["Open Mike" is the anything-goes, often off-topic Editorial Page of TOP. It appears on Wednesdays. Sorry this took so long to complete! While writing it I went down rabbit-holes as never before. Kind of amazed I made it back. —Ed.]

-

Apropos the recent "Overtourism" post, here are some smashingly good books that will allow you to go on great adventures without leaving the warmth of your own cozy hearth:

Joe Simpson, Touching the Void (2004). In some ways I'm sorry this was made into a movie, because it will spoil for innumerable souls the great pleasure of reading the book with no idea of the outcome. Read that way, it was one of the best "thrillers" I've ever come across in either fiction or nonfiction. If ever the existential trap of being in a body on Earth was boiled down to a purer essence than that faced by the protagonist at the suspended peak of the action in this book, I can't conceive of it—it has the heightened symbolic perfection of an invented fairy tale. The friend must make his Hobson's choice; the fallen man faces his terrifying dilemma. I've never felt the predicament of another human being more vividly from mere words on paper. Unless you've had the story spoiled for you by the film, set aside some time for this short little thriller. It's terrific.

Joe Simpson, Touching the Void (2004). In some ways I'm sorry this was made into a movie, because it will spoil for innumerable souls the great pleasure of reading the book with no idea of the outcome. Read that way, it was one of the best "thrillers" I've ever come across in either fiction or nonfiction. If ever the existential trap of being in a body on Earth was boiled down to a purer essence than that faced by the protagonist at the suspended peak of the action in this book, I can't conceive of it—it has the heightened symbolic perfection of an invented fairy tale. The friend must make his Hobson's choice; the fallen man faces his terrifying dilemma. I've never felt the predicament of another human being more vividly from mere words on paper. Unless you've had the story spoiled for you by the film, set aside some time for this short little thriller. It's terrific.

Gary Kinder, Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea: The History and Discovery of the World's Richest Shipwreck (1998). If you have a technical and logical cast of mind and love gear and science—and nonfiction—forget chests of pirate gold buried on the beaches of remote Caribbean islands; here's the story for you. When the S.S. Central America, a side-wheel steamer returning from the California gold fields laden with humans and tons of gold, went down in a maelstrom in 1875, it came to rest under miles of water, location unknown, where it was long believed to be unrecoverable. That was until a brilliant and determined inventor-explorer set his sights on the impossible. The real story is better than any romantic assumptions about "lucky finds." The book, which took Kinder nearly ten years to write, was a bestseller when it came out in 1998.

...And it's told from the perspective of no later than 1998. From there, the story went on. Remember the Coke bottle in The Gods Must Be Crazy? The S.S. Central America treasure has since triggered that sort of trouble and skullduggery—the treasure-hunter absconded with the dough and became a fugitive. And I have to say, when I read Ship of Gold, I wondered about what was to come. What has happened since 1998 probably deserves another book, probably written by someone else. Still, the story this book tells is a great one. Gary Kinder, who lives in Seattle, now teaches writing seminars to lawyers across the U.S.

Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff. Contrary to the impression imparted by the news, recent research suggests that the world is getting progressively less violent—and part of the reason might be that people have been reading novels for the last several hundred years. Novels allow us to climb inside other peoples' heads and sympathize with their experience, which, the theory goes, affects our thinking by increasing our sympathy and compassion for those outside our own type and our own tribe. Though not novels, armchair adventure books can be counted as a way to go places you'll never go and understand the world in ways you never could from firsthand experience.

This is the one book on this list I haven't read. But how can a list touting books about going on great adventures from "the warmth of your own cozy hearth" not include "the final frontier"—what used to be called "outer space"? 'Twould seem like an omission. Even if you're an inveterate traveler, you'll never go where the people in this book have gone.

You'll have to tell me whether you think Tom Wolfe's celebrated book deserves to be on this list. I've been meaning to read it for years, but in the queue of all the books I have a-waiting it never quite seems to make it all the way to the top.

