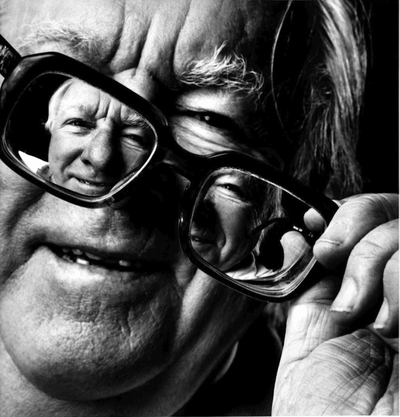

By Ctein

By Ctein

Introduction: Mike's recommendation of some philosophy books a few weeks back caught me by amused surprise. This seems to be yet another case of great minds lying in the same gutter, because while he was writing that column I was laying out this one.

I don't read anywhere as much as I'd like. I still buy a few more books each year than I find time to read. There are close to 600 unread books on my shelves, 400 of which fall into the "I really must read this" category. Consequently, I almost never go back and reread a book.

Mostly I read for entertainment, occasionally for factual education. On very, very rare occasions, a book comes along that actually makes me think. They are few and far between, and I'm recommending five to you. It happens that three were written by friends of mine. I won't tell you which ones. Don't ask. It doesn't really matter. I have hundreds of books written by friends on my shelves; I'm not recommending most of them.

If you read all of these, at least one of them will make you think very, very hard about stuff you thought you already knew. Probably, all of them will.

It's almost impossible for a thought-provoking book to be anything but controversial. We don't want to engage those controversies here. Were I to recommend a book on economics, that would not be a call to debate capitalism vs. communism. Not that Mike would allow it, but let's make his life easier and keep the conversation meta, okay? So, without further ado:

1

Beyond Fear: Thinking Sensibly About Security in an Uncertain World , by Bruce Schneier

, by Bruce Schneier

Bruce is such a well-known security/computer security expert that XKCD makes jokes about him in its rollovers. The book's subtitle, "Thinking sensibly about security in an uncertain world," sums it up. It's a straightforward and common-sense discussion of real world matters, things that affect us every day. More important, it's a tutorial on how to think about security. That's its major value.

For example, there is threat vs. risk, concepts that people conflate. Threat is what might happen to you, risk is how likely it is to happen. Your security usually involves reducing risk to manageable levels, not necessarily eliminating threats. That's on page 20 of nearly 300. It just gets better and better.

2

God's Mechanics: How Scientists and Engineers Make Sense of Religion , by Bro. Guy Consolmagno, S.J.

, by Bro. Guy Consolmagno, S.J.

Brother Guy is an MIT-trained astronomer who got the calling in midlife, became a Jesuit brother, and now works for the Vatican (his specialty is meteors and and other subplanetary bodies). He's a consummate techie who is also profoundly religious. This isn't as fringey as you might imagine; a substantial percentage of scientists and engineers are religious. He got curious about how other techies deal with their religious beliefs, so he studied them.

The first third of the book presents historical background on science and religion. He shows how good/bad theology has lead to good/bad science and vice versa. Did you know that Kepler came up with his famous laws of planetary motion because he believed that the Godhead physically resided in the Sun and so the Sun must be at the center of the motion of all stellar bodies? Great science but lousy theology. He also elegantly explains why trying to use science to validate theology is a terrible strategy.

The second third is a field study; Guy talked to about two dozen techies, questioning them on exactly how and why they were involved with religion and wrote up their case histories for our benefit. Fascinating stuff, and the truly original part of this book.

The last third homes in on Guy's relationship, as a techie, to Christianity and the Church. Roman Catholicism has less-than-zero appeal to me (yes, I am religious; no, it's none of your business) but when I was done reading this section I had a genuine appreciation and empathy for how it does work for Guy.

3

Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity by Julia Serano

by Julia Serano

I'm not sure how to convince most of you to read this book: a collection of essays of radical feminist political theory by a trans woman. Very much my cup of tea, not most of yours. So, why do I imagine most of you would get anything out of this book? Because this book presents a brilliantly integrated and extensive model of gender and sexuality. It was recommended to me by a respected friend, Marlene Hoeber, and to steal some of her words, this is the unified field theory of sex and gender. Marlene wrote, "Serano is a scientist in her primary career and it shows in this work. Her suggested structure fits the available evidence without stretching or omitting data. It is a workable operational model that is not worried about unknown causes."

As such, it doesn't demand redefining who you are, as too much hortatory political theory does. Think of it like this: Newtonian physics works perfectly well for a lot of everyday things. But when you're stuck with puzzles and seeming paradoxes (the constancy of the speed of light, the ultraviolet catastrophe, etc.) then you bring in quantum mechanics and general relativity. An understanding of those gives you a comprehensive and practical insight into the world.

Similarly, Juliana replaces the simplistic one- and two-dimensional models of human gender with something that's much more complete and actually makes sense in light of the way humans act, instead of prescribing how they should act.

I thought I had a really good understanding of gender before I read this book. Boy, did it ever prove me wrong.

4

Dr. Tatiana's Sex Advice to All Creation: The Definitive Guide to the Evolutionary Biology of Sex , by Olivia Judson

, by Olivia Judson

Now we turn to the lighter side of gender, namely sex! Humorous and entertaining, yet fact-filled, this book is cast in the form of an advice column to the lovelorn, viz.:

Dear Dr. Tatiana, we're sea hares. We've been having a fabulous orgy—being both male and female we all get to play both roles at once. [...] It's such a great system, so much better than being male or female, that we're mystified why everyone hasn't followed our lead. Why aren't all living things hermaphrodites?—(signed) Group Sexists in Santa Catalina

It's fun, it's funny, it's damned educational. Judson is an evolutionary biologist, a breed that has justifiably gotten a bit of a bad reputation. Too many of them took their marching orders from the Social Darwinists, picking and choosing their data and their logic to justify the status quo. The results were as reliably laughably idiotic as they were intellectually dishonest. (My favorite example from the seventies was a claim, made in all seriousness, that women had large breasts because that body type had been selected for by men. A theory that manages to ignore the huge variation in standards of beauty across space and time, as well as the undeniable fact that there is a more-than-sufficient subset of the male population who are simply horndogs and will, as the song lyrics say, "love the one they're with.")

