Going cold turkey on optical finders: My experiences with EVFs

By Kirk Tuck

(Please understand that this post is meant to be somewhat tongue-in-cheek. Few new tech innovations are without their faults, just as many mature viewing implementations have on their side decades and decades of familiarity.)

You can look high and low in my studio these days but the only optical finders you'll uncover are those in old film cameras or the ones in digital cameras now considered too eccentric to be sold (the Kodak SLR/n and the Kodak DCS 760C). All of my current digital cameras feature electronic viewfinders. I am now working without a safety net. Really.

It all started with that Olympus EP2 and its little friend, the VF-2 finder. A gorgeously designed camera and one that works well within its file size limitations. And a finder that set the standard for resolution and clarity upon its introduction.

But after working with several generations of mirrorless cameras such as the Olympus E-P3, both the Panasonic GH2 and G3, and most recently the Sony a77 and a57, I became completely addicted to the lure of the mini-TV screen in the eyepieces of my cameras. Here is my list of reasons why:

- Pre-Chimping(tm). Post-shot chimping, as it is done with current, EVF-deprived cameras, is an iterative process. You can really only compose with an OVF (optical viewfinder)—you can’t see any of the other parameters that the camera will impose on your final image until you actually take the image and then review it on the back screen of your camera. How primitive! So you shoot a test frame and then you evaluate it. Then you change a few things and you shoot again to test. It's a process that, in the hands of a rank amateur, can last a long time. Pre-chimping (tm) with an EVF means that the second you bring the camera to your waiting eye you'll see the composition of your intended image and the way the white balance will handle the scene as well as any sort of digital adaptations you've made to your in-camera shooting parameters such as contrast, saturation, sharpness, or art filters. You can correct as you watch and then shoot. No post chimping required. Once you've pre-chimped(tm) I'm not sure you'll ever want to go back.

- Have you heard about focus peaking? It's not available in your OVF. You'll need to upgrade if you want this feature. Lots of people like to use older, manual focus lenses on their brand new digital cameras and all too likely they end their experiments in sadness and misery because the focusing screens in the OVFs destined for digital work aren't at all optimized for manual focusing. And all of us over forty years of age seem to have a hell of a time achieving critical focus on our older technology cameras unless we put the camera on a tripod and engage (semi) Live View. At that point we can fine focus our fine old glass using a small portion of the image. It's not so much fun, especially if you are in an area with lots of bright light around you, bouncing off the LCD screen on the back of your camera. If you have a camera with an EVF that includes focus peaking, you'll have a nearly foolproof focusing method that works by showing you color outlines of the things you've gotten in sharp focus. With EVF cameras you can use this method while shooting stills or while shooting videos. You can do it handheld, in bright light and without cropping down to 10% of your image. Very nice.

- How about a super quick check on an image just to make sure your subject didn't blink during your exposure? Sure, with old tech you could take the camera away from your eye, find the review button, shield the screen on the back from glancing and image degrading ambient illumination and then review, or—you could take advantage of new tech by setting a short duration image review that works in your finder while it's still at your eye. Most of the new cameras will show you a preview and you can go back to a live image with a soft touch on the shutter button. How nice. And if you need to review a shot while on the deck of a boat in tropical sunlight or in a giant field of white sand you'll be able to do it with no more effort than bringing the finder up to your eye and looking. Pity the poor OVF owner, chained to their massive Zacuto and Hoodman chimney finders, awkwardly holding their cameras up with one hand while trying to keep their finder-assisting-extra-accessory from sliding around with the other hand....

There are just a few niggling issues that still need to be perfected for EVFs; but we can't be more than half a generation away. At least when we consider the EVFs in the Sony NEX-7 and the Sony Alpha a77 and a65 cameras as current benchmarks. But I would be remiss not to mention them.

- Since the camera is continuously taking a sensor image and running it through the processing pipeline before feeding it into the eyepiece monitor there is a statistically relevant time lag. You'll need to learn how to "lead" a fast moving subject. It takes practice but it is do-able. I've practiced on my kid when he runs competitively. I'm not perfect at tracking him yet but I wasn't perfect with an OVF-hampered camera either.

