["Open Mike" is the quirky and betimes queer Editorial Page of TOP, in which you indulge Yr. Hmbl. Ed. in his wandering pilgrimages.]

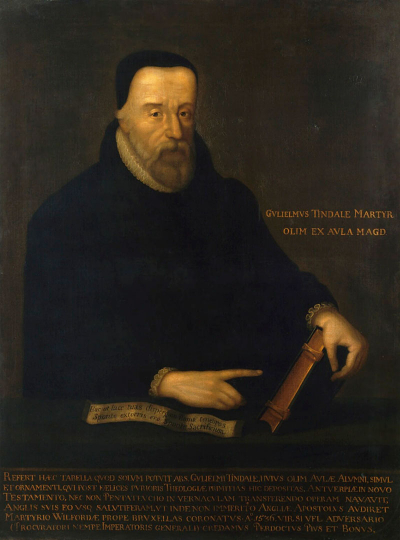

Called William Tyndale [1494–1536]

Called William Tyndale [1494–1536]

Artist unknown, late 17th or early 18th century.

National Portrait Gallery of the United Kingdom.

What Bible would you read if you were going to read the Bible? It's a sign of the times that this can be considered an idle question. It hasn't always been that way. Below, you can read about the fate of the fellow above, for one.

A conservative friend, spurred on by one particular recent development I can't name (you can email me if you really want to know), recently opined at some length that he is against modifying traditional texts. He's religious, and opposes what he understands to be efforts to undermine what the "real" Bible says. "Leave it alone!" he says forcefully. He's of the opinion that the Bible is the Bible, and ought to be eternal. New translations are bunk, hokum, hoo-hah, bushwah. There's only one true one.

Little problem with that. The Old Testament, which is what Jesus would have meant when he talked about "Scripture," was written in Hebrew, with little bits here and there in Aramaic. But the rub is that most Jews in the time and place Jesus lived did not speak or read Hebrew! So the version of Scripture that Jesus himself would have read (if he could read), or quoted (if, as some scholars believe, he was not literate himself), would have already been translated. Into Koiné Greek, the educated language in his culture. Jesus himself would have spoken Aramaic in everyday life. The translation he would have known or known about is called the Septuagint, which was the translation of the Hebrew Old Testament into Koiné—the word means "common"—Greek. The Septuagint was created in the third century B.C. by 72 Hebrew scholars, six each from the Twelve Tribes of Israel, at the behest of the enlightened Ptolemy II Philadelphus. (I can't help a little digression here—"Philadelphus" means sibling-lover: Ptolemy II married his sister, Arsinoe. The word echoes down to our Philadelphia, the city of a kind of brotherly love that is fortunately not so literal.) The ancient books we call The New Testament were written in the first and second centuries Anno Domini, also in Koiné Greek.

Educated Greek speakers today can just about make out Koiné—they take it in school—but not terribly easily or fluently; perhaps, I imagine, like we English speakers read Chaucer. Here's a sample from the beginning of the General Prologue; see how you do:

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his half cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

(So priketh hem Nature in hir corages),

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

(Here's that bit spoken aloud.)

Bifil that in that seson on a day,

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay

Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,

At nyght was come into that hostelrye

Wel nyne and twenty in a compaignye

Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle

In felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle,

That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde.

(Larry D. Benson., Gen. ed., The Riverside Chaucer, Houghton-Mifflin Company)

When April with its sweet-smelling showers

Has pierced the drought of March to the root,

And bathed every vein (of the plants) in such liquid

By which power the flower is created;

When the West Wind also with its sweet breath,

In every wood and field has breathed life into

The tender new leaves, and the young sun

Has run half its course in Aries,

And small fowls make melody,

Those that sleep all the night with open eyes

(So Nature incites them in their hearts),

Then folk long to go on pilgrimages,

And professional pilgrims to seek foreign shores,

To distant shrines, known in various lands;

And specially from every shire's end

Of England to Canterbury they travel,

To seek the holy blessed martyr,

Who helped them when they were sick.

It happened that in that season on one day,

In Southwark at the Tabard Inn as I lay

Ready to go on my pilgrimage

To Canterbury with a very devout spirit,

At night had come into that hostelry

Well nine and twenty in a company

Of various sorts of people, by chance fallen

In fellowship, and they were all pilgrims,

Who intended to ride toward Canterbury.

(Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer Website)

Most modern Greek speakers, I'm told, would still appreciate a translation to read the original New Testament. I appreciate a translation of Chaucer for reading, too. (Here's the one to read, specifically the 2006 Bantam Classics paperback by Beidler, Hieatt, and Hieatt, a dual-language version).

Unlike many Christians (ask them), my friend actually reads the Bible. But since he doesn't read Hebrew or Koiné Greek, which translation of the Bible into English does he consider to be the "real" Bible that shouldn't be changed? There have been between 100 and 250 translations into English, depending on definitions. The definitions include, do you require that the translation has to be complete? Many aren't, including the one I chose. Is it entirely fresh, or does it borrow from previous translations? The Jacobean Bible of 1611—that is to say, the King James Version (KJV) my friend approves of—borrows pretty liberally from Tyndale, there having been no particular squeamishness about intellectual property back then. Things like that.

Tyndale the doomed

There's another little problem, which is that a later major translation, based on the work of St. Jerome in the 4th century, was the so-called Vulgate, which has its own complex history. It's the Hebrew and Koiné Greek Bible translated into Latin. From there, when we come to the early English translations, many of those were based on Tyndale, who was executed for his pains but was good at his work, and Tyndale worked not just from the Hebrew and the Greek but also from the Vulgate and the German Bible to boot. Many English translations have been based on the Vulgate, which various Catholic eminences for centuries promulgated incorrectly as being the original language of the Bible. The King James translation was deliberately based on the Bishop's Bible of 1568, the first Bible in English prepared by a committee. Some scholars have identified as much as 93% of the KVJ as being identical to what survives of Tyndale. From there we can deduce that most of the Bishop's Bible must have come from Tyndale.

So then why read some committee's emendations? Why not go to the source and read the Tyndale Bible? Well, because there isn't one, really. Tyndale was strangled to death for his pains, and his body burned. In strangling him, by the way, they were being merciful to him, sparing him from having to die slowly in the flames, because he was, you know, a good guy. (Another little digression—if you think that humankind is making no progress, consider that States no longer burn people at the stake. Most capital punishments in history in fact were remarkably gruesome; there is a great deal that is humane about that little proscription in the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution against "cruel and unusual punishments," which made its first appearance in the English Bill of Rights in 1689.) Tyndale's death, as you might expect, interfered with his translating endeavors. While you can find scholarly versions of his new testament, in antique English, and facsimiles of his original translation which was smuggled into England, they make rough going now. Many of the books he did complete, particularly the historical books of the Old Testament, are lost.

