It might surprise you to learn that most "big" (little-known) words aren't big. The least-known words (fylfot, gossypol, absquatulate, obloquy) are on average only one letter longer than common words known to most English speakers. Many five-syllable words (university, humiliation, electricity, vocabulary) are well known to most people who are fluent. "Incomprehensibilities" and "uncopyrightable" are long words, but not hard ones. But very few English speakers can define "fetial" on the fly.

Another oddity: writers don't tend to have big vocabularies. They're typically only on the middle to middling-high side. The reason is plain once you know it: if you use words your audience doesn't know, you have failed to communicate. This is especially true when the main word in any given sentence, the one that needs to do the most work, is little-known—which is a pet peeve of mine and something I try to avoid when I play with words. For instance, "The professionals are blessed and cursed with being hierophants of our cult." Hierophants—smarty-pants—huh? The sentence is meaningless unless you happen to know that "hierophant" is a word derived from Greek that means "a person who brings religious congregants into the presence of that which is deemed holy."

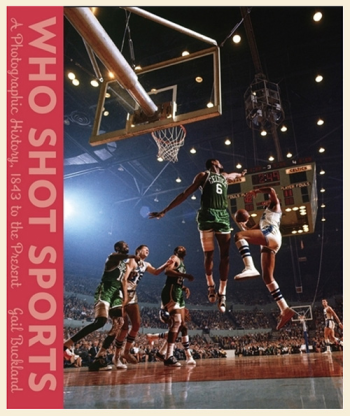

That's a sentence by Peter Schjeldahl, writing in The New Yorker about an important show of sports photography at the Brooklyn [NY, USA] Museum called "Who Shot Sports: A Photographic History, 1843 to the Present," curated by Gail Buckland.

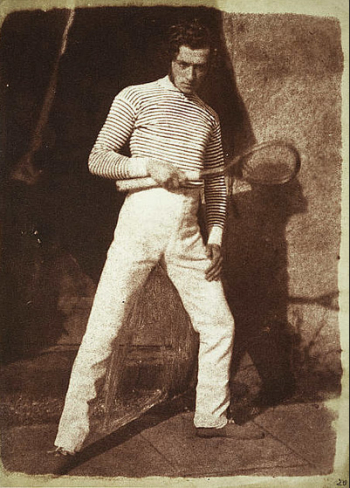

The show begins with the earliest known sports photograph [the article begins]: a calotype, from 1843, by the pioneering Scottish team of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, of a gent who holds a badminton racket across his smartly clad body in an oddly worrying manner, as if it were a weapon. We get that his pastime is glamorously serious and seriously glamorous. (Peter Schjeldahl)

It's the second review at this link; you'll have to scroll down past the first one.

Exceptionally high vocabularies are impediments to communication. Despite having a rather fat vocabulary myself (I test well...a little too well to be a writer, actually), I tripped over the following sentence by Schjeldahl: talking about Neil Leifer's famous photo of Muhammad Ali standing over Sonny Liston, he says, "But it lacks neither that nor the dramatic irony of Liston's collapse: in effect, prostration to a demiurge of history on the turn." Prostration to a demiurge of history on the turn? I read that three times; sort of get it now, although let's just say I hope there's not going to be a test on that.

The New Yorker has a bit of a problem with this. In the same (July 25th) issue, Hua Hsu's article "Pale Fire: Is whiteness a privilege or a plight?" is finely written and subtly argued, but I suspect I know actual college graduates who would give up on its language before reaching the end of its two and a half pages. It begins, according to the standard New Yorker template, with a specific, concrete event firmly planted in place and time, and then (also typically) shifts to more abstract thoughts, the watery course marked by buoys of book citations and other marker events, help doled out to earnest swimmers who need something to hang on to now and then.

Harold Ross, the founding editor of The New Yorker, considered his somewhat unschooled ignorance to be an asset: he was always getting after his writers to say things more clearly, under the premise that if he didn't get it, lots of his readers wouldn't get it either. He understood the peril of big words, in other words. Hua Hsu's graduate-level language might have slid past, but I'm pretty sure those two single sentences I cited of Schjeldahl's wouldn't have survived the Ross Test.

Here's another review of the "Who Shot Sports" show: "Treating Sports Photographers as the Artists They Are."

