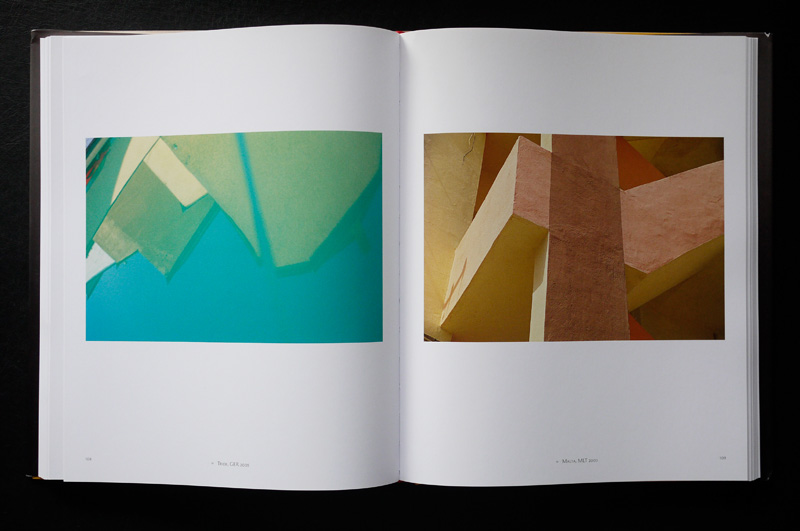

[Editor's note: I haven't been able to procure usable JPEGs of sample pictures from Photography Unplugged to use with this article. To give you an idea what the pictures in the book look like, there is a small selection of nine examples on the main page at www.harald-mante.de.]

By Jim Hughes

A while back, Mike asked people to talk about their favorite lenses. I was

busy on a project at the time, so stayed silent. But I did think about it.

And in the middle of the night I came up with an answer that surprised even

me: over the course of many decades of photographing—generally carrying a

camera wherever I go, not because I need to make a living or burnish a reputation but because I

still love what it feels like to take pictures—my favorite lens turns out

not to be a lens at all. The "optic" I feel most comfortable seeing my world

through is actually a film. Kodachrome, to be precise.

Okay, if pressed, I could name a glass lens or three. At the top of my list

would be the 50mm ƒ/2 Schneider Xenon fixed to my eminently pocketable

Retina IIa folder. This 60-year old lens is really sharp yet still manages

to render Kodachrome’s abundant tonalities with a soft brush. Then there’s

my reliable "modern" antique, the minuscule 35mm ƒ/2 Canon that I regularly

mount on my indestructible Canon 7s rangefinder (both circa 1968). Shooting

color—all I do now—the Canon produces rich and deep transparencies that

somehow possess the enduring look of old-time black and white. In fact, most

of my compact Canon RF lenses perform similarly. Must have been a design

philosophy back then. Many of today's lenses seem oddly cold and calculating

by comparison.

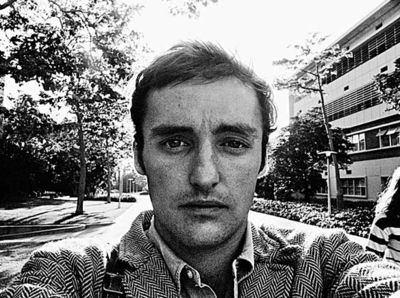

Jim Hughes with his Retina IIa. Note the Leitz 1:1 bright frame finder.

Blackberry photo by Peter Smith.