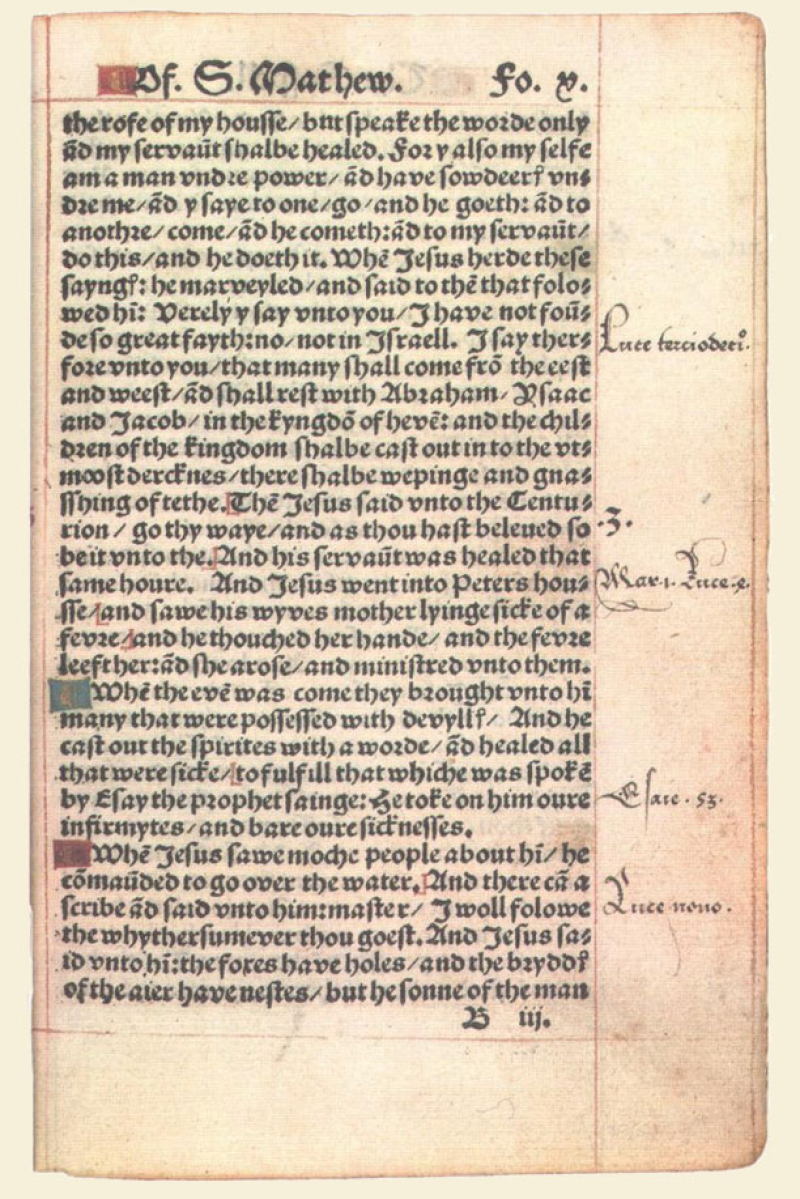

Facsimile page of Tyndale's 1526 translation. Revolutionary then for being written in language that was plain to the common man, it makes tough slogging for English speaking readers now.

I wanted to add more to this for my friend but then ran out of steam. I was getting into the issue of modern translations and their sources, and in some case their agendas. The twin problems are 1.) it's a big enough subject for a good big fat book, and 2.) I'm no expert. I should perhaps add to those two things that I'm not a practicing Christian. But it's interesting stuff. I got into the problem of translation with the Tao Te Ching, which has supposedly been translated into English more times than anything except the Bible. In the case of that book, some "translations" are done by people who don't even speak Chinese! They work from literal meanings of the Chinese characters, or, in some cases, by collating and synthesizing numerous earlier translations. Both of which seem like cheating to me. If you're translating from Chinese, you should at least read Chinese, don't you think? Then again, my longtime favorite version of that book is not a straight translation. It's based on one, by Gia-fu Feng, but he didn't speak English fluently, so it was greatly smoothed-out and made lyrical by its British editor, Toinette Lippe, as she explains in her fascinating Foreword to the 2011 edition.

J(ohn) B(ertram) Phillips

Long story short, unless it's way too late for that, is that my choice for reading the Bible, or at least The New Testament, is The New Testament in Modern English by J. B. Phillips. That's John Bertram Phillips, not to be confused with another John Phillips, of the Moody Bible Institute, who has written reams on the New Testament. An Anglican clergyman, J.B. started his translation to pass the time in bomb shelters during the Blitz of London, writing "for the young people who belonged to my youth club, most of them not much above school-leaving age...I undertook the work simply because I found that the Authorised Version was not intelligible to them." Although smaller parts were published earlier, his complete New Testament was first published in 1958, around the time I was born. More than 10 years later, after his version had become more famous than he thought it ever would, he spent two years minutely revising it for an edition published in 1972. Here's part of what he said of it in the introduction to that edition:

I began the work of translation as long ago as 1941, and the work was undertaken primarily for the benefit of my Youth Club, and members of my congregation, in a much-bombed parish in south-east London. I had almost no tools to work with apart from my own Greek Testament and no friends who could help me in this particular field. I felt then that since much of the New Testament was written to Christians in danger, it should be particularly appropriate for us who, for many months, lived in a different, but no less real, danger...In those days of danger and emergency I was not over-concerned with minute accuracy, I wanted above all to convey the vitality and radiant faith as well as the courage of the early Church. The attempt succeeded and, as I have mentioned in the Translator's Preface to earlier editions, the strong encouragement of C. S. Lewis led me to continue the task.

