Waukesha*, Wisconsin, June 2011 — I'm 54 this year, and film photography has certainly come a long way since I first seriously caught the photography bug in 1980. It used to be all there was. Up until the 1990s, the technology of photography hadn't really changed in its essence in a century and a half—although of course there had been a lot of improvements and refinements, mostly, although not exclusively, for the sake of convenience.

For the past ten or fifteen years, a period of time known as the Digital Transition, there's been a great deal of status anxiety among photographers. Early on—and sometimes lingering still—digital proponents were touchy about the initially inferior status of digital imaging—or simply the fact that it was the newcomer on the scene. Next, in the early aughts, came a phase in which many people were obsessed with comparing film to digital and arguing about the results. During this phase we saw a lot of grand pronouncements as people recounted their investigations and their reasoning and proclaimed they were sticking with film or switching to digital. Lately, it's been film (a.k.a. "analog") aficionados who have been on the defensive, as digital has decisively taken over the market and removed just about any real practical necessity to use film at all.

Although a lot of film is still sold on an absolute basis, sales are constricting all the time, and the new camera market has shifted over almost entirely to digital. As of this writing there are only a relative handful of film cameras available new, and many of those are essentially vestigial. Some are being sold out of what's called "New Old Stock" (NOS), meaning product already manufactured which is being sold out of existing inventory. When that inventory's gone, a number of those cameras won't be manufactured again. You can still buy the Canon EOS 1v and the Nikon F6 new, for instance, but it's highly unlikely that either company will manufacture another run of either of those cameras, and there certainly won't be successors. (At the moment there are clear signs, including the ever-rising price**, that Nikon is reaching the end of its stock of the F6.)

new, for instance, but it's highly unlikely that either company will manufacture another run of either of those cameras, and there certainly won't be successors. (At the moment there are clear signs, including the ever-rising price**, that Nikon is reaching the end of its stock of the F6.)

Also, the quality of digital has now in some ways greatly eclipsed film. I distinctly remember in about 2001 or 2002 talking to a professional photographer who said he was happy with digital at base sensitivity (widely, but incorrectly, called "ISO"), but that he wasn't going to switch until digital could at least match the sensitivity of higher-ISO films. Obviously, digital has now gone so far past film in this regard that digital photographers regularly complain about sensitivities that were never anything but pipe dreams to film users.

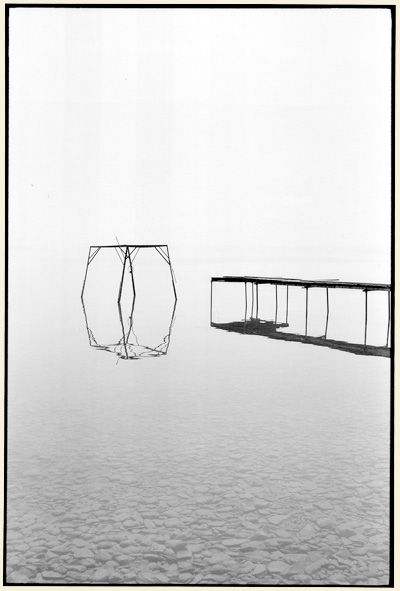

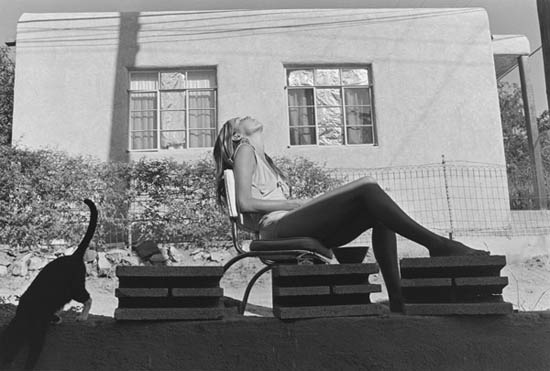

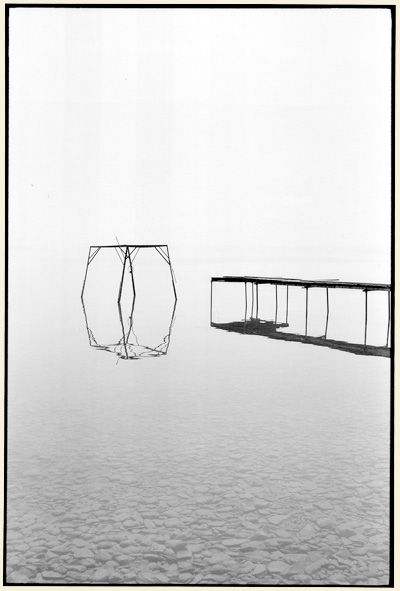

Cuyahoga, from a print made on a now-extinct Kodak paper

There are still a few actual, real advantages to film, which we'll get to eventually. But, for the most part, digital has it all over film—it's greatly more convenient, much more widespread, and for the most part, looks as good or better, especially in color.