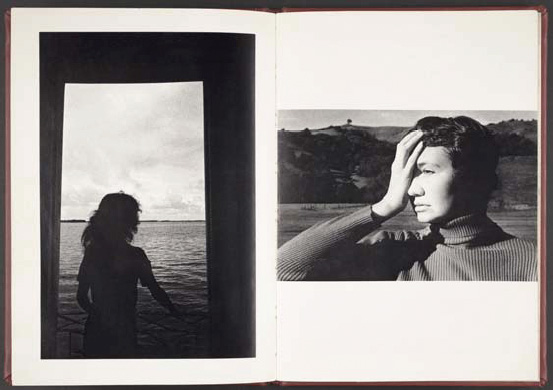

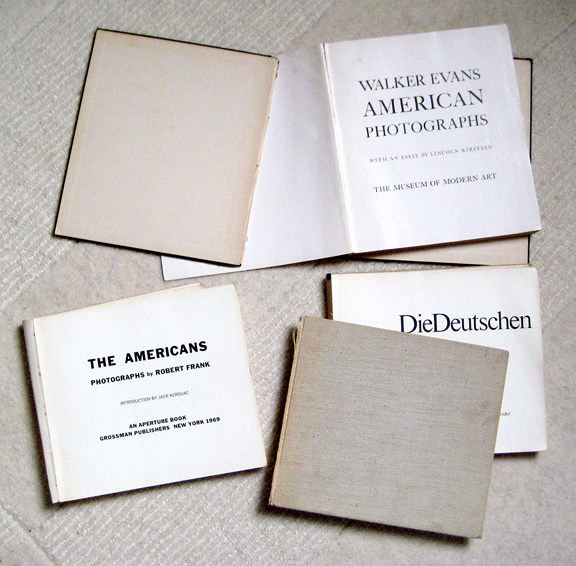

Brings to mind Ralph Gibson's comments the other day regarding books (which

I agree with, no surprise). I've known Ralph since he arrived in my office

at Camera 35 with a box full of prints under his arm and a plan to

self-publish them in a book. He wanted a portfolio in the magazine to help

make it happen, and I was more than happy to oblige (as I was later, with

Larry Clark's Tulsa, at Ralph's suggestion). Ralph is, by the way, one of

the smartest, most articulate photographers I've had the pleasure to work

with. Even then, he thought of the photo book as a distinct art form; books

offered the ability to pair images on facing pages, he said, expanding and

deepening their meaning, which can't be done as effectively in exhibits (or

today, on the web). "A less ephemeral experience," I think his words were

regarding photographs in books.

I also agree with Ralph's comparison of digital versus film. When I did the

Ernst Haas in Black and White book, the publisher, Bulfinch, wanted the

reproductions be be made from digital tri-tone scans, the newest and "best"

process in 1992 (these days, we would be talking Quad-tones, or maybe

Octo-tones!). I wanted the reproductions to be made in old fashioned

offset-lithography duo-tone, with the plates made from film produced

optically in one of those giant room-sized repro cameras on tracks. I

thought the look of the latter would be a better match for Ernst's B&W

photographs, most of which were made in the '40s, '50s and '60s with Rolleis

and Leicas. So the publisher—reluctantly and at no little expense—did a

test, running both the old and new technologies on a sampling of prints.

When we spread out the press proofs for comparison, the decision was clear:

the digital scans seemed to cause ink to float more on the surface of the

paper; done that way, Ernst’s images had less depth and were overly-sharp

at the edges of things, imparting a harsh tonality he never envisioned. I

wanted the ink to be absorbed by the paper more. The differences were

subtle, but real. Low-tech won, expensive and labor-intensive though the

production may have been. (Of course, this may go a long way toward

explaining why the book has never been reissued, turning it into a

hard-to-find collector’s item.)

Given digital's relatively rapid ascendancy, it can come as no surprise that

today, virtually all books—pictures, words, whatever—are made using new

technologies whose rough edges presumably have been mostly smoothed out

since 1992. Scanning and the ability to create digital files can rightly be

thought of as having brought about the democratization of publishing, a good

thing if ever there was one.

And as Ralph noted in his email to TOP, "the book will surely prevail."

