Reviewed by Geoffrey Wittig

W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. $63 (U.S.)

W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. $63 (U.S.)

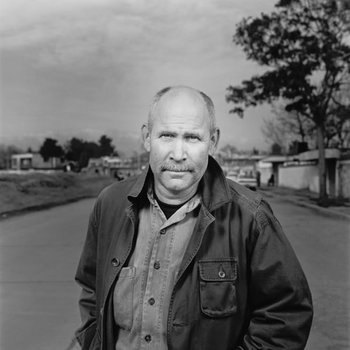

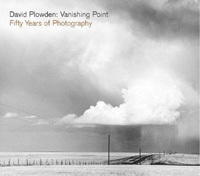

David Plowden may be the best photographer you never heard of. He began his career as an assistant to O.Winston Link in 1958, briefly studied with Minor White and Nathan Lyon, mentored with Walker Evans, and subsequently followed his own path from 1962–2005. His work is exclusively black & white, and might be described as lyrical documentary. The sheer depth and volume of his output is remarkable, including more than 20 books. Plowden has focused on locomotives, steamboats, bridges, factories, barns, small towns and rural remnants. This may strike some readers as dull fare; no lofty mountains, no celebrities, no mayhem or nudity. But for folks of (ahem) a certain age—say, over 50—this body of work is an intricately detailed portrait of the world we grew up in. For you youngsters, this was the world your parents and grandparents knew; back when America (rather than China) was manufacturer to the world. Plowden's work has a great deal in common with the best FSA photography; but he kept at it for nearly fifty years.

Vanishing Point is David Plowden’s recently published retrospective. This is an imposing book; at 352 pages, it's almost too big to read without setting it on a table. As an example of the printing arts, it is simply beautiful. The duotone photo reproductions are excellent, with deep blacks, subtle tonality and well-preserved shadow detail. Only the finest varnished tri-tone stochastic printing (barely) exceeds this level of quality. The accompanying text is clean and readable, elegantly set in a modern digital typeface. This is a pleasant surprise, and addresses one of my pet peeves. Digital typesetting has freed book designers from the constraints of hot metal and photo typesetting. Perversely, most modern books use these digital methods to (badly) imitate low-end offset printing circa 1972. Expensive art books are sadly not immune to this repellent practice. Vanishing Point’s typesetting by contrast is superb, right down to the ligatures and text (lining) numerals missing from ordinary books. A subtle point, but obvious to the discerning eye. The list price of $100 may seem steep, but discounts are the rule, and it surely provides more value than three of the overpriced softcovers crowding the shelves at Borders or B&N.

The book’s introduction is a detailed chronology of Plowden’s life, describing how a youthful obsession with steam locomotives and trains sparked his artistic career. His work gradually took the form of an extended lament as the last steam engines disappeared, followed inexorably by the Great Lakes steamboats, steel plants, and prairie farms he subsequently photographed. Plowden’s final project was A Handful of Dust, published in 2006. In it his austere prose and photographs documented the silent demise of once thriving farm towns he had visited decades earlier. In the summer of 2005 he quit photographing for good, despairing at the disappearance of his subject matter.

The photographs in Vanishing Point are grouped by subject matter and theme, beginning with steam locomotives in the late 1950’s, progressing through Lake steamers and tugboats, steel mills and bridges, to prairie farms and small towns. The 280 duotones include his iconic "greatest hits" such as "Phoebe Snow, Scranton, PA" (right) and "Statue of Liberty from New Jersey," with many less well-known gems. Plowden’s photos are meticulously crafted; he spent two years at an Indiana steel plant puzzling out how to preserve detail in both shadows and incandescent molten iron. His compositions are conventional, but carefully judged. Many of his early railroad photos include men; as his work matures you see fewer people, but a sense of honest blue-collar work and human craft is pervasive. In his late work, abandoned grain elevators and empty storefronts attest to a way of life that is dead and gone. Viewed sequentially, the images illustrate the apogee and long decline of America’s industrial and agricultural heartland. Plowden's real concern is the human touch; how honest workmanship and ambition transformed heartland America into something approaching art. And how that art has turned to dust after decades of neglect.

The photographs in Vanishing Point are grouped by subject matter and theme, beginning with steam locomotives in the late 1950’s, progressing through Lake steamers and tugboats, steel mills and bridges, to prairie farms and small towns. The 280 duotones include his iconic "greatest hits" such as "Phoebe Snow, Scranton, PA" (right) and "Statue of Liberty from New Jersey," with many less well-known gems. Plowden’s photos are meticulously crafted; he spent two years at an Indiana steel plant puzzling out how to preserve detail in both shadows and incandescent molten iron. His compositions are conventional, but carefully judged. Many of his early railroad photos include men; as his work matures you see fewer people, but a sense of honest blue-collar work and human craft is pervasive. In his late work, abandoned grain elevators and empty storefronts attest to a way of life that is dead and gone. Viewed sequentially, the images illustrate the apogee and long decline of America’s industrial and agricultural heartland. Plowden's real concern is the human touch; how honest workmanship and ambition transformed heartland America into something approaching art. And how that art has turned to dust after decades of neglect.

In a postscript Plowden describes his equipment, technique, film & paper choices in detail. He has always done his own darkroom printing. His expressed goal has been to portray his subject as directly as possible, without craft calling undue attention to itself. This self-effacing, modest approach is exactly appropriate to the subject. It's also the diametric opposite of the monumental, "look at me" style employed by artists like Edward Burtynsky or Andreas Gursky.

David Plowden by Hank Koshollek

I think the character of David Plowden’s work could be summarized as Walker Evans without the condescension. If you love Robert Frank, you’ll probably find Plowden too gentle and sympathetic. Not enough irony. If Gursky’s your thing, you may even find Plowden boring. But if you’ve ever looked in regret at a shuttered train station, or if you regard Wal-Mart as the Anti-Christ, you should have a look. This beautiful volume is the definitive summation of a worthy career. It may inspire you to check out Plowden’s earlier books—more than twenty in all, four of them still in print.

______________________

Geoff Wittig is a small town family physician with a passionate photography obsession. He spends most of his free days hiking and photographing—mostly rural landscapes—and sells enough prints to pay for ink and paper.

Featured Comment by Arthur Gross: "There's also a retrospective show going on now at Catherine Edelman gallery in Chicago to celebrate his 75th birthday and the release of the book. Plowden is a wonderful printer, and quite a number of images from the book are in the show as well. Highly recommended for Plowden fans or fans of B&W photography in general."