[...]

I offer this translation as a wholly new book. Having by this time done much collateral reading and learned more of the usages of the N.T. Greek, I felt that now, faced with a completely clean sheet, as it were, I could do a better job. Quite apart from my own feelings there were good reasons for tackling this rather daunting task. The most important by far was the fact, which perhaps I had been slow to grasp, that "Phillips" was being used as an authoritative version by Bible Study Groups in various parts of the world. I still feel that the most important "object of the exercise" is communication. I see it as my job as one who knows Greek pretty well and ordinary English very well to convey the living quality of the N.T. documents. I want above all to create in my readers the same emotions as the original writings evoked nearly 2,000 years ago. This passion of mine for communication, for I can hardly call it less, has led me sometimes into paraphrase and sometimes to interpolate clarifying remarks which are certainly not in the Greek. But being now regarded as 'an authority,' I felt I must curb my youthful enthusiasms and keep as close as I possibly could to the Greek text. Thus most of my conversationally-worded additions in the Letters of Paul had to go. Carried away sometimes by the intensity of his argument or by his passion for the welfare of his new converts I found I had inserted things like, 'as I am sure you realise' or 'you must know by now' and many extra words which do not occur in the Greek text at all. I must say that it was not without some pangs of regret that I deleted nearly all of them!

There was a further reason for making the translation not merely readable but as accurate as I could make it. It has been proposed that a Commentary on the Phillips translation should be undertaken. I felt it essential that the scholars who would contribute to such work should have before them the best translation of which I am capable. I certainly did not want them to waste time in pointing out errors which I had in fact by now corrected! The last, but not least important, reason for making a fresh translation was to check the English itself. It must be current and easily understood, and I must confess that I thought that the twenty-five years since the publication of Letters to Young Churches might have seriously 'dated' the English I used then. With the help of my wife, several friends, including some critical young people, we scrutinised the English very carefully. Rather to my surprise only a few alterations were necessary, and this showed me that the ordinary English which we use in communication changes far more slowly than I had imagined. I knew, however, that slang and colloquialisms change rapidly, but since I had used few of these there was not much to alter.

J.B. Phillips' comments on communication, which I have bolded above, match my own values pretty well. And they echo William Tyndale's mission precisely: Tyndale wrote that if God were to spare him, he would enable "the boy who drives the plow" to know more of Scripture than the educated clergy does. He died for serving that cause. At any rate it's Phillips' 1972 version I read, and I'm satisfied with the choice, much as I might harken to the echoes of the fated William Tyndale reverberating to us across the reaches of time, through the KVJ and its influences, the beauty of his prose, in places, unimprovable.

Not an easy or a simple matter, Bible translations. My friend's umbrage aside, there's no one "real" Bible in English, much as he might wish there were. The one begun in the bomb shelters during the Battle of Britain to communicate to the youth of that time serves fine for now.

Mike

*Education means primarily gaining knowledge and information, while edification means something more like improving oneself morally and spiritually. I had to go look up the distinction.

Original contents copyright 2025 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. (To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below or on the title of this post.)

Featured Comments from:

Have you encountered ‘A History of the Bible’, by John Barton? It is, as its title suggests, an account of the creation of the Bible(s)- when the books were written, by whom (as much as is known), where, and in what context. It includes both the Christian Bible - that is, the New Testament - and what the author refers to as the Hebrew Bible (what Christians term the Old Testament). Plus all the formal apochryphal content, plus many other writings that didn’t make the cut when the definitive versions were agreed, plus more recently discovered writings, e.g. the Dead Sea Scrolls.

I found it to be a fascinating book. The author is a Christian and a theologian, but the book is not intended to proselytise. Recommended.

Posted by: Tom Burke | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 09:48 AM

Mike, you assume that the 'person Jesus' is a historical figure, someone who like Pontius Pilate then actually lived (whether he was a god or not is irrelevant). There are, or exist no texts (or artifacts) from that time period that show or prove this, not in the Vatican or anywhere else in the world. This Jesus belongs to faith, not exact science. The biblical texts originated 200 years after dato ..., don't you know this?