My first suggestion is going to be that you completely ignore status issues. We primates just love to split up into groups and compete—it's just how we're wired—but there's no reason for it where photography is concerned. I'm a digital photographer, and you probably are too. There's nothing wrong with that. Similarly, there's absolutely no reason you "have" to get into film, now or ever, for any reason. If you don't want to, don't, and don't worry about it for a second. There's absolutely no reason to.

Crafts are fun

So why would you get into film photography, then? I think there's one basic reason: because it's a highly developed, beautiful craft, and crafts can be fun.

People love all sorts of crafts that are absolutely not necessary for their security or prosperity. Some people buy old cars and restore them to better-than-original condition or cobble together their own hot-rod creations. Some people love to build plastic models. People knit their own scarfs and sweaters and sew their own clothes. There's no reason you have to stencil borders on your walls, make jewelery, tie flies, or build your own furniture (is woodworking the king of crafts?). Yet people do all these things. Some people build their own electronics, soldering parts on circuit boards. Speaker-building is a thriving subculture in audio circles, even though 95% of the home-built (well, let's say owner-designed) speakers I've heard don't sound quite as good as the better store-bought ones. A photographer I know of in Kentucky teaches at a craft center where they also teach glass-blowing, which is not a skill that's of much practical use in modern life. My aunt Mary, in her basement workshop, used to make the most beautiful rustic chairs from branches she collected in the forest. I have a friend who designs and makes stained glass panels for windows and doors and such. She has recently moved over into making "pictures" by quilting together pieces made of all sorts of different fabrics. Gardening is another activity I'd put into this general broad category. Although in some sense practical, it's a hobby, an enthusiasm, and it can be very creative—although, since you're dealing with living things, it has a nurturing component that is pretty unique. You might not agree that it's strictly a craft. Still, what it has in common with all these other things is that people do it because they love it, not because they have to.

Practiced at the highest level by the very best craftspeople, almost all crafts can become art. But that's seldom the point for the majority of people.

With all crafts, there are practical byproducts. You do make things. Sometimes you can sell them. Often you can use the things you make yourself, in your own home and in your own life. But the real reward is in the doing. We do most crafts because we love the process—it's gratifying. We get satisfaction from it.

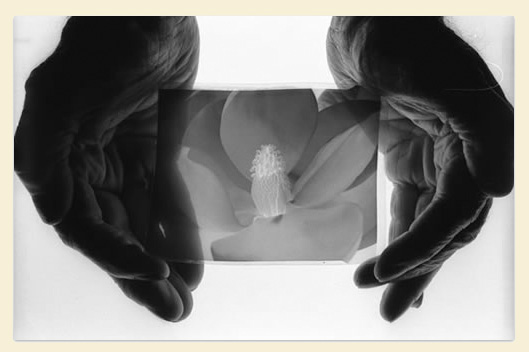

That's the extent of what I'm going to claim for classic photographic printmaking. It's a craft—still viable, lately becoming much more esoteric than previously—and, practiced as such, it can be fun and gratifying...its own reward.

Who needs to throw a pot?

In a sense, this restores photographic printmaking to a place where it ought to have been all along. When I taught photography in the 1980s, there was this pervasive sense in the air that the kids were learning skills that could well lead to paying work later on. I was asked to speak at a high school recently, and the teacher asked that I talk to the kids about careers. This, despite the fact that even many well-established photographers have trouble making significant incomes and that the supply of skilled and often inspired photographers already greatly exceeds the demand. (I once knew a professional studio advertising photographer named Toby who devised his own personal rules for living. Toby's Commandments were: "Do good, be kind, have courage, and don't be a goddamned professional photographer.") When I taught high school, I was once grilled about whether the skills I was teaching would be useful to professionals...by the ceramics instructor! What? My feeling then as now was, why should photographic printmaking be any different than learning how to throw pots? When was the last time a high school student desperately needed to be able to make her own coffee mug in order to succeed in life? Well, photographic printmaking is really no different.

So, over the next several months, very occasionally and in no great hurry, I'm planning to write a few articles about the craft of classic photographic printmaking***. (I can't believe it's already been a whole year since I first started thinking about doing this.) With any luck, I will get my act together sufficiently to make a few videos, although that's asking a lot of my currently nonexistent videomaking skills (anyone want to help?). I hasten to add, to forestall the inevitable jumped-to conclusions, that no, I am not "returning" to film. Unlike some (and no disrespect to them), I don't happen to see film and digital as an either/or proposition. I shoot digital. Just not exclusively. And no, TOP is not becoming a film-only site (I'm sure somebody's going to say that, somewhere). Our coverage by and large will not change.