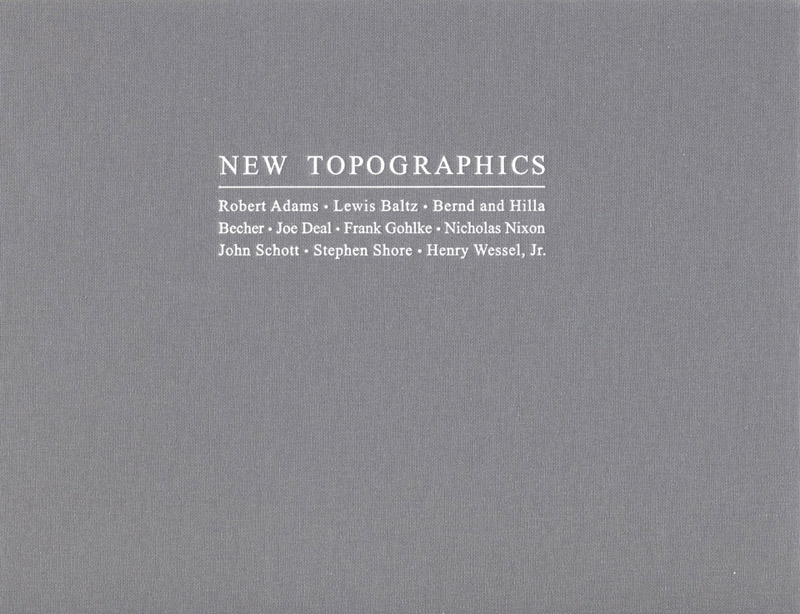

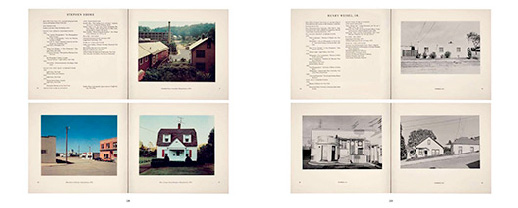

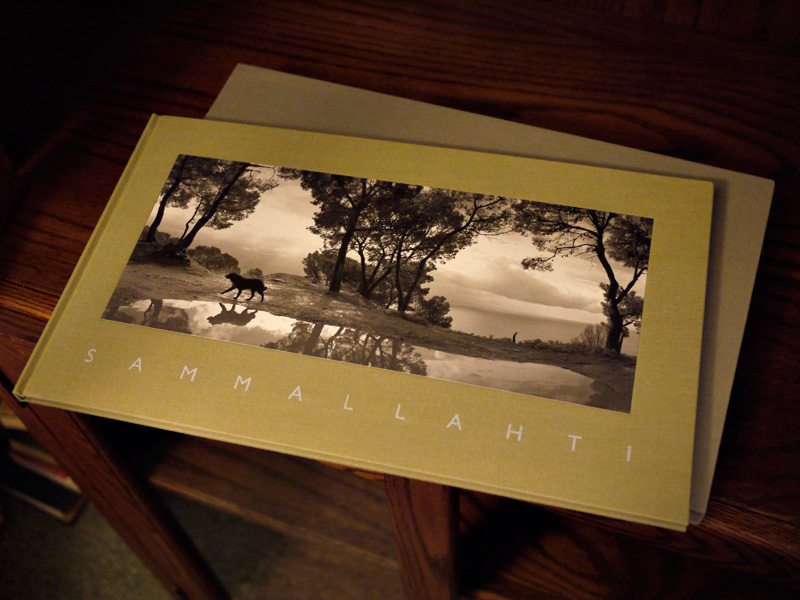

Consider the volume currently in my hands. Photography Unplugged

And as Ralph noted in his email to TOP, "the book will surely prevail."

Consider the volume currently in my hands. Photography Unplugged (2009:

Rocky Nook, Santa Barbara, CA—here's the U.K. link

(2009:

Rocky Nook, Santa Barbara, CA—here's the U.K. link ), is its title—not a

little ironic in the digital era. This handsome production, a 200-page,

50-year retrospective of German travel photographer and university professor

Harald Mante, is a paean to Kodachrome, his film of

choice for both personal and professional work. "Paean"—the word itself is

ironic, considering that this first commercially viable color film was

primarily developed by Leopold Mannes and Leopold Godowsky, an unlikely pair

of classical musicians and amateur photographers, in the mid-1930s.

), is its title—not a

little ironic in the digital era. This handsome production, a 200-page,

50-year retrospective of German travel photographer and university professor

Harald Mante, is a paean to Kodachrome, his film of

choice for both personal and professional work. "Paean"—the word itself is

ironic, considering that this first commercially viable color film was

primarily developed by Leopold Mannes and Leopold Godowsky, an unlikely pair

of classical musicians and amateur photographers, in the mid-1930s.