Olivia is not of that ilk. She manages to explode, discredit and disprove so many prevalent myths about sex and sexuality across the animal kingdom, using established scientific information. It's a real hoot.

5

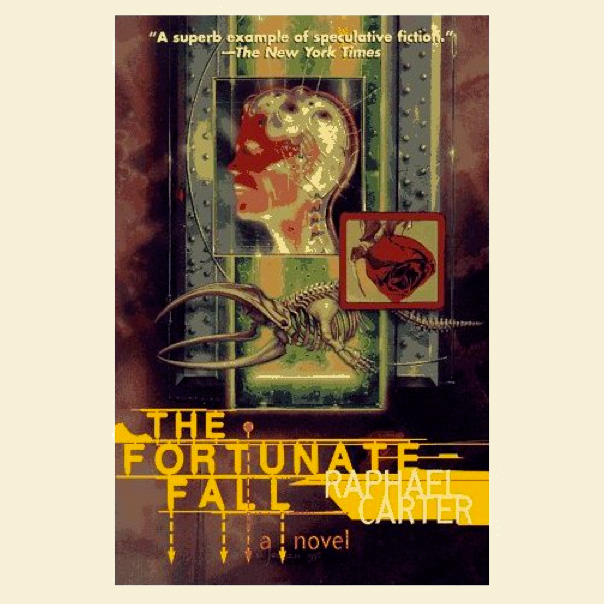

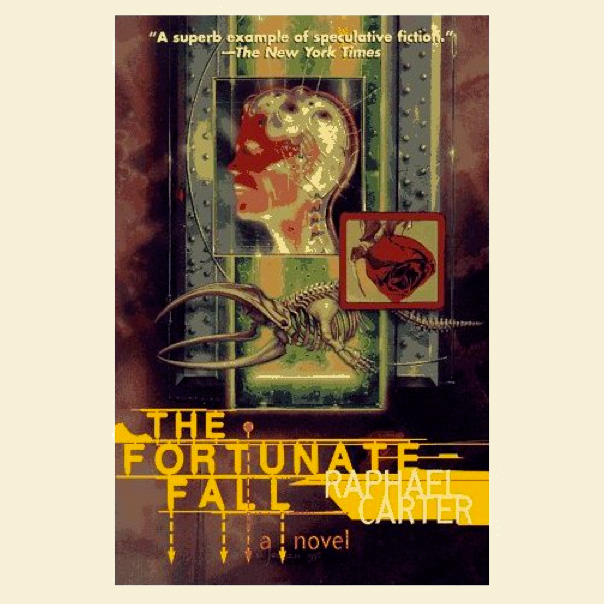

The Fortunate Fall, by Raphael Carter

This one is science fiction, unfortunately out-of-print, but readily available used from Amazon . [UPDATE 6:00 p.m.: The clean and reasonably priced ones seem to be gone now, apparently due to attention from TOP (there were plenty this morning when I checked). Sorry about that. Perhaps check abebooks.com or your local library system? —Ed.]

. [UPDATE 6:00 p.m.: The clean and reasonably priced ones seem to be gone now, apparently due to attention from TOP (there were plenty this morning when I checked). Sorry about that. Perhaps check abebooks.com or your local library system? —Ed.]

It's vaguely on-topic (and I do mean vaguely); the protagonist is a living camera, a journalist of the future when everyone and everything is wired. And like all good journalists in novels, she stumbles upon a conspiracy and cover-up and starts to pursue the truth behind it. I don't want to tell you any more. It would spoil the fun.

For one thing, I couldn't figure out what this book was up to until I was well over 100 pages into it. I can usually divine an author's broad intentions within a chapter or so. Not the plot details of course, but the broad thematic skeleton the author will flesh out with story. In this case, I just couldn't figure out Raphael's skeleton. The book was in no way obscure; it was so rich with possibilities and directions in which it could go that I really didn't know which way she was going.

That's high praise. This books deserves it; it is one of the very best first novels I've ever read.

Let me tell you something else about this book. When I got to the end, I said to myself, "Huh." And I turned back to page one and started reading it all over again, for the pleasure of truly appreciating and understanding all the details in the book in their larger context.

I have never, ever done that with any other book, fiction or nonfiction. As I said at the beginning, I rarely read anything more than once, ever, let alone twice in a row.

The book is that good.

Ctein

Ctein's columns, one out of four of which are off-topic, appear on TOP on Wednesdays.

Send this post to a friend

Please help support TOP by patronizing our sponsors B&H Photo and Amazon

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2012 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

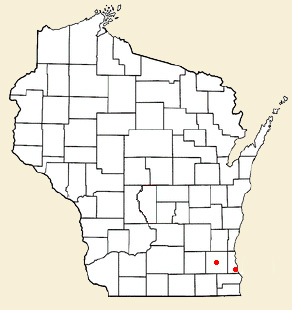

The red dot on the left is TOP World Headquarters. The dot on the right is the scene of this morning's Sikh Temple shooting.

The red dot on the left is TOP World Headquarters. The dot on the right is the scene of this morning's Sikh Temple shooting.