Posted by: Jozef | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 09:56 AM

Well...this is an interesting one. I think there are 2 bibles to consider. The first is the interlinear bible, in which the original languages are right there with the translation in alternating lines. But that's one for someone who wants to do the extra work of digging into those languages.

The second---best for most people--is the Parallel bible, which has 4 translations laid out across the pages. With this bible readers don't have to get into the weeds of the original languages, but can see immediately how different translations can subtly (or not so subtly) affect the meaning or at least the weight of the words.

But the faithful should be forewarned: the more you learn about the bible and how it came together and the historical contexts in which it was written---particularly true for the old testament---the more doubts you may wind up having about the sacred-ness of it all.

Posted by: Tex Andrews | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 10:10 AM

A history of the preparation of the King James Version is found in Adam Nicolson’s “God’s Secretaries”. It’s a fascinating read. The NRSV (New Revised Standard Version) is what I read on those rare occasions when I read the Bible at home. I’m an Episcopalian, and we use the NRSV in Church. Since Episcopalians are basically Anglicans, we’re entitled to say “you’re welcome” when someone claims that the KJV is the only true Bible; but we’re too polite, so we only think it.

Posted by: Mark B | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 10:58 AM

A fascinating glimpse into a complex topic, Mike.

I highly recommend the modern translation of the five books of Moses by Robert Alter. The language is lovely and powerful, with very interesting commentary on the words and phrases being translated (and sometimes the difficulty of translating them):

The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary by Robert Alter

Posted by: Tom Passin | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 11:01 AM

The changes in English between Chaucer's time and ours are quite obvious. But there are also more subtle changes in things like word meanings that even a highly educated English speaker might not recognize. One of these came to my attention a while back: the word "prevent". Today it means to keep something from happening. Its archaic meaning, though, is "to go before" as well as a few closely related meanings. So the a traveler might say to his companion, "Prevent me at the inn and reserve a room." That is, "Go ahead of me to the inn ..." The word "prevent" occurs 7 times in the KJV, with an additional 9 instances of "prevented" and one of "preventest". A modern reader, unaware of the change of word meaning would either completely misinterpret these instances or at the very least find them confusing. Here's an example: Psalms 119:147 "I prevented the dawning of the morning, and cried: I hoped in thy word." Certainly the writer didn't stop the dawn from occurring. Only the archaic usage makes sense in this context. I'm sure there are other archaisms in the KJV that I'm unaware of, equally able to trip up a modern reader.

Source note: I've taken the usage counts from https://thekingsbible.com/Concordance and used the link there for the example quoted.

Posted by: Bill Tyler | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 11:01 AM

It probably depends on why you are reading it. I'm not a Christian, but I am interested in English literature and the King James version (often incorporating turns of phrase from Tyndale) is the one with which subsequent novelists, poets and playwrights were familiar with. So if you're reading the bible for literary reasons, King James seems the one to go for. (It also happens to be the one on my shelf, because given to me as a small child. I'm unlikely to invest in another version.)

Posted by: Chris Bertram | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 12:04 PM

Splitting Hairs-

from the series, "Churches ad hoc".

Posted by: Herman Krieger | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 01:02 PM

I am not a native English speaker and only culturally christian, if even that. But if I read an English translation, I would read the KJV. I would do so because I think that the English spoken and written by people in and around London in the late 16th and early 17th century is uniquely resonant to at least British English speakers today. It is far enough away in time to sound strange, yet still close enough that, with some work, we can read it without great effort and understand its allusions. That is not true for Chaucer, whose language and world is now too distant from us.

I do not, of course, believe that the KJV is somehow unique among translations. But there is other work in English written at that time for which we know that there is a unique original even if, perhaps, we do not quite have it. And that work, also, is both readable without great effort and, to modern British English speakers, extremely beautiful:

Even with the original orthography and punctuation this is readable today. And there is no more beautiful English than this.

Posted by: Zyni | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 01:21 PM

There are so many bible translations. Formal Equivalence and Dynamic Equivalence, and everything in-between.

I personally view the bible as literature and prefer dynamic equivalence, which would be what J.B. Phillips has written.

Good OT today, thanks.

Footnote: I like the version of the Tao Te Ching by Stephen Mitchell. But, I like to read multiple versions. I've heard good things about the Jane English version, and will check that one out. I'm also going to read Ursula LeGuin's version. I don't worry too much if the writer can read or write Chinese due to all the available texts, it's the interpretations that are interesting to read.