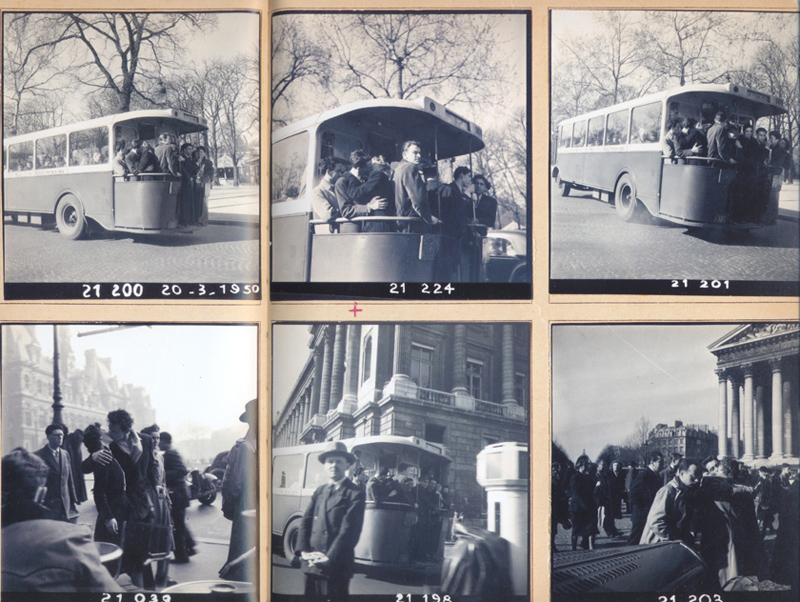

The two Leopolds—"Man and God," as they were called at Kodak—figured out

how to incorporate RGB dye couplers into the processing chemicals, rather

than the film itself as with the now far-simpler to process E-6 films, using

a very complex infusion method that soon utilized an equally complex

selective reexposure on what was essentially black-and-white film stock.

From its beginning, Kodachrome has required very sophisticated processing at

full-fledged labs. But the end result was spectacular: since the color was

not built into the film but added later, actually displacing silver,

emulsion layers could be significantly thinner, allowing for reduced light

dispersion and superior sharpness. According to my 1939 edition of Color in

Photography, by Ivan Dmitri, Kodachrome was manufactured in its early years

with an ASA speed of 8. Not that long ago it was available in E.I.s of 25,

64 and 200. The slower versions offered a grain structure so fine as to be

virtually invisible.