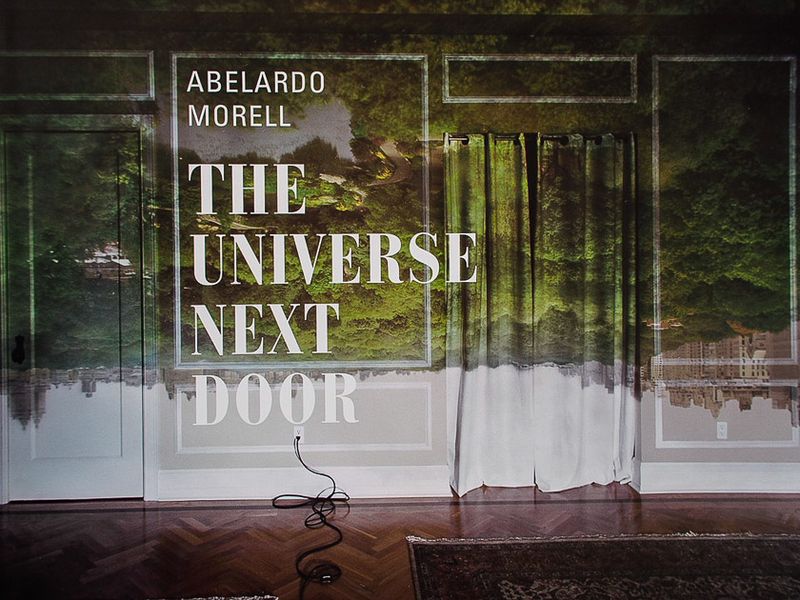

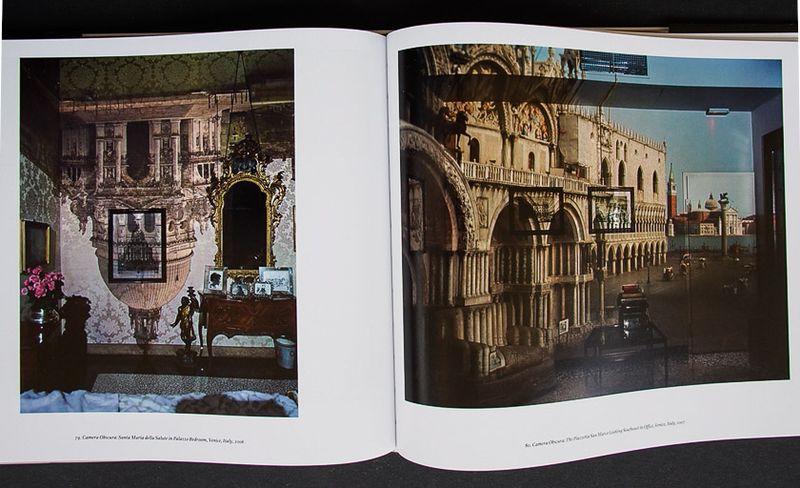

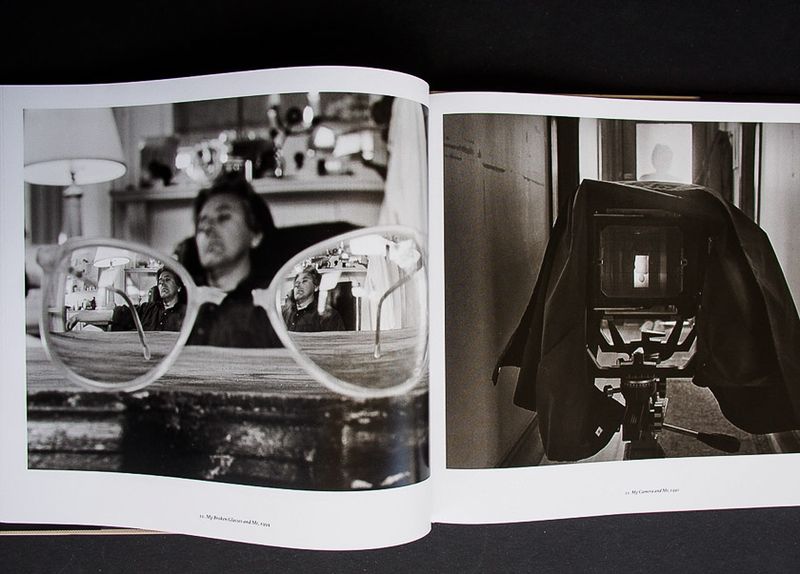

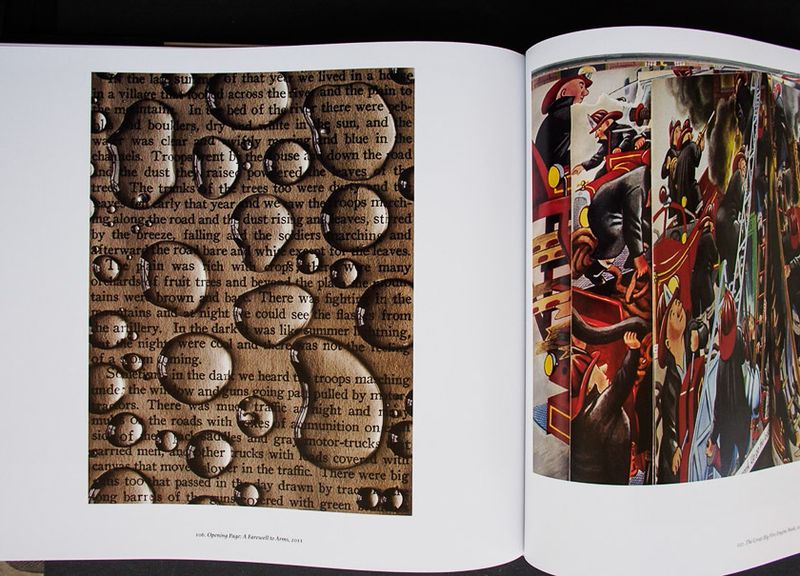

If you can't make the show, there's also a book, featuring nearly 300 outstanding or historically important photographs by 165 photographers. Author/curator Gail Buckland is former curator of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain and former Olympus Visiting Professor of the History of Photography at Cooper Union in New York City. Here's the UK link and here it is at the Book Depository. Sports, as you've got to admit even if you don't like sports, is one of photography's great subjects.

And isn't it cool to know what the first sports photograph was? I didn't know that before today.

Mike

Original contents copyright 2016 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Charlie Ewers: "One of the biggest problems I have teaching university writing courses is convincing some of my students that fancy words and convoluted constructions don't make them sound more important; they just interfere with communication. The best example I can think of—and one that I always use in class—comes from one of my own long-ago high school English courses. After our teacher told us to revise our stories and make them more descriptive, my friend John, writing about a disappointing hike to the top of a mountain, only to find, in his original version, that 'it was so foggy up there that I couldn't see anything at all,' revised his piece to read, 'The evanescent tendrils of moisture obfuscated my optic organs.'"

Tom Burke: "I read this post and then, just for the hell of it, read Lewis Carroll's 'Jabberwocky' (for the first time for several years). Not only did Carroll not care whether people knew his words or not, he made sure they didn't by making some of them up! He obviously did a good job, because several of them (chortle; galumphing; and possible burble as applied to speech) have since made it into the language. In fact, on reading 'Jabberwocky' the meaning is perfectly clear, it's just individual words that are opaque, and somehow they don't obstruct the meaning. An extraordinary achievement."