[Jane English was the photographer. She didn’t have anything to do with the text. The translator was Gia-fu Feng and he did the calligraphy, and Toinette Lippe is the editor and de facto co-writer. —Mike]

Posted by: SteveW | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 01:40 PM

Good. Be you.

Posted by: DZ | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 02:10 PM

Speaking of translations... If you haven't already, check out "English as She is Spoke" by Pedro Carolino. It's alleged to have had major fans in Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain. I wouldn't be surprised if Monty Python found inspiration in it. It's in the public domain and available from the usual sources.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_as_She_Is_Spoke

Posted by: Roger | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 02:14 PM

I too have wondered "which" bible translation to read.

I read this article in The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/08/28/why-the-bible-began-an-alternative-history-of-scripture-and-its-origins-jacob-l-wright-book-review

Really informative of how the Bible was written to endorse one particular view of the tribes, wars, and conquests of the region. The article is very much worth a read.

Very interesting article, so I bought the book. I gave up half way through the book, too much detail. Eyes glazing over.

The book: https://www.amazon.com/Why-Bible-Began-Alternative-Scripture/dp/110849093X

Posted by: John Shriver | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 02:36 PM

Cannot say I'm into the bible at all. Or for that matter, religious texts in general. Too many wars are fought over self-serving ideologies, land and gold in the name of "god."

There are tons of great fairy tales worth reading.

Posted by: Bob Rosinsky | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 03:27 PM

Well King James had an interest in preserving property rights and the legitimacy of hereditary kings to be the head of the church, which the KJV is soaked with for one thing. Being the king of both Scotland and England which were still separate countries and wanting to unite them was another agenda.

Posted by: hugh crawford | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 04:03 PM

My father was a Southern Baptist minister in Texas. He read the Phillips translation for his own study. However, from the pulpit, he quoted the KJV, of course. He also had a book with six versions of the New Testament in parallel columns. Individual verses didn't always agree.

Posted by: David Brown | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 04:07 PM

In whatever version or translation, the bible:

1. Is a most comprehensive history book that describes the beginning of the world and until its end. No other history book comes close to it.

2. It deals with the matter of evil that exists in this world today and provides the reason (some call it sin) and the solution to that.

Posted by: Dan Khong | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 04:10 PM

I remember a story in which a woman said, "If the King James Bible was enough for Jesus, it's good enough for me."* And that's all I have to say on that subject. ;)

* Apocryphally attributed (in a different formulation) to Texas governor Miriam A. ("MA") Ferguson. The sentence's utterance may be an urban legend. But it illustrates the point so nicely, one wishes it to be true.

Posted by: Benjamin Marks | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 04:42 PM

A very worthwhile Sunday "read", well-written and well-argued. Thank you.

Posted by: Joseph Kashi | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 04:47 PM

Try David Bentley Hart's translation of the New Testament. It's not a woodenly literal translation, but he tries to render the English in a way that reflects how the Greek would have been heard by original audiences. So, for example, you can clearly see the weird changes in tense in Mark's gospels, or Paul's paragraph long sentences in his letters. You can see in the translation which of the New Testament authors were more educated and which ones were writing in simple, even clunky Greek. Some words he either leaves untranslated or renders them in 'non-standard' ways to try to get around how many of the terms have taken on later theological significance that were probably not there originally. I find it illuminating.

Posted by: Aaron | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 05:09 PM

I’d read a Bible called Braiding Sweetgrass:

Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Posted by: Simon Griffee | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 05:14 PM

Your comment about there not being a “real” English bible is too simple by half. There are dozens of them, in reality. From translations based on the Textus Receptus (as is the KJV - but one must read the preface to that translation by the translators to appreciate), to those from the later critical text, and majority text, the message of the bible is clear and unambiguous. (What one thinks of that message, and does or does not do about it is an entirely different subject.) The huge repository of manuscripts, and the careful analysis of textual variants, has--rather than demonstrated unreliability--confirmed amazing concordance. Add in the fact that the underlying manuscripts come from “all over the place” in time, geography, and cultural milieu, and it is impressive. These comments, of course, apply principally to the New Testament, but there are concomitant comparisons between the extant OT manuscripts.