So—why do this? Well, I'm hoping it will be fun for me, educational for some of you who have grown up with digital, gratifying for those who already love printmaking, and historical for those in the future who might be curious as to the state and changing nature of classic optical-chemical photography in the 'teens.

Mike

* It's pronounced "WALK-uh-shaw," or sometimes something a little closer to WALKIE-shaw." Although it's widely believed locally to mean "Little Foxes"—to the point that there are statues of foxes sprinkled around town (that might also be because of the Fox River, which runs through the middle of town)—it is actually a sort of bastardized or transmogrified version of the name of the leader of the local native tribe when the area was first settled by Europeans.

It's also a very good web name, because there is only one Waukesha in the world. Google it, and you get us.

**Cameramakers control the outflow of NOS by carefully manipulating the price. As the stock dwindles, the price rises, slowing sales. This enables the camera to remain "in production" for longer. This is typically done with higher-end cameras when the manufacturer knows that there is no longer demand sufficient to justify either another run or a replacement model.

***I've encouraged Ctein to write a bit about digital printmaking. He's thinking about it.

Send this post to a friend

Please help support TOP by patronizing our sponsors B&H Photo and Amazon

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2011 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

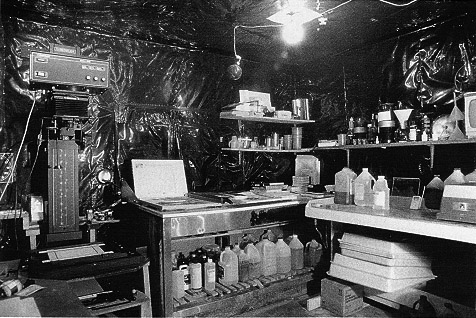

Featured Comment by Carl Weese: "If anything, interest in traditional photographic print making seems to be on the rise. It looks as though we will fill three 'Introduction to Platinum' workshops this year at The Center for Alternative Photography. It's a very craft-oriented weekend course, starting by making ten pictures targeted for platinum printing, developing the film, and then making Pt/Pd prints on hand-coated paper.

"In the past the students have mainly been advanced large format photographers with lots of experience at silver printing. But that's changed. Recently, a lot of the participants have never used a view camera, never developed sheet film (or any film) and never made a silver print, much less a platinum one. It's all new to them, and they seem to love it.

"Practical benefit? Well, a couple participants have been photography teachers who want to be able to teach the medium, a few are professional photographers trying to transition into the Fine Art Market who wonder if Pt/Pd will give them an edge, but most simply have seen and admired platinum prints and want to see if they can manage to do the craft themselves."

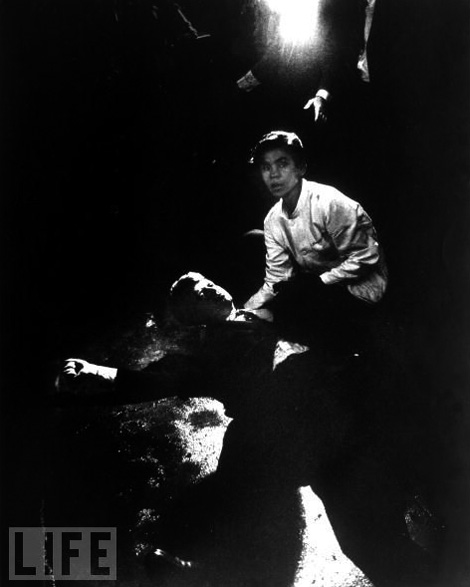

Featured [partial] Comment by Lynn: "I haven't printed in a darkroom for 35 years—and I miss the fun of it, and the excitement of watching an image appear in the developer tray. Watching an inkjet incrementally spit out a print just isn't the same. However, my digital darkroom just astounds me with its capabilities, and the fact I can work in colour—an impossible dream 35 years ago—and that I can produce better quality prints now than I did back then is just wonderful."

Mike replies: I agree. Master printers in the medium are still relatively rare, but the digital medium itself indeed can't be beat for color printing. The only traditional color printing process I truly loved was dye transfer, and both of the best dye transfer printers I knew (Charlie Cramer and Ctein) now print their current work with inkjet printers.

Featured Comment by mark lacey: "I'm so looking forward to this. I teach darkroom work and am constantly amazed how many young people get the craft element and see it as a fun recreational activity, as a polar opposite to sitting in front of a computer all day which so many people do nowadays. I'm probably an extreme example because I'm the only person I know who even loves developing film, I get so excited looking at the negs as they come out of the tank, for me that's the magic moment. It takes all sorts I suppose."

Featured Comment by Steve Jacob: "Oddly enough, although I don't propose to use film again for any reason, I find the comparison quite interesting.