Mike replies: One of the great things about the whole literary enterprise is that most readers can read at a level well above what they could write. That goes for vocabulary too—I'm convinced I learned the meaning of lots and lots of words just through context...encountering them in texts and getting a sense for what they probably meant given how they were being used. (I still occasionally come across a word I thought I knew from contextual encounters but that I had wrong. "Erstwhile" was the most recent one I remember: I thought it meant "earnest," but it doesn't, it means "in the past"—"erstwhile lovers" are not earnest lovers, but former lovers.)

That we can read above our comprehension level and yet somehow still comprehend is one of the felicitous features of written language.

Jim Richardson: "Besides being so very thankful that sports photography has hereby gotten the artistic honor it so richly deserves, it's just so good to see so many names of hard-working photographers included, most of whom simply labored to do a good job so that their images might effortlessly convey a moment of truth. Not quite so with the quote from Schjeldahl who seems to labor mightily (but fruitlessly) to say what is meant. We might start with the simple difference that every writer should know: the difference between lie and lay. Prostration is when someone lies down in front of a superior power. Sonny Liston did not willingly lie down. He was laid low."

Christopher Mark Perez: "Perhaps it comes from years of reading philosophy, technical and scientific papers, but I find The New Yorker to be a great read. I enjoyed the two articles Mike mentioned. I wish I could write like that."

Mike replies: I find it a great read too—I often find the articles too short—although I find the writing increasingly formulaic under Remnick. The occasional article by a stylist makes the contrast more clear and points out that most of the writers no longer display much individual style.