Cheryl Strayed, Wild (2013). Some writers have the knack of getting you to read fast and effortlessly, like water flows downhill. This book "reads itself," as the saying goes. Here's the blurb, because I can't describe it better: "At twenty-two, Cheryl Strayed thought she had lost everything. In the wake of her mother’s death, her family scattered and her own marriage was soon destroyed. Four years later, with nothing more to lose, she made the most impulsive decision of her life. With no experience or training, driven only by blind will, she would hike more than a thousand miles of the Pacific Crest Trail from the Mojave Desert through California and Oregon to Washington State—and she would do it alone. Told with suspense and style, sparkling with warmth and humor, Wild powerfully captures the terrors and pleasures of one young woman forging ahead against all odds on a journey that maddened, strengthened, and ultimately healed her." Read the sample; a luminous book. Suspend critical judgement and go get into Cheryl Strayed's head for a while. You won't regret going along on the trip.

Cheryl Strayed, Wild (2013). Some writers have the knack of getting you to read fast and effortlessly, like water flows downhill. This book "reads itself," as the saying goes. Here's the blurb, because I can't describe it better: "At twenty-two, Cheryl Strayed thought she had lost everything. In the wake of her mother’s death, her family scattered and her own marriage was soon destroyed. Four years later, with nothing more to lose, she made the most impulsive decision of her life. With no experience or training, driven only by blind will, she would hike more than a thousand miles of the Pacific Crest Trail from the Mojave Desert through California and Oregon to Washington State—and she would do it alone. Told with suspense and style, sparkling with warmth and humor, Wild powerfully captures the terrors and pleasures of one young woman forging ahead against all odds on a journey that maddened, strengthened, and ultimately healed her." Read the sample; a luminous book. Suspend critical judgement and go get into Cheryl Strayed's head for a while. You won't regret going along on the trip.

Mark Twain, the first quarter of Roughing It (1872), the part about the stagecoach journey, and the first section of Life on the Mississippi (1883) in which he recounts his early training as a steamboat pilot. There are a lot of things we no longer know about Twain now, now that he's no longer put forward as the Great American Novelist, one of which is that, despite earning several fortunes, he never escaped money worries. It kept him scribbling away at a manic pace, ever the entertainer, always on the hustle. Consequently there's a junky, kitchen-sink quality to some of his books, both early and late, where he seems to lose his way or try too hard or where he gets too wrapped up in his own schtick. I wasn't nearly as charmed by the later sections of Roughing It, which get, well, rough—they lose the quality of first-rate travel writing which the stagecoach section has in abundance—and although some people like the later sections of Life on the Mississippi, the part written about his later-life journey from St. Louis to New Orleans seems perilously close to padding to me, and doesn't have nearly the interest of his memories of his early days on the river, when life was new and the riverboat was king. Despite these irregularities, Twain at his best is so good that the good bits are worth winnowing out from the fluff and junk and the parts done for money.

Mark Twain, the first quarter of Roughing It (1872), the part about the stagecoach journey, and the first section of Life on the Mississippi (1883) in which he recounts his early training as a steamboat pilot. There are a lot of things we no longer know about Twain now, now that he's no longer put forward as the Great American Novelist, one of which is that, despite earning several fortunes, he never escaped money worries. It kept him scribbling away at a manic pace, ever the entertainer, always on the hustle. Consequently there's a junky, kitchen-sink quality to some of his books, both early and late, where he seems to lose his way or try too hard or where he gets too wrapped up in his own schtick. I wasn't nearly as charmed by the later sections of Roughing It, which get, well, rough—they lose the quality of first-rate travel writing which the stagecoach section has in abundance—and although some people like the later sections of Life on the Mississippi, the part written about his later-life journey from St. Louis to New Orleans seems perilously close to padding to me, and doesn't have nearly the interest of his memories of his early days on the river, when life was new and the riverboat was king. Despite these irregularities, Twain at his best is so good that the good bits are worth winnowing out from the fluff and junk and the parts done for money.