"With film, it was developing that put me off. I was impatient to get to the print stage, so it always seemed like a chore. There was always the risk that you could mess up a whole roll, and I sometimes did. A waste of both film and chemicals.

"Printing on the other hand was actually good fun because it was where you got final control over contrast. It was a creative process, you could see what you were doing and you finally got something to hang on the wall.

"By comparison, digital processing is a breeze, whether from a RAW file or a scanned negative. In this case, all the creative control is exercised during the processing, not the printing, so it is the creative part of the whole process. But the last step, pressing the print button, can be the most frustrating part of it.

"Calibrating and 'dialing in' a new printer and paper combination inevitably turns out to be a process of trial and error, which would be OK were it not for the cost of ink. It would also help if the documentation for most printer drivers was less opaque.

"Of course you can go mail order, but even so I think people who find digital printing a pain are excused. If Ctein can lend us poor suckers a hand (and save us some ink) it would be much appreciated."

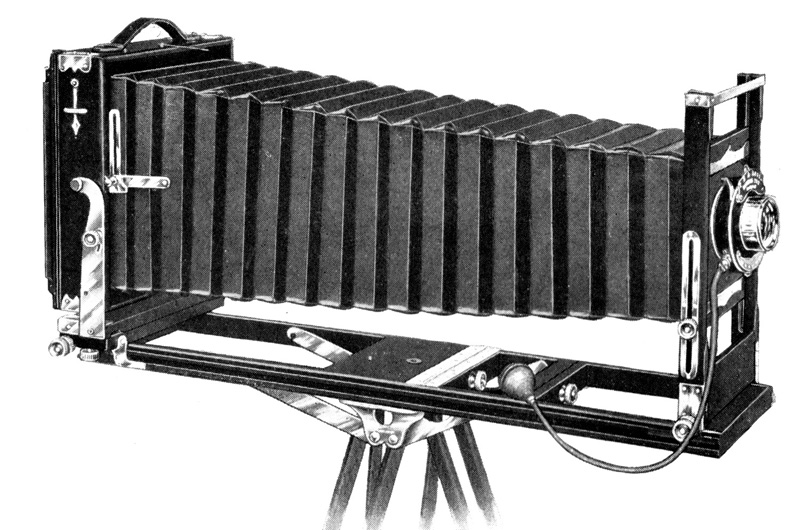

Chamonix whole plate camera of the type owned by both Oren and Mike.

Chamonix whole plate camera of the type owned by both Oren and Mike.

"Maybe that's natural, because the physics and chemistry of photography can be endlessly interesting to people who are so oriented.

"As someone who is 'result' oriented, they often leave me bemused and sometimes astonished. I don't think I've ever been drawn to a photograph because of its sharpness, but other people obviously are—how often (on other forums, like Digital Photography Review or Luminous Landscape) have you seen side-by-side photos of a gorgeous model in a low-cut gown, or no gown at all, but the commentary is on the difference in separation of the eyelashes? Or the fact that Image A has more color artifacts showing around the fourth eyelash from the left, and therefore, that camera simply isn't usable for serious work? Maybe this is why geeks don't get laid...they're counting eyelashes.

"I can think of no famous art photograph—NO FAMOUS ART PHOTOGRAPH—in which ultimate sharpness is critical. Photographs need to be 'sharp enough,' and no more. (I can think of a few in which blur is critical, or at least helpful, like Caponigro's 'Running White Deer.') But you can repeat that endlessly—NO FAMOUS ART PHOTOGRAPH DEPENDS ON ULTIMATE SHARPNESS—and be endlessly ignored.

"It also seems to me that these technically oriented people take technically oriented photographs, most often, landscapes, which function as tests of the things they're interested in—sharpness, resolution, and other qualities that are essentially technical aspects of the camera-lens-sensor unit. You rarely see them writing about composition, values (tonal qualities), color, etc., which are aspects of the brain unit. And they are rarely street shooters, because it's very difficult to get test-like photos in real street shooting. What they really like is to get down in a slot canyon with a heavy tripod and a 60-MP medium format digital back, so that nothing moves, and then see how many striations they can separate out in the sandstone.

"So, it's fairly fruitless to talk about the fact that a small scratch on your lens is essentially meaningless ('The lens is unusable, unusable, I tell you!') or that a few cosmic rays won't make much difference in film. Their goal is perfection in the system, not in the image. They may well realize that can never get there (they're usually pretty smart folks) but that's the goal anyway. They are all about technical issues, and not really about art.

"I often think that they're a little wistful about the fact that they're not artists, so they attempt to reach art through more and more technical perfection. In the meantime, teenagers like the Turnley Bros. are out banging around the neighborhood with whatever camera and lens they can get their hands on...and making art."