Posted by: Rand Scott Adams | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 06:55 PM

A tangent off Tyndale… last year, the whole year, I read the Wolf Hall trilogy (Hilary Mantel) via a “slow read” by Simon Haisell at Substack (https://footnotesandtangents.substack.com/p/wolf-crawl). They are quite distressing, especially when you know all the inevitable dooms coming (and their awful motives and means). And also brilliant and remarkable and Hilary Mantel’s death is a great loss of a brilliant and remarkable person. I recommend Simon’s readalong, which is so sympathetically informative, but if that’s not a course of reading that interests you, I recommend the books anyway. “Translation” is, to me, a fulcrum on which that historic world (and its subsequent present) is leveraged; Tyndale, though not directly present, the lever. Honestly, Mike, I think you’d love the readalong, which helps manage and inform the reading (it’s not something I thought I’d like, but Simon is a delight).

Posted by: Marc | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 08:02 PM

On the subject of the bible, I recommend "The Closing of the Western Mind". The (christian) bible is not the main subject of the book, but the account of how politics played a central role in determining the "official" version is fascinating.

Posted by: Yonatan Katznelson | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 09:46 PM

OT ... NT

Posted by: Nicolas | Sunday, 02 March 2025 at 11:14 PM

Gideons - because I would be in a motel room and bored buttless.

Posted by: Arg | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 01:47 AM

Anything old and from different cultures and languages always presents a problem to modern readers. As you and some other commenters have already mentioned there are differences in even old and modern English. Add in the fact that even modern languages there are words in one that don’t have direct translation in another. Complicate things even more when you realise things we take for granted now may not have been common knowledge in times past. Mathematical concepts such as zero infinity and very large numbers aren’t as old as the Bible! Was 5,000 just an old fashioned way of saying ‘a lot, too many to count’?

Posted by: ChrisC | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 01:56 AM

https://www.recoveryversion.bible

Posted by: Eben | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 02:48 AM

Something I blogged a decade or more ago (sorry not to condense it a bit):

It has been suggested – utterly without supporting evidence, and unlikely as it seems – that Shakespeare might have lent a hand with the wording and meter of the Book of Psalms in the King James Version of the Bible. Well, OK, an awful lot hangs on that "might". But, just suppose that in 1610, when the Bible was within a year of publication, the members of the committee of translators had reason to thank and surprise him on his birthday. He would have been forty-six years old that year, so let's just pretend he was invited to examine the final text of, shall we say, Psalm 46?

So, take a deep breath, and imagine further that he was prompted to count to the forty-sixth word from the beginning, and to the forty-sixth word from the end (ignoring the title and the "selahs" – words signifying pauses or rests). Get a King James Bible, and count them for yourself, and you'll find in line three the word "shake" and in line nine the word "spear." Moreover, in the way of these numerological things, if you then add the 4 and 6 of forty six, you get 10. The tenth word of the tenth line is "will". Curious, no?

It is all nothing more than a complete coincidence, I'm sure. But that would have been quite an ingenious birthday present, even – or maybe especially – if unintended. Of course, it's not impossible that – if Shakespeare had any role in the polishing up of the Psalms (which, let me repeat, is not known and is highly unlikely) – it is a present Shakespeare might quietly have given to himself. These are often the best presents, after all. Yet another new quill is all very nice, thank you very much, but to create for yourself a personal secret hiding place in what would become one of the greatest bestsellers of all time would be rather satisfying, wouldn't it?

Here is one more intriguing fact (allegedly – I haven't had the opportunity to check for myself, and I'd be grateful for any eye-witness corroboration). Apparently, the KJV Bible on permanent display in Stratford church has been open at the pages containing Psalm 46 for as long as anyone can remember. Again, if true, it's probably nothing more than coincidence, or even the work of some conspiracy-minded or mischievous cleric. But a birthday should be the occasion for a little harmless fun, and it's nice, isn't it, to see the right name elegantly concealed in plain sight, rather than all those tedious de Veres, Bacons, and the rest?