- Since you are getting a video feed you'll have to change the way you shoot with flash. With an OVF you get the same light level through the finder with any exposure setting. If you set a high flash sync it doesn’t affect the image in the finder. With an EVF enable camera if you set a high shutter speed and medium aperture in a room with low light (as you might when working with a studio flash) you'll no longer be able to see a bright (or any) finder image with the setting most people use for the EVF, which shows what a scene will look like using the inputs and exposure controls you have set. You'll need to set the camera to "gain up" the finder image so you can see your subject and work with them. The darker the environment the more noise in the finder image you'll get. If you work a lot with flash inside you'll want to test out an EVF camera before you trade your hard won Imperial Credits for one.

- The EVF shows you the approximate gamut of the color space you have set in the camera. This is good because you see how stuff might render in print or on the screen of your computer at home. This is now known as real time visualization (a nod to Ansel Adams's pre-visualization practice). This should be considered a positive, but most people look in the finder and see an image that looks "too contrasty" with blocked up shadows. There are one or two workarounds, depending on how you shoot and what kinds of files you like. If you're a died-in-the-wool Raw file shooter you can go into your parameters and set the contrast on your default JPEG style/setting to a lower value (less contrast). This will add detail to your shadows and highlights. If you are a JPEG shooter you can always set your color space to AdobeRGB instead of sRGB but it won't buy you quite as much correction. There are also brightness control settings for the EVFs and you might want to experiment with them as well. I'm sure we'll have a wider gamut on future screens, but as I stated before, it is an effective pre-visualization for many styles of shooting. But high contrast lighting is the EVF's Achilles heel.

After assessing the pros and cons of the different finders and weighting in my own quirks and my seeming need for novelty on a regular basis, I dumped an enviable accumulation of Canon EOS cameras, lens and flashes and bought into the Sony SLT camera system. I was drawn in by the EVF (really) and the stationary mirror (kinda) and not in the least by the fast 12fps shutter. I've used the Sony a77's now for the better part of a month and recently added their newest camera, the Sony a57. I also bought a mix of both super G lenses and cheap lenses. The two I love the most are the ultra cheap 30mm ƒ/2.8 DT Macro and the 85mm ƒ/2.8 SAM lens. They feel cheap in your hands but the quality of the imaging is superior. (All the pictures in this post were taken with the Sony a57 and the little 85mm lens.)

So, how have I fared in the post optical imaging universe? I am serious about this: When I shoot with continuous lights (like my favorite LEDs) or by modified window light, I am very, very happy. I can control my shoots while rarely taking my eye off the finder. I was shooting food for a new Austin restaurant, handheld, last Saturday, and getting a level of fluidity in my shooting that I've never experienced before. I could look at the food and turn a knob to adjust exposure while I watched the effect in psuedo real time. It's a great way to shoot food.

I'm now so used to the pre-chimping method I described above that I rarely find myself lowering the camera anymore to post-chimp. (The rear screen seems to exist now as a conduit for showing my results to my clients.) While not necessarily directly related to the EVF, I have found that with the stationary mirror and the electronic first shutter curtain, coupled with in body stabilization, I am able to perform magic tricks with blur-free slow shutter speeds. The different systems all work together to yield a final result that seems very, very sharp.

I have been shooting video for years now and I can't tell you how much more efficient a camera becomes if it can do full time phase detection autofocus while shooting video. And being able to see it in a light-protected finder is such an operational plus. When you add in focus peaking, you are getting close to the wish list for many videographers. (The only two video features I want to see in the next Sony camera are manual level controls for the audio in video and a headphone jack, à la Nikon and Canon's latest cameras.)

The one place where I know the EVF is less effective than OVF is in the use of studio flash. If you are working with powerful modeling lights it won't bother you as much, but if you are working with little 60-watt peanut modeling lights stuck in big lighting modifiers, you won't be as happy with the speckles and pixie dust that dances across the screen while you view.

