...Or, "Sometimes it's not so simple." :-)

The basic rule of thumb I put forth in Part I of this article—to use the three middle apertures to get the best optical quality from your lens, whatever that range happens to be for the particular format you choose to use—was one of the very first things I learned in photography. My father gave me a Konica Autoreflex T3 for my 16th birthday, and the T3 had shutter-priority AE—you set the shutter speed with the shutter-speed dial and the camera set the aperture itself according to its meter reading. The viewfinder featured an indicator needle protruding in from one side and a vertical row of apparently meaningless (to me) aperture numbers. I just didn't know where the needle ought to be. My father had a professional photographer friend, the late Arnie Gore, and Arnie told me to keep the needle in the middle—to make the needle fall on the eight, if possible, or one number on either side of it, except when the shutter speed got down below 1/30th. Useful advice for a novice like I was at the time. I followed it for years.

Of course, as you might know, there are situations when "use the middle apertures" isn't optimal advice.

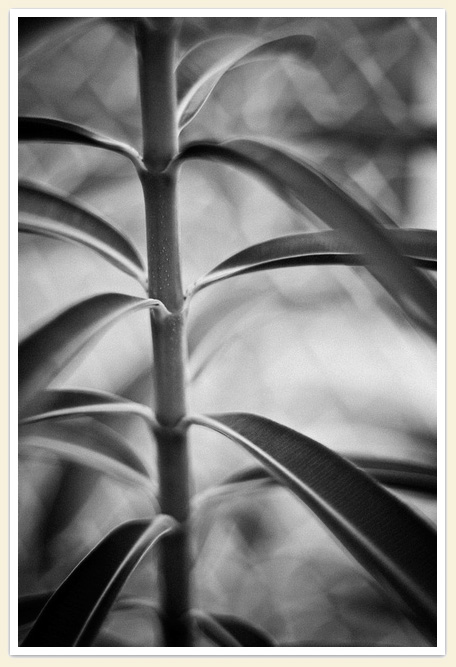

The first, most compelling reason is if you're doing some sort of specialty work. Portraits seldom look best when the lens is well stopped down; you'll usually want to experiment with wider apertures for portraits. At the other extreme, macro work often requires smaller apertures because depth-of-field is related to subject distance—the closer you are to what you're photographing, the less depth-of-field there appears to be. So macro photographers often stop down more. These are just two examples. There are many more such situations.

Next in importance is when you'd seeking specific visual effects that you think a particular picture needs. Two examples might be shooting wide open to get lots of bokeh and characterful aberrations, or stopping down more to get more of a scene in focus front-to-back.

Those two things have a heavy degree of overlap, of course. When a fashion photographer routinely photographs models on 35mm or full-frame digital with a 300mm lens wide open, it qualifies as both a specialty application and as a desire for a certain "look."

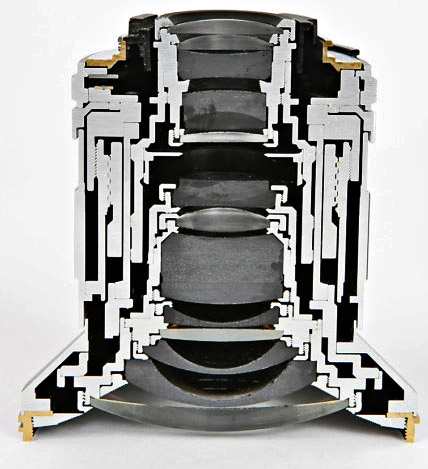

But purely in optical terms, too, different lenses are different.

For one thing, slower lenses usually clean up faster than faster lenses, for a given focal length. A 50mm ƒ/2.8 macro lens might reach its optimum and be diffraction limited* one and a half stops down, whereas a 50mm ƒ/1.4 lens might not clean up adequately until you reach ƒ/5.6—four stops. Which puts the lie to the old rule that you should stop your lens down "two or three stops" for the best results. Usually that advice works—just not always.

Almost no lenses are "diffraction limited,"** per se, but I did use a Leica 90mm ƒ/2.8 M lens once that reached optimum performance one stop down. And it was very good wide open. A lens like that can effectively be used at any aperture, with different apertures preferred only on the basis of your desired depth of field.