Ernesto Che Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries. Based literally on diary entries, and published in 2003. There are three books I'd recommend to motorcycling existentialists: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Oliver Sachs' autobiography On the Move (there's very little in that book about motorcycles, but what there is sticks in my mind), and this. It's a slight book (175 pages), obviously not by a professional writer, and not the most famous or best "on the road" book. That would have to be, well, On the Road. But there's something immediate and authentic about Che Guevara's little memoir that both makes his outsized legend human-sized again and that speaks immediately to the impulsive urge to travel and experience the world that is so characteristic of wild youth. You can skip this if you've grayed or have anything reflexive against Cuban revolutionaries. If you're young, check it out. The book is alive in a way that some better books aren't.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways (1982). I bought this book because I wandered into a bookstore on Dupont Circle in DC to look at records. A crowd had gathered. They were listening raptly to a small, soft-spoken man with old-fashioned country-style clothing and wire-rimmed eyeglasses with thick lenses. His name was Bill. As I recall, his wife had left him, and he had lost his job as a teacher, so, with time on his hands and little left to lose, he set aside his European last name, Trogdon, and started using his father's Osage Indian name, Heat-Moon. He, as his father's youngest, was called Least. He constructed a small living enclosure on the back of his old pickup truck [Note: see correction in the Featured Comments] and set out to find something to write a book about. His idea was to stay off the superhighways and stick to the secondary roads, typically colored blue in the old Rand-McNally Road Atlases—and try to find what was left of the old United States. That was in 1978. He traveled 13 thousand miles in three months, and the book spent 42 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and has never been out of print.

I got to talk to him for a quarter of an hour, and he inscribed and signed the copy of the first edition I bought for the purpose—alas, long lost now. It wasn't in good condition anyway, because I read it twice and loaned it out to a number of friends too. Maybe one of them has it still. This book will be better for older, knowledgeable folks who find contemplation agreeable.

Jon Krakauer, Into the Wild (1996). I identified with this one because the doomed protagonist, Chris McCandless, was more or less of my generation and his father Walt worked with my dad at NASA. It's a strange and terrible story that, despite the author's attempt to provide answers, leaves many questions unanswered. Former Outside magazine writer turned best-selling book author Jon Krakauer uses the tale in part to explore what drives young men to climb mountains and seek adventure; as a set-piece, the pages about the author's harrowing quest to sit astride the summit of the Devil's Thumb, and how it did or did not change his life (I'm not about to give that away), is worth the price of the book in my opinion. There are ancillary materials available now, including a video by his siblings attesting to their bad home life growing up.

Krakauer's most famous book, of course, is Into Thin Air, his controversial but compelling first-person account of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster. As popular as it was, that book ends in desolation and left me with a bad feeling in my soul that lingered for a month. (On the other hand, it is surely the seminal literary work of the age of overtourism—we've all seen the bizarre spectacles that have taken place at Everest since then.)

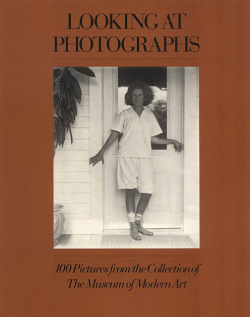

Eric Newby, What the Traveler Saw (1989). There's a uniform edition available from HarperCollins UK of all of Eric Newby's books (here's the UK link to the author page), and I can see why—he's an affable tourguide and excellent company. It's very tempting to collect all of these. I haven't regretted any of the time I've spent with him. But while few of these titles have any direct connection to photography, I'm going to choose What the Traveler Saw because it is overtly a recollection of Newby's travel photography. Many of the pictures in the book were taken with a plain-Jane Pentax and a 50mm lens, but I enjoyed the pictures that go along with the writing a lot—Newby is one of my favorite non-photographer photographers. You can find the hardcover used, which would be the way to go with this one.

