By Ctein

A couple of comments on my last two columns provide the starting point for this column. John Camp commented that he expects that "printer setup and color management will be much more standardized" within a few years and software will allow one to print well with little experience. Cameron makes a closely related comment on my last column, where he describes the business of going from camera file to a printer-ready file as "photo post-processing" rather than printing.

Both of these comments view printing as the merely physical act of driving a file from bits on a hard drive to ink on paper. But, as Cameron intuits at the end of his comment, "Or am I somehow missing the point of what it is that a master printer does?"

Well, yes, he is. What Cameron calls postprocessing is properly part of the whole custom printing process. There've been several occasions when the client has provided me with a "finished" file to print and I've looked at it and really wished they had sent me the RAW file instead and let me do the conversion and adjustments, because honestly they didn't do a very good job. Please understand that I'm not talking about reinterpreting their vision. I'm saying that anything they could do I could do better. My output file would have had less highlight and shadow clipping (when that's aesthetically appropriate), better sharpness, less grain/noise, and more clarity than theirs. For a start.

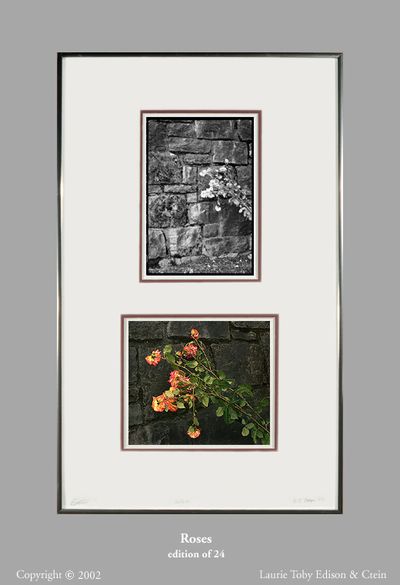

A photograph by Roger Pellegrini before and after custom printing. A lot of what I did isn't going to be very visible in this small, low quality reproduction, but there are eight substantial and important-to-the-final-print alterations. Only three of them were requested by Roger, and only one of them is blatantly obvious. As for the other five, Roger just told me to print as best as I could.

There's a lot I can do with a photograph even if what I'm receiving is the "finished" file. In fact, it's extremely rare for me to print someone's file exactly as they send it to me. Even if they think they're done with it, I can convince them they're not. They may have done 75% of the work needed to make a really great print, but there's another 25% that I know how to do and they don't.

People like to talk about the RAW conversion process as being a lot like developing film, but there are some very important differences. For one thing, film developing is a pretty straightforward and non-aesthetic operation. Unless you're heavily into Zone System antics. Even if you are into such games, film development is about giving you the starting point for a really good print, not about getting you a negative that yields the perfect and ideal print with no further attention. That's what custom printing is about.

RAW conversion lets you make a whole bunch of artistic and aesthetic decisions that film development never does. If you're not superb at that, your final print will suffer for it. If it really helps you to think of RAW conversion as being like development, then you'll be better served thinking of a RAW converter as though it were 10 film developers rolled into one, with all possible combinations of development times, agitations, and temperatures being available. Looked at in that fashion, I can tell you that most people doing RAW conversions are "misdeveloping their film" to a greater or lesser extent.

Another important change is that unlike true film developing, RAW conversion can be done over and over again. The camera file is "fixed;" the conversion isn't. It may be subject to reconsideration and reevaluation as one's aesthetic demands become clearer. That more properly places it in the artistic domain of "printing" than "developing."

Some people think that all they need to get a great print is a well-done RAW conversion. That's true only a small percentage of the time. For example, easily 3/4ths of the photographs I see, film or digital, would benefit from some dodging and/or burning in before they're printed. How many folks do that when they're RAW-converting? Yeah, damned few.

As for John's push-button printing, I think we are already there for 90+ percent of the serious printers (I mean people, in this case). Just pull the printer (now I mean the machine) out of the box, follow the roadmap to set it up, use the canned profiles that your operating system will automatically invoke, and you'll get very good-looking prints. The hassles are the exceptions rather than the rule. I don't think we have to wait for the future for printing to become easy. At least, not so long as it's not extreme, high-end, custom printing.

On the other hand...

I'm genuinely not sure how much printing will be done in the future. Some folks, two weeks back, expressed the interesting notion that it didn't matter if one did one's own printing or not, so long as the photographer did get good prints. I think that's only true if prints truly matter. Many will argue that, especially today, viewing a photograph on a screen simply cannot do it justice, so people are aesthetically shortchanging themselves. I can't support that. After all, traditional slide photographers rarely felt that way, and their best work speaks for itself. Yes, this is relevant.

Some of you old-time slide photographers are going to hate to hear this, but most of your viewing environments were crap. The average slide presentation, even in camera clubs and other "serious" settings, suffered from objectively poor brightness range, sharpness, and shadow detail, as well as distortion and artifacts of many sorts. If you threw quite a bit of money at the problem and were very careful in designing your viewing environment, you'd get something that was, by objective measure, about as good as carefully-made-but-not-exceptional print. You had to burn lots of C-notes to achieve superior viewing. Sorry to be the bearer of bad tidings, but that was true, so help me Kodak.

Meanwhile, the Loyal Opposition is thinking, "Hey, Ctein acknowledged that on-screen viewing can't stand up to a well-made print; hasn't he just refuted his point?" No, to the contrary. Note my repeated use of the word "objective." Subjectively, those projected slides look great! Why? That's very complicated to explain; oversimplified, if you present the brain with a visual experience while isolating it from the surrounding world, your perception expands or contracts to match the experience. The slide, even if shoddily projected, becomes a universe unto itself, not answerable to external objective measurement.

Screen images in any technology benefit from this perceptual illusion. TV, by which I mean the 525-interlaced line, analog-broadcast-bandwidth limited stuff, should look lousy by all objective measure. Instead it looks great all out of proportion to the specs. Ditto with small, limited-gamut JPEGs viewed on mediocre monitors. They look a lot better than they really are. If you throw the kind of money at digital display that you'd throw at a decent slide projection setup, you get a great viewing experience, no matter that some of the technical specs may be mediocre compared to a print.

Personal experience trumps specs every time, and all that really matters in photography is the viewing experience you have when you see a photograph, not one little bit the measurements you can make on a lab bench. We make photographs for people, not photometers.

(Hmm, I like that. You may quote me. Attribution always appreciated.)

Some people gravitate to sheets of paper (I'm one), some to screens. A few are equally happy with either. If what the photographer truly loves and desires (not the same thing) is the image on the screen, whether projected, pixelated, or both, then a print is irrelevant. It can express nothing that matters to them about the worth of their photograph. It's the wrong medium sending the wrong message, just as much as a 50KB JPEG doesn't convey nor inform the viewer very much about one of my dye transfer prints.

There are going to be exceptions. Even a studio-quality 30" display will not do justice to a 4x5 chrome (or digital equivalent). But, neither did traditional slide projection. I'd be surprised to learn that there were ever more than ten people in the entire United States at any given time who had projection setups that could do full justice to 4x5 photographs. What matters is not the specs, what matters is how good it looks and how strongly it can speak to you. Don't underestimate the strength of the projected photograph. A strong print draws your attention away from the rest of the room. A strong screen image owns that room.

That's it for my much-extended musings on printing. Next time, we get back to tech-speak, and a très-cool trick I came up with for using my Olympus Pen at ISO 6400 and liking it!

Ctein's regular weekly column appears every Thursday morning.

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2010 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.