Then there are those dogs that just suck at every aperture. Fortunately, those are becoming much more rare these days too, as computer-aided design has become the norm and quality control has become mostly a solved problem. To the extent that some lenses are still of poorer quality than the best ones, that property can be said to be partly "designed in"—usually, of course, in the pursuit of cheaper selling prices.

Lenses of radically different focal length will have different characteristics as regards the usability of various apertures.

Even the very best lenses are still a mass of compromise and limitation. One very highly corrected lens I used once—it was a 100mm Zeiss Hasselblad lens —had a decidedly pentagonal aperture shape and alarmingly poor bokeh. Out-of-focus foliage was a bizarre sea of bright pentagons! So much for perfection; there's really no such thing as a perfect lens. (Just maybe one that's perfect for you.)

Know your apertures

The best thing, of course, is to know your lenses. I've always advocated using as few lenses as you possibly can—four at most, two ideally, and one if you're hard-core. One reason is that the fewer lenses you use, the better you'll get to know them.

I do sypathize with zoom lens users, who have an exponentially tougher time getting to know their lenses, because they have two variables to contend with instead of just one. With fixed-focal-length lenses, which I prefer, all you have to do is learn how the lens behaves at each aperture. With a zoom, you have to learn each aperture at each focal length. No wonder many casual amateurs and occasional photographers never do learn what's going on.

How a lens performs wide open and where it reaches a practical optimum can be important considerations. One of the better lenses I ever used was the tiny Fujinon 60mm in the Fuji GF645s. Unfortunately, the full stop or widest aperture was useless because its optical quality was so poor at that aperture. It really needed to be closed down one stop—two was better—to be used. Because it was a slow ƒ/4 lens, this was a serious limitation. I ended up using that camera a lot on a tripod—which was somewhat conceptually dissonant, since the camera was a small, portable rangefinder. The lens sure was beautiful at ƒ/8 and ƒ/11, though.

Note, too, that when I say a lens is optically best at its middle aperture, I'm not just talking about the point where it reaches highest certer resolution. Remember what I said last time: "A lens image is always a balance of many properties. Always." So center resolution might be best at ƒ/4, but is falloff? Is corner sharpness? Is evenness across the field? That magic middle aperture is just where the best balance of all qualities occurs.

As ever, being ever the empiricist, I'd advise you to learn your lens by looking. Now that pixel-peeping on our monitors is so easy, it's not a lot of work to shoot some scenes "up and down the aperture range" and simply look at the results. Don't get anal about this or that property—the absolute resolution in the center of the field or the precise qualities of the bokeh. Just look at examples and see what you like and don't like, what's acceptable to you and what isn't. You'll eventually get a feel for where the problems are showing up visually, and thus you'll begin to know when you'll want to use certain apertures or avoid others.

I groused the other day about how all cameras seem to be getting "good enough" these days. (Only a dyed-in-the-wool gearhead could grouse about such a thing!) But no matter how good lenses get, a really fine lens can still justifiably be a photographer's prize possession. And a lens you know well is almost always finer than one you don't, when it comes down to pictures.

Mike

*The term denotes the point in the aperture range at which diffraction becomes the aberration that degrades the picture the most. At wider apertures, other aberrations predominate and overwhelm the smaller effects of diffraction.

**When the lens itself is said to be diffraction limited, it means it's diffraction limited when wide open. These lenses do exist, but they're very rare, especially among consumer lenses for pictorial photography.

Send this post to a friend

Please help support TOP by patronizing our sponsors B&H Photo and Amazon

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2011 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

Featured Comment by marcin wuu: Speaking of Autoreflex—Mike, I think you might find this image to your liking (it's of my son, as of now age 7):

"(And, in reference one of your previous articles, it was shot with sony A850—the best digital 35mm camera, save the A900 ofcourse :))"

Mike replies: Only cool kids shoot Konica!

arrived here at TOP World Headquarters (a.k.a. my house) yesterday. It's a lovely little thing, seeming somehow tinier than the 40mm pancake because it's so much narrower, even though of course it's longer. The silent autofocus is almost disconcerting at first, if you're not used to it, but fits the lens's premium/luxe gestalt. The lens is at least so small and light that it will be a burden to no one's camera bag to carry it.