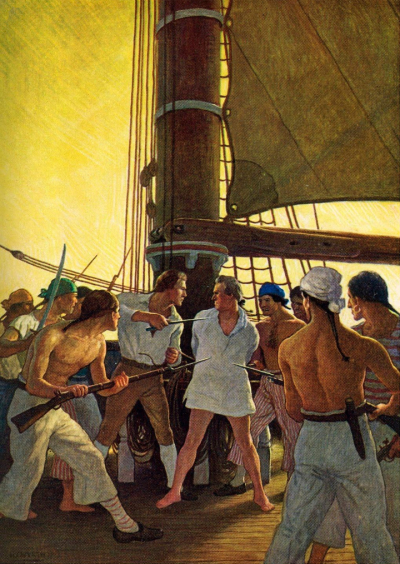

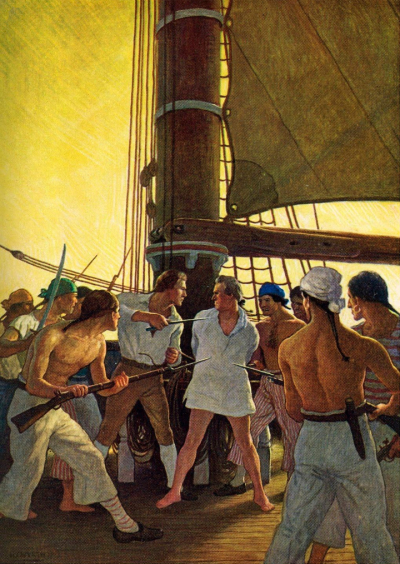

N.C. Wyeth illustration from Mutiny on the Bounty

N.C. Wyeth illustration from Mutiny on the Bounty

Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, The Bounty Trilogy. For a seagoing adventure I might have chosen the newer In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex by Nathaniel Philbrick, which won the 2001 National Book Award and was made into a movie by director Ron Howard in 2015. That one is the real-life story that caused a public sensation when it happened and inspired Herman Melville to write Moby-Dick. Philbrick's book is a modern retelling of the true story of the whaling ship Essex, which was rammed, stoved-in and sunk by an enraged sperm whale, and the subsequent fate of the crew in the whaleboats (used as lifeboats), who ended up so much in extremis that no fewer than seven crew members were cannibalized by their shipmates. Two of the survivors wrote first-person accounts; one went mad.

But when I ask myself which I would rather have read if I could read only one of the two, it's no contest: the greater sea story (possible the greatest, unless you count The Odyssey of Homer, available in a new translation), and one of history's great tales, is the classic Bounty Trilogy from the nineteen-thirties. The Trilogy, first issued as such in 1936, comprises the original three books in one volume: Mutiny on the Bounty (1932), about the voyage of the HMS Bounty and the daring mutiny; Men Against the Sea (1933), the tale of Bligh's epic and unlikely return to England; and Pitcairn's Island (1934), the story of the mutineers seeking escape from the wrath of the Crown. (Descendants of the Bounty mutineers still populate Pitcairn.) It is beautifully written, fascinating in terms of human nature, a multifaceted story, and gripping reading.

There are a number of editions. Maybe you can land one with N.C. Wyeth's illustrations. There's a serviceable book club edition published by Grossett & Dunlap. You might poke around in eBay Books or Abebooks and see what you can find. Note that books titled "Mutiny on the Bounty" might just contain the first book rather than all three.

There have been three movie versions. The original in 1935 featured Charles Laughton's famous turn as Captain Bligh (worth seeing) and Clark Gable as Fletcher Christian. A remake in 1962 stars Trevor Howard as Bligh and Marlon Brando, then perhaps the most famous movie star in the world, as Christian. Here, the backstory is more interesting than the film—it was the start of Brando's reputation for being difficult, and kicked off what the actor later called "my f--k you years." (A Saturday Evening Post article about the production was titled "Six million dollars down the drain: the mutiny of Marlon Brando.") Not counting a made-for-TV version, the final attempt came in 1984 and was called simply The Bounty. A title as self-contained and iconic as "Mutiny on the Bounty" needs to be shortened? But that was the fashion with movie titles in the '80s, and this was possibly that fashion's dumbest result—ridiculed at the time as sounding like a roll of paper towels. It's like making a movie version of The Grapes of Wrath and calling it "The Grapes." Anyway, that one, my least favorite of the three, featured Anthony Hopkins and Mel Gibson (whom I've personally never cared for as a human) in the lead roles.

The movies are all enjoyable but all flawed in one way or another. As with Jane Eyre, a definitive movie version remains to be made. The books are better.