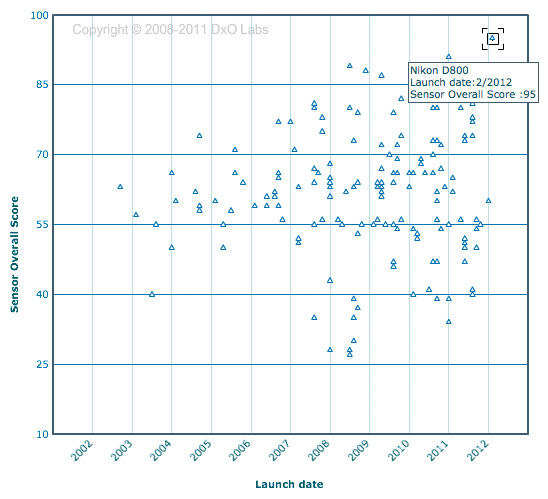

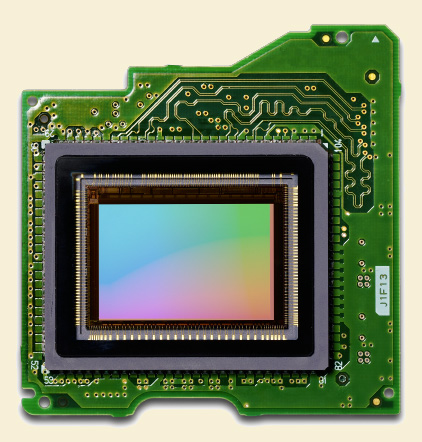

I'm not suggesting that anyone abandon a system and an approach to still photography that they love and are wedded to, but the EVF is something that I think will filter down into most cameras because, as the price of sensors continues to fall, the single most expensive part of every SLR camera out will be the semi-silvered glass pentaprism and mirror assembly. As consumers demand more for less, and as OLED screens become more ubiquitous and hence less expensive, it doesn't take a telescope to see big changes coming in viewfinders.

EVFs and LEDs are a great combination. Add in a great, low noise sensor and you're in the sweet spot. I always hear that "it's not the arrow, it's the Indian." I think we're switching from the long bow to the cross bow, though. The endless march of progress.

Kirk

Kirk Tuck is a monthly contributor to the Online Photographer. He is the author of five books on photography and lighting including his most recent, LED Lighting: Professional Techniques for Digital Photographers

. He makes his living photographing for corporations and advertising agencies in and around Austin, Texas. He is also a masters swimmer and spends far too much time in the pool.

Send this post to a friend

Please help support TOP by patronizing our sponsors B&H Photo and Amazon

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

Original contents copyright 2012 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved.

Featured Comment by Don: "Kirk, the English longbow was a vastly superior weapon to the crossbow. It's why the French were defeated at Agincourt. The English (and Welsh) archers whipped off the strings and stuck them under their caps when it rained. The French archer's crossbow strings got wet and stopped working. Crossbows take time to reload—in that time an English longbow will have fired multiple arrows. On Sundays every Englishman was required to practise archery with a longbow after church. The French so feared our bowmen they used to cut off their fingers when caught so they could no longer draw a bow. Hence the origin of the two-fingered salute—given by English archers to the French to let them know what was about to come down on their heads.

"The English/Welsh archers using the longbow completely outclassed the French with their crossbows."

Featured Comment by John Ashbourne: "Don's featured comment only refers to part of the reason for the outcome at Agincourt. Another major reason was the French emphasis on dated technology—elaborate and cumbersome armoured cavalry which bogged down in the clinging mud due to exceptionally heavy rain. there is an obvious parallel here—of which I am uncomfortably aware when I take out my 1Ds3 and 70-200mm rather than the X-Pro1—but then had circumstances been different at Agincourt the heavy cavalry would have come into their own just as in some circumstances there is nothing so good as the 'mighty Canon.'"

Featured Comment by Roger Bradbury: "The idea with the longbow was to get as many arrows into the air as possible; you are bound to hit something. Are you sure you weren't interested in the Sony's 12 fps Kirk?"

Mike replies: First of all, the topic was viewfinders yet here we find ourselves arguing about weapons technology at Agincourt—yet another demonstration of why I love this blog.

Just wanted to point out in relation to Roger's comment that in my recent book rec Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, author S.C. Gwynne goes into considerable detail about weapons technology on the Southern Plains and how it affected the struggles between the main players. He points out that until the advent of the six-shooter—the main purpose of which was to be used on horseback, not in duels as in the movies—Comanches' bows and arrows were actually superior as weapons to the slow muzzle-loading rifles originally used by the Mexicans and the Texans, and gave them an advantage.

The various analogies to cameras seem perilous to me, albeit admittedly tempting.

Featured Comment by Rodolfo Canet: "Given the path the discussion has taken, never has the tag 'shooting techniques' been more appropriate!