By Ctein

Over the past several weeks, many readers have raised concerns about the permanence of photographs, whether film or digital. Truly, they have every reason to be concerned. It's a problem that has bothered me ever since Henry Wilhelm opened my eyes to this in the mid-1970s (we have been lifelong friends, since).

In practice, photography has not proven to be a very durable set of media. The examples people trot forth of photographs that have survived a century are almost never in their original condition; they are merely recognizable images. Worse, that enduring photographic record of the 20th century, while a far more extensive documenting of humanity than has ever existed before, is but a small fraction of all the photographs made and now lost.

We have the mistaken impression that photography is durable because what has endured is so extensive and we remember victories, not losses. Almost axiomatically, there is little way to remember the losses. It's a kind of cultural posttraumatic amnesia; the photographs that disappear from view mostly get forgotten.

This, of course, is what concerns us all. Photographs are our memories! Unfortunately, we are badly brain-damaged, and while we may be dimly aware of it there is very little we can do about it.

Oh sure, almost all those old photographs (if they physically exist, and most of them don't) can be restored. That is, in part, my business. It's expensive. For what I charge to restore a mere dozen or so individual photographs, you could have all the data recovered from the most decrepit and ancient hard drive. That's an important point: theory says you can preserve old photographs against deterioration and restore them when they do deteriorate. Theory also says you can recover digital data from almost any medium at any time. All it requires is a sufficient application of expertise and money. Especially money.

Nice theory. In practice, how often does that happen? Very rarely. The theoretical permanence of well-processed black-and-white photographs and prints or of well-processed Kodachrome film is as irrelevant to the collective discussion as assuming that everyone will follow proper archiving practices, backups, and storage-medium/format updates for their digital photographs. Those media don't constitute the vast majority of photographs and most of the photographs made in those theoretically-durable media were not well-stored and preserved. If your stuff still looks good, I am happy for you; just realize that you are one of the lucky few.

In the real world, no modern photographic medium, analog or digital, has shown itself to be durable. It only lasts when ordinary people take measures that are, well, extraordinary.

I have been pondering whether the situation is now better or worse than it used to be, and I don't have a clear-cut answer. Mostly that is from a lack of historical perspective; we are simply too newly into the digital age to know what the future will bring.

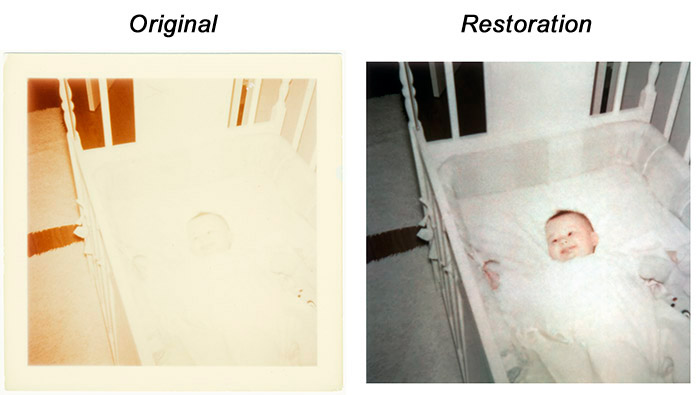

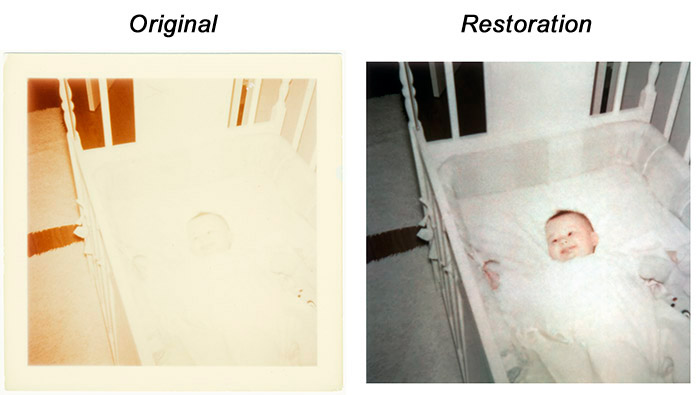

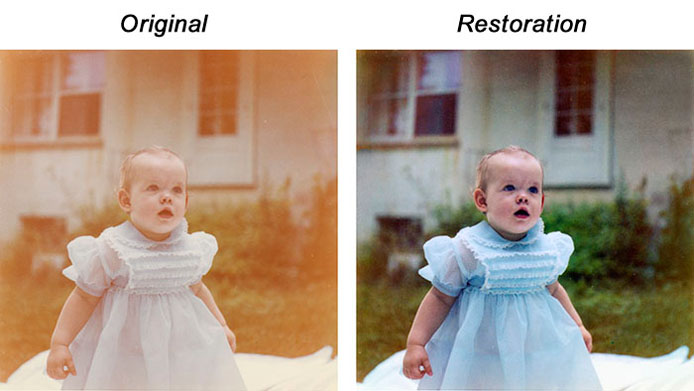

1. On the left, an all-too-typical color photograph from 1950. It's essentially blank to the naked eye. As the right figure shows, it's possible to recover the image to a satisfactory degree, but hundreds of dollars of work went into achieving this. What percentage of old photos will ever get this treatment?

In the case of film photography, the record is all too clear. Most photographs, slides, negatives, and prints, from 1946 through 1960 are already deteriorated to the point where they are essentially unviewable (illustration 1). Most of them are recoverable but never will be recovered. Not enough money, not enough time, not enough skilled restorers on the planet.