Old, but still not to be missed. The Bounty Trilogy has fired the imaginations of generations of readers.

Mike

Original contents copyright 2019 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

Please help support The Online Photographer through Patreon

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

[Note: In deciding which comment to "feature" I wanted to include a few reader recommendations, but I can't include them all. Please don't assume that I think the recommendations I "featured" are any better or worse than other recommendations in the regular Comments Section. Not the case. —MJ]

Featured Comments from:

Burt Porter: "My top choice is Alf Lansing's account of the Shackleton expedition, Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage. It was published in 1959 and is still in print. A very readable account of one of the great adventures. And since this is a photo blog, after all, check out the glass plate prints from the expedition. They are glorious."

Mike replies: The photographer was Frank Hurley, whose accomplishments were extraordinary.

Marco: "On the same thread of Into The Wild and mentioned in this book, I liked also Finding Everett Ruess: The Life and Unsolved Disappearance of a Legendary Wilderness Explorer, by David Roberts. A painter, not a photographer, but he met Dorothea Lange and had a portrait made by her."

Steve Rosenblum: "I think Krakauer is a very talented author. However, Into The Wild just made me angry. I don't think there is anything particularly romantic about throwing your life away due to stupidity. I have spent a lot of time in wild places. You must enter them well prepared and respectful of the power and unpredictability of nature. The protagonist seemed like an earnest enough young man, but hiking into the Alaskan wilderness unprepared with only a bag of rice and no real survival skills is just suicidal. Perhaps that was his intent, but to me it just looks like a wasted life."

Mark Roberts: "Man, I'd have been upset if you'd left out Eric Newby. ;-) My favourite of his is A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush (which has what may be the best, non-cliché travel book ending ever) but The Last Grain Race is pretty good, too."

Michael Bade: "If you like Newby, you might try The Last Grain Race. He shipped out on a square-rigged four-masted ship for the Australia run. He also took his father's Contax and photographed the voyage—the version I have included the photos he took during the voyage. His writing puts you in the scene and then the photos complete what's in the mind's eye—recommended!"

Mike replies: I don't know which editions of The Last Grain Race are illustrated and which aren't. Some of those photographs are included in What the Traveler Saw. The most complete collection is in a book called Windjammer: Pictures of Life Before the Mast in the Last Grain Race.

Clay Olmstead: "Excellent list! Here are three more, in no particular order: The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon by David Grann is a trip into the Amazon before it was being incinerated (and another good book made into a mediocre movie); Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe by Laurence Bergreen gives a compelling account of the risks and rewards of exploration in the 16th century; In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette by Hampton Sides tells the story of exploration for purely scientific purposes, when there was a common belief in a warm ocean at the North Pole (completely without any scientific data to back it up, much like global warming deniers today)."

Mark Sampson: "Eastern Approaches, by Fitzroy Maclean. A young British diplomat, he traveled throughout Central Asia in the 1930s, when it was closed to foreigners by the Soviet regime; and that's only the first part of an engaging, very well-written book. Some people have suggested that he was a model for Ian Fleming's James Bond—certainly it's plausible. The book is not well known in the USA, but it should be."

Popum: "Bravo, Nordhoff & Hall. I first read the trilogy 60+ years ago as a young teen...stuck with me like few books have. When I was being interviewed to become a Trustee of our local library, I was asked what book was my all-time favorite. You can guess the answer. It was a great conversation starter since no one on the interview committee had even heard of it. By the way, the librarian was not on the committee. P.S. Thanks to Nordhoff & Hall I ended up becoming the President of the Board of trustees."

Moose: "William Least Heat-Moon outfitted his (Ford Econoline) van with a bunk, a camping stove, a portable toilet.... It was John Steinbeck who used a custom made camper on the back of a truck for his travel across the US, as told in Travels with Charley. I reread it fairly recently, and must say that Blue Highways is much the better book. For Eric Newby, I also recommend Around the World in 80 Years. I find it difficult to imagine a better start to the introduction to an autobiography than 'To have reached the age of eighty years more or less unscathed is by no means une affaire mince, an insignificant matter, which is how a French friend of more or less the same age described it. How I contrived to reach sixty and then seventy without noticing it is still a mystery to me.' Copiously illustrated with photographs."

david stone: "Have you been stalking me? Most of those are on my favorite books list. I guess we're on the same page, so to speak."

