare serving at the pleasure of Shylock.

It's not really "the writer" I'm excoriating here but "the writing"—not the original script but the story of the movie as it was made. As a critic, I have to deal with the work of art that's in front of me—I can't deal with phantoms of what should have been or might have been.

I wish I could find for you an impassioned essay I once write in defense of screenwriters, condemning the system that can literally rob them of their stories, and in more ways than one. Lost, unfortunately. Suffice it to say that I think the "mess" you mention ("After a few rounds of this, the script is usually a mess") is discernible to at least some degree in virtually all of Hollywood's product—to its detriment. At the very least, I'll just mention that the contrast between plays and films could hardly be more instructive. Just imagine a staging of a Eugene O'Neill or Arthur Miller or Tennessee Williams play where the producers called in three additional writers, changed a majority of the dialogue, changed the story line, recast the entire ending, and relegated the original playwright to uncredited status. ("I want a rewrite on Murder In the Cathedral and I want it by Tuesday!" "Dear Mr. Simon, we like Lost in Yonkers, but does it have to be Yonkers? It makes us think of honkers.") Inconceivable. Hollywood's refusal to respect its best writers and accord them some of the same status that playwrights receive is its #1 failing, in my opinion—bar none.

In fact, my feeling is that the only way screenwriters can get adequate respect these days is when the screenwriter is also the director—one and the same—as is the case with the Coens. (I was astonished recently when I read something about Joel Coen objecting when his leading actor changed one word in one of his movies—he insisted on having it exactly the way it was written. What other screenwriter would get that kind of respect from any director?) But I don't really have enough knowledge to make that claim. I'd love to hear your take on that.

Response from David: "Thanks for your reply, and sorry if I might have sounded a bit prickly. The answer to your question is: you're right.

"Directing is one way of staying in control of your product, but it's hardly a guarantee. On big studio 'tentpoles,' as they're called, the director is often as much at the mercy of the system as the writer, though they are more careful to maintain the illusion that they're in control.

"Even directors need someone who can insulate and protect them. A good producer—and they are very rare—can shepherd a project through the system while protecting what makes it unique. You'll notice that the Coens work almost exclusively with Scott Rudin, who keeps the outside forces at bay so that they can do their thing.

"These days, the best vehicle for writers has been television, where the creator or 'showrunner' enjoys a level of control that is unparalleled in movies. A writer like Matt Weiner of 'Mad Men' controls every camera angle, every line reading, the placement of every prop. He has the leverage of being the only guy who can put the show on the air every week, so he can do anything he wants.

"The truth is that it's very difficult to gain the kind of control the Coens have, and even harder to keep it. They get it because they're so good at what they do, and because they literally refuse to show up unless they get it. It's not just that they don't compromise, but that they don't even understand compromise. They resemble autistics in that they are so narrowly focused on their vision that nothing else even enters their consciousness. But their style of filmmaking is the exception, not the rule. Most studios would not be interested in dealing with them at all.

"Those of us who do this for a living are never surprised when we see bad movies. We watch bad movies and see the endless procession of meetings and memos that led to their creation.

"What's surprising—almost miraculous—is that every year one or two good movies manage to get through the system and make it into theaters, and those movies are what keep us going."

Featured Comment by Paul Byrnes: "Try watching movies for a living, Mike. Lots of people think it's a breeze but after spending most of my adult life doing it, I share some of your pain. Being jerked around is my daily duty. Recent peak: standing in the drizzle outside a movie funpark in southern Queensland on a Sunday morning waiting for my chance to see Yogi Bear in 3D, a character most of the kids present had never heard of (I asked a bunch of them).

"That said, I'm glad you didn't give up—then the bad guys win. There are still lots of great movies being made, even some in Hollywood—or just north of there, especially at Pixar. And you might like to delve into the hard-to-find works of Yasujiro Ozu, one of the greatest Japanese directors, from the 1930s to the 1960s. He eschewed plot—'plot uses people.' The smallest human interactions produced the most beautiful human dramas in his films—and he shot everything from one position three feet above the ground, the height of the head when one sits on a tatami mat. No camera movement either, the tripod was locked off. Try 'Tokyo Story.' A great antidote to modern unsteadicam techniques.

"Looking forward to your post about movies about photographers. I'm compiling a list of the cameras they used, for my own amusement—like the Argus C3 that Ruth Hussey uses in 'The Philadelphia Story,' or the Nikon F's that Clint used in 'Bridges of Madison County.'"

Mike replies: I grew up watching Yogi Bear in black-and-white. I still distinctly remember seeing Yogi in color for the first time—I was very critical, because I was convinced they got some of the colors wrong. I was six.

Featured Comment by Edie Howe: "It's been years since I've made the effort to go to a movie of my own volition. Like you, I too dislike the emotional roller-coaster of scripted movies. With all due respect to sibling TOP reader David, there is little to engage me. (Side note: Google "Bechdel test" for further explanation.)

"That said, might I suggest non-verbal, non-narrative films? As a photographer, I find myself fascinated with this form of film-making. I have this urgent feeling that cinematography has an important role in a photographers education, and since meeting Tom Lowe (Timescapes.org), I've been exploring the genre with deep interest.

"Check out Baraka from Netflix, or peruse this incredible teaser/trailer by Tom Lowe for stunning examples.

"Now for my own disclaimer: I know Tom and consider him a friend, and have acted as ad hoc location scout for him here in Yosemite."

Featured Comment by Paul W. Luscher: "Actually, there is one more way of 'signifying depth in American art': kinky sex. I.e., 'Black Swan.'"