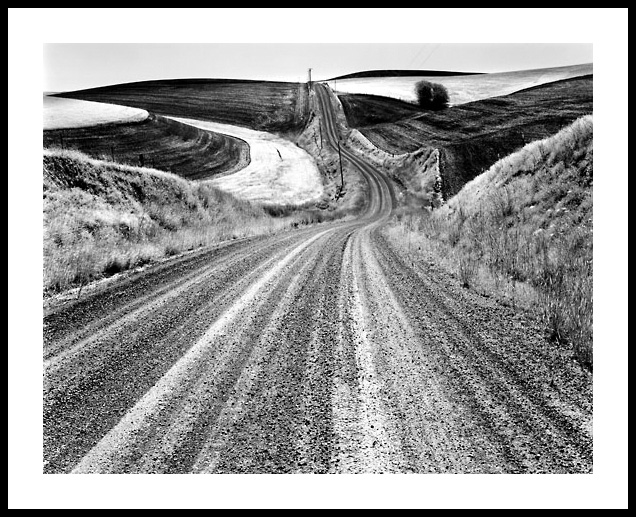

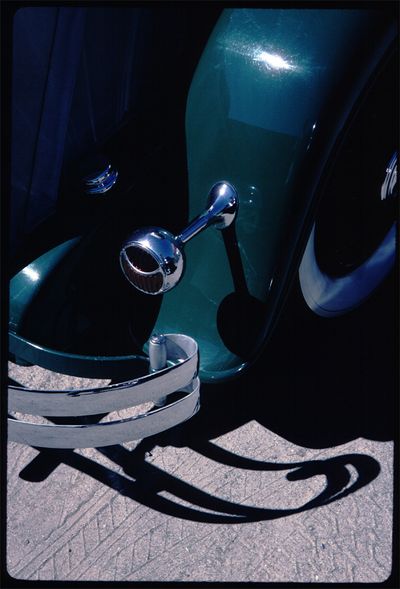

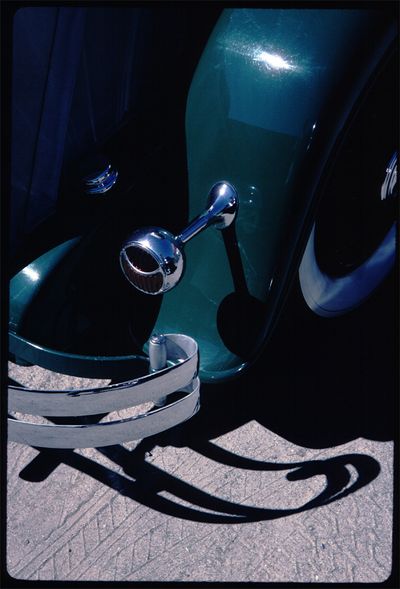

1932 Lincoln Cabriolet, Rockport, Me. Camera: Kodak Retina IIa. Film:

Kodachrome 64. © 2001 by Jim Hughes.

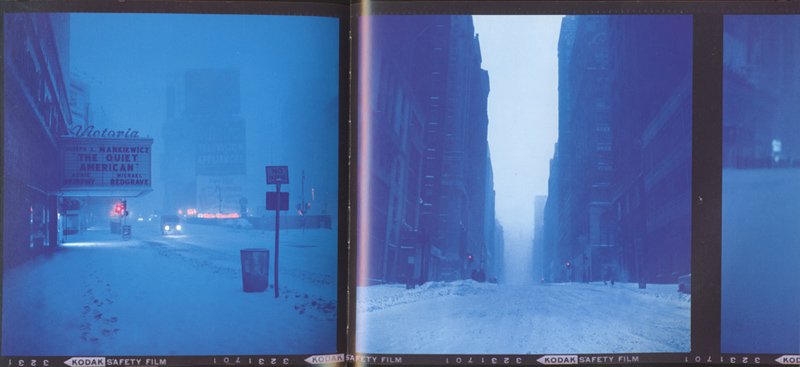

Little wonder magazines such as National Geographic and Holiday for many

years mandated its use by its photographers. Little wonder photographers

such as Sam Abell, Costa Manos, Douglas Faulkner, Jay Maisel, Ernst Haas—not to mention Harald Mante, and yours truly—gravitated to it. But

Kodachrome’s complexity was its undoing. Where once there were labs

throughout the world working around the clock, slowly but surely the

equipment wore out. In the face of a waning markets and disappearing

profits, production lines were not rebuilt or replaced. Dwayne's Photo in

Parsons, Kansas, stands alone today as the processor

of last resort. And when Kodak announced last year it was ceasing production

of K-64, the venerable film’s last surviving embodiment, Dwayne's, with more

than a little regret, said it would shut down its K-14 processing line at

the end of this year.

I had never heard of Harald Mante, or seen any examples of his impressive

body of work, until Mike, knowing my connection to Kodachrome, had Mante’s

book sent to me. It was a revelation (and a little like looking in a mirror,

despite some clear differences in the ways we see). His editor and publisher

(and clearly old friend and admirer), Gerhard Rossbach, wrote in his

forward: "The idea for this book developed during numerous conversations

with Harald Mante about the need to set a counterpoint to the increasing 'homophony' that modern, digital photographic processes produce. Here, we

want to show you Harald Mante's work in its purest form, without the aid of

computers or Photoshop. In other words: what you see here is Harald Mante

unplugged, with each original, unprocessed image showing the moment exactly

as Harald Mante saw it through the viewfinder of his camera."

In a brief statement, "Goodbye Kodachrome," Mante himself says, "Kodachrome

was the first slide film I ever used, and [has] remained my staple for

decades." His book, he notes, is "...a perfect way for me to say 'Goodbye'

and 'Thank You' to this famous film!"