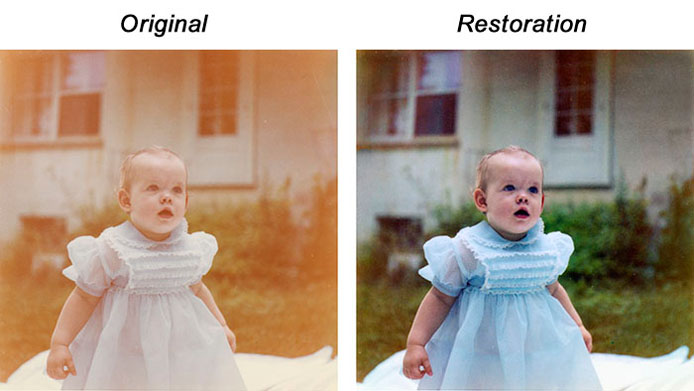

2. By the early-mid '60s, prints were a lot more durable than in the '50s, but that's damning with faint praise. This degree of restoration only costs in the double-digits, but that's still more than most photos will ever receive.

The photographs from 1960 to about 1980 are on the same path (illustration 2). On average they are in better shape because materials improved and less time has passed. On average they are in worse shape because of the increasing shift to chromogenic materials which, back then, lacked in permanance (although God knows they were much better than their 1950s predecessors). Give it another 20 years and most of that cultural record will be gone. I'm not talking about the really important events that were documented up one side and down the other; I'm talking about the mass cultural record that those of us alive at the time made for our own pleasure and to preserve our own memories.

A third of a century of photography is already mostly lost. Very little of it will survive intact another 25 years.

Things got a lot better starting in the early 1980s. E6, C41, late EP2, and RA4 film and paper processes all led to increasingly permanent materials. By the end of the Film Era, chromogenic prints had better display permanence than even dye transfer as well as an entirely acceptable dark-keeping lifetime. Late-generation E6 slides are, in practice, as permanent or more so than K12 Kodachromes were. These photographs will continue to deteriorate, but nowhere as rapidly.

Even black-and-white, on average, has become more permanent, primarily because the vast majority of earlier stuff was really badly processed. I get to see the evidence for that regularly; it is not a pretty sight. Black-and-white RC papers, for example, may not be as durable as fiber-based papers when given ideal processing, but I assure you that a far smaller fraction of fiber-based prints ever received anything close to ideal processing. That theory-vs.-practice thing again.

That is an extremely abbreviated history of analog photographic permanance. So abbreviated, in fact, that it includes numerous minor inaccuracies. The overall picture, though, reads truly enough; view it in broad strokes.

So what about digital photography? The initial period is going to be rocky. Hell, it already has been rocky. I'm going to guess that the majority of photographs from the first decade of the Digital Era will be lost (for some definition of "first decade:" your dating system may differ from mine). Again, I'm talking real practice, not theory. With digital, it's even more about practices than inherent characteristics of the media. Said practices were very, very sloppy.

I suspect that is changing rapidly. Your average camera-wielders are getting much better about preserving their photographs, much more quickly than I expected. The reason, I think, is because the everyday records and data of one's life are going increasingly electronic.

My housemate, Paula, and I were surprised this last year when the IRS told us they would no longer be sending us paper tax forms to fill out; we would have to download them from online. Hardly a burden; we still file on paper, so that's what we did. What really startled us was to learn how much of a minority we are in; only about 5% of all tax returns are filed on paper these days. We had no idea.

That's the way the average citizen's world is very rapidly moving, and in that world there are strong forces at work to improve overall digital durability in practice as well as theory. In the dark, on the hard drive, all bits look the same. Doesn't matter if it's someone's photographs, their music, video, or movie collection, their electronic books, their bank statements and check stubs, or their tax returns. As a pleasant, inevitable side effect one's personal photographs will get preserved and maintained along with all the rest of one's electronic life.

Analog photography lost more than a third of the century. I'll be very surprised if digital photography loses even a quarter. Maybe not even much more than another few years beyond the already-past decade.

I hate it when any photographs are lost. But I've come to sincerely believe that we are better off now than we used to be in the Analog Era. I've seen how badly that worked out.

Ctein

Ctein, the author of Digital Restoration from Start to Finish, writes a regular weekly column (not always on restoration issues—sometimes, it's parrots) for The Online Photographer that is published on Wednesdays.

Send this post to a friend

Please help support TOP by patronizing our sponsors B&H Photo and Amazon

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2011 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

Featured Comment by Jim: "It always comes down to money! But, why should we preserve them? I read recently that there are 43 billion photos now uploaded to Facebook, another five billion to flickr. And, I would guess, perhaps trillions living on hard drives around the world. I'm not convinced it's a good thing they survive.

"I burned tens of thousands of negatives and prints from 50 years of my photography (I'm a photojournalist) heavily documenting my area a few years ago because I couldn't give them away to historical societies, etc. Sent out dozens of letters, made numerous phone calls. Too expensive and space-intensive to store and conserve them, they all said. Too expensive to scan and convert them all to digital, they all said.

"For most of my photography career I worried about archiving prints and negatives, and then digital files. But I don't concern myself with it anymore. Most of these trillions of images being constantly recorded these days will never be looked at again anyway.

"Perhaps they should be as impermanent as our own memories, which gracefully degrade as we age and then disappear when we die."

Mike replies: That's a painful story, Jim. I almost hate to say this, but it's at least possible that you destroyed your work during its stay in the "Trough of No Value." That doesn't mean it might not have been valuable to future generations or historians, just that it wasn't valuable to them yet.