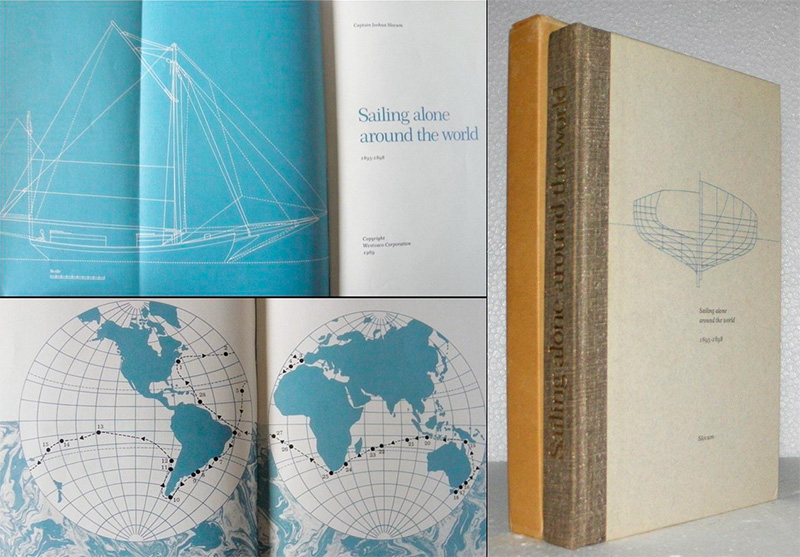

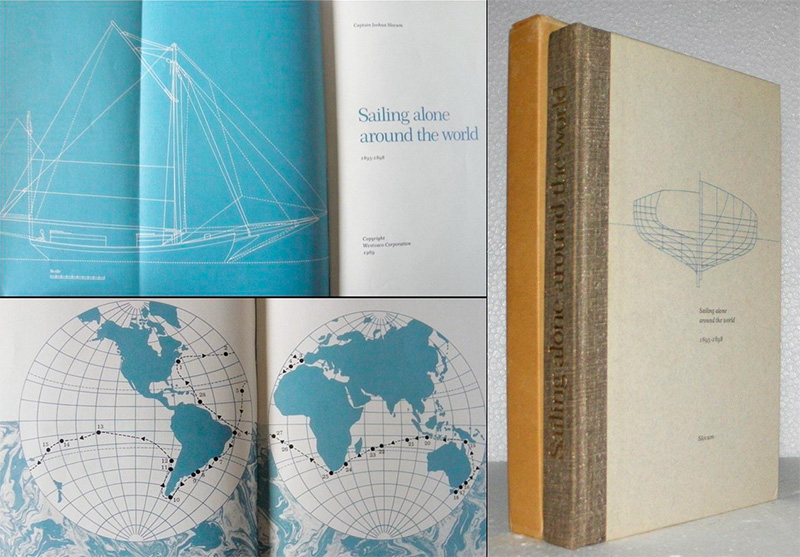

Bill Tyler: "In the late 1800s, an old sea captain, Joshua Slocum, rebuilt a small wooden vessel from the keel up, and then sailed it solo around the world. His account of the voyage makes any modern sailing adventure seem tame by comparison. There were no radios to call for help, no GPS for navigation. He did not have funds for a chronometer, the necessary instrument for determining longitude. It’s an amazing story of seamanship and adventure, very readable, and full of the flavor of the times. I recommend it highly. Sailing Alone Around The World, by Joshua Slocum."