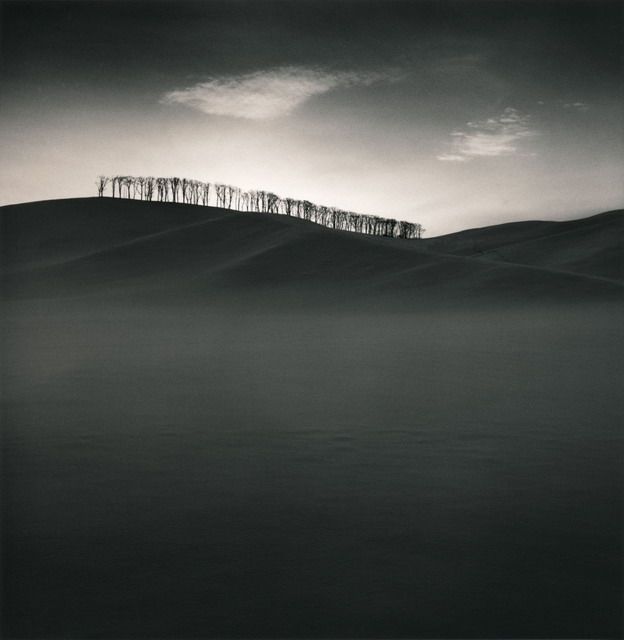

1956 Red Chevrolet Convertible, Rockport, Me. Camera: Kodak Retina IIa.

Film: Kodachrome 64. © 2006 by Jim Hughes.

I have just loaded my final roll into the Retina, appropriate since it was

probably the Kodak camera line that benefitted most over the years from

Kodachrome's original popularity. While I shoot, I will also be trying to

figure out how I will ever match Kodachrome's qualities: that deep, liquid

color, those cool, muted shadows, that wonderful sharpness, the absolute

clarity, the three-dimensional look and feel I've learned to see and

capture. For me, rating K-64 at 100 and exposing for the highlights has

become second nature. Like Harald, for 50 years I have visualized my

pictures in Kodachrome color. Now I’ll have to learn new ways to see.

Jim

Both Kodachrome illustrations are from Jim Hughes' American Classics Series.

Send this post to a friend

Note: Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. More...

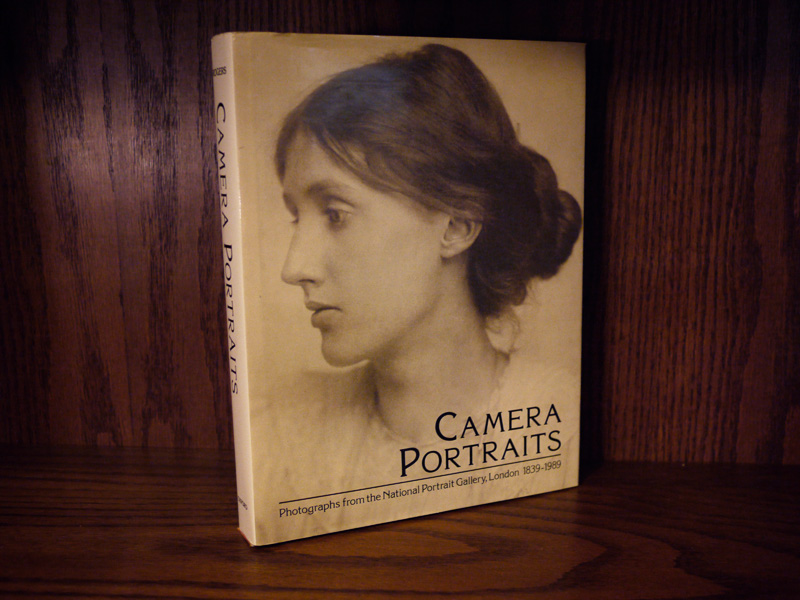

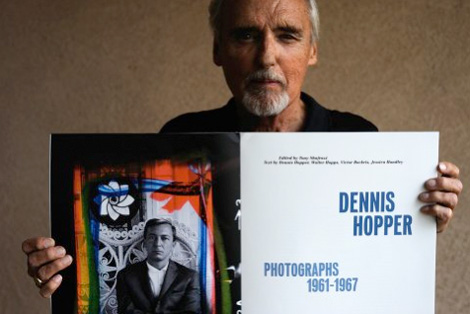

Dennis Hopper with his 2009 book of his photographs. Photo courtesy Taschen

Dennis Hopper with his 2009 book of his photographs. Photo courtesy Taschen, with multilingual text in English, French and German, was issued as a $1,000 limited edition by Taschen in 2009. Another book that covers the same period and includes some of the same work, 1712 North Crescent Heights: Dennis Hopper Photographs 1962–1968

, is unfortunately out of print.