Mike adds: That book is out of copyright protection and in the public domain, so there are numerous cheap paperbacks. That means you have to be a little careful about what you're buying. For example, the end-of-chapter Summary in a so-called "Annotated" edition starts out like this: "Some people get bore while reading the novel . But when you started to fell the novel, you cant miss a single line from the novel." (All [sic].) This one looks well made, although I can't vouch for it. There's a large print version from Dover reprints. People who are proud of their bookshelves might want to seek one of the nice hardcover editions: the most famous is The Century Company's edition from around the turn of the 20th century; there's a trim and spruce little hardcover from Konëmann, and Shambhala even got into the act in the early 2000s. The nicest in my opinion is a fine press edition by Westvaco from 1969, which is beautifully designed and illustrated if you like that sort of bookmaking. Westvaco (West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company) was a paper manufacturer that subsidized an original fine press edition of a classic every Christmas for a number of years. That's the edition I have. It's rare but not particularly expensive.

The Westvaco edition. Illustration from Amazon.

As with other old titles that have enjoyed sustained interest over many years, it can be fun to haunt Abebooks, eBay's Antiquarian & Collectible Books section, and used bookstores to see if you can find something interesting or unusual.

Gijs: "Thanks for the list of exciting books. I can also recommend two history books which are almost entirely adventure: The Arctic Grail and Klondike: the Last Gold Rush, both by Pierre Berton. There are events or experiences in both books which make John Krakauer's Into Thin Air read like a Sunday stroll in a park with a playground!"

Iain: "I recommend books by Wilfred Thesiger: 'I had come here in search of adventure: the mapping, the collecting of animals and birds were all incidental. The knowledge that somewhere in this neighbourhood three previous expeditions had been exterminated, that we were far beyond any hope of assistance, that even our whereabouts were unknown, I found wholly satisfying.' from The Life of My Choice.

"His photographic archive of 38,000 images is held at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England, and is available online."

John Denniston: "If you enjoyed The Bounty Trilogy you would like Caroline Alexander’s update The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty. Alexander researched admiralty records, contemporary newspaper and magazine accounts, plus private letters from the families of the mutineers, and found that not only was Bligh was one of the more benign naval commanders of the era but that the Christian and Heywood families did a public relations hatchet job on him to protect their upper class family reputations. Bligh, who was not from the upper class, had no friends in high places."

Mike replies: I own and have read the Caroline Alexander book. I generally like to "read around" books I'm reading—that is, read secondary books that augment or complement the main course. It's often wise to get two sides to every story. I also have a strange habit of pairing books: picking two books that are better read together than reading each alone. That's probably just an eccentricity.

Mark Sampson: "Okay, one more worthwhile obscurity, Horace Brock's Flying the Oceans. Brock was a navigator and later a pilot for Pan American Airways in the 1930s and '40s, the era of the flying-boat Clippers. They were the Space Shuttles of their time. Talking about navigating over the Pacific in 1937, he said 'the navigation math was not so difficult; it was just that you could never make a mistake.' Fascinating, and, naturally, long out of print."

Mike replies: The one to seek out there is the Stinehour Press edition from 1979.

raul v.: "Patrick Leigh Fermor's A Time of Gifts is the epitome of travel literature for me. A war hero and prolific adventurer, Paddy was greater than life and his literary talent shines in his books where he describes a world long gone—the Europe between the World Wars."

Mike replies: I've never read him (or heard of him prior to this, to be honest) but that must be a famous one. There's a Folio Society deluxe slipcased edition and it was reprinted in the NYRB Classics series.

Mani Sitaraman: "That's a excellent list of travel books, Mike, but the capsule synopses by you are even better! I'm pleased to say I've read most of them, but will seek out the ones I haven't.

"Back in the 1980s, there was a resurgence in interest in travel books, perhaps sparked by the literary historian, Paul Fussell and his book, Abroad: British Literary Travelling Between the Wars which is a must read. His book also sparked an interest in Robert Byron's book The Road to Oxiana about a 1930s car trip from Europe to Central Asia. I can recommend that, too. Lastly, although he is terribly out of fashion, my favorite travel book, albeit fictional, is by Rudyard Kipling. It's Kim, and the description of the Grand Trunk Road in Northern India rang very true to me, even a hundred years later, and corresponded with my own memories of road travel in Northern India in the early 1960s, when I was very young.

"P.S.: You should do more non-photography book recommendations and reviews here at TOP, from time to time, Mike. I really enjoyed your post."