Posted by: Mike Chisholm | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 03:53 AM

I've made this decision twice. First, as an undergraduate at a Christian college where two semesters of bible study (old and new testament) were required. I chose the NIV because I found the translation approachable and because I found a nice copy for a reasonable price at Waldenbooks.

Much later, as a graduate student, I decided my only interests in the bible were literary. The Geneva Bible was the bible of Shakespeare but, at least in the United States, either the King James or the Douay Rheims are much easier to find. And all are heavily based on Tyndale.

My favorite Tao Te Ching is by Ursula K. Le Guin. She freely admits it is a version and not a translation. But it was a book she grew up with and it is lovely to read.

Posted by: Philip | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 10:31 AM

Bravo, Mike for publishing a post that should just be an essay on translation and faith and whatnot, but runs the risk of being seen as… well, you know.

As to which translation I’d read, it would be whichever is easiest for the modern reader to get through. I struggle even with Victorian-era classics for their bombast and lily-gilding, so Biblical passages tend to put me to sleep before the end of the first paragraph.

But I am interested in the content. Not as a believer – I’m an atheist but not a hater; I have great respect for the Bible and all of the Abrahamic religions for their place in human (western) cultural development and progress. I wish I knew the Bible better, although when I hear from people like your conservative friend I sometimes think I already know it better than they do (for reasons such as the ones expounded in your post).

It’s sad that so many among the faithful are so incurious. There’s a great line in the movie “Conclave” where the man in charge of the process of picking a new Pope says “Our faith is a living thing precisely because it walks hand-in-hand with doubt. If there was only certainty and no doubt, there would be no mystery. And therefore no need for faith.”

I also think of a anecdote relayed to me recently where an American so-called Christian was complaining about something or other (something he deemed “woke”) and it was demonstrated that it directly corresponded to the teachings of Jesus. The man’s reply was “well that’s weak and it should be changed.”

Posted by: Ed Hawco | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 12:15 PM

My son (age 16) showed me this Video the other day: https://youtu.be/RB3g6mXLEKk. It shows two guys competing on Bible knowledge on a TV show, and I think it makes your point very well, Mike :-)

Posted by: Soeren Engelbrecht | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 02:51 PM

I really like Sarah Ruden's "The Gospels: A new translation" She approaches it with a new eye that was trained on translating the classics.

Posted by: KeithB | Monday, 03 March 2025 at 03:01 PM

The process of the Bible curating and editing through the first millennium is the subject of a whole chapter in Harari's last book, Nexus, about the flows of information through history. A very interesting read, and to me maybe much more than the Bible itself.

Posted by: Nikojorj | Wednesday, 05 March 2025 at 12:29 PM

I've been talking with my wife about us becoming expats as well. Portugal is high on the list, though neither of us have ever been there. We're planning to visit in the next year or so. I hope language won't be as difficult a barrier as we imagine, because English is widely spoken there, especially among the growing expat community, and our phones can translate for us pretty well.

We haven't considered Ireland or the UK yet, but I do have English and Welsh ancestry and the language barrier would be lower by default.

The real daunting challenge is the thought of packing up and moving to a completely foreign place, especially since we have family and pets to consider as well.

Posted by: Michael | Wednesday, 05 March 2025 at 01:19 PM

Its not just that we dont have an original version of the bible in English, we dont have an original Koine Greek NT. As Bart Ehrman says: "I did my very best to hold on to my faith that the Bible was the inspired word of God with no mistakes and that lasted for about two years [...] I realized that at the time we had over 5,000 manuscripts of the New Testament, and no two of them are exactly alike. The scribes were changing them, sometimes in big ways, but lots of times in little ways. And it finally occurred to me that if I really thought that God had inspired this text [...] If he went to the trouble of inspiring the text, why didn't he go to the trouble of preserving the text? Why did he allow scribes to change it?"

Posted by: Ritchie Thomson | Wednesday, 05 March 2025 at 03:37 PM

KJV. “ Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.” Ecclesiastes 9:10. It is compact, devastating, beautiful; and the poetry allows ease of remembering.

The next verse sobering too: “I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.”

Posted by: Richard G | Wednesday, 05 March 2025 at 05:41 PM

After discovering a copy at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, several years ago, this one:

https://saintjohnsbible.org

...for the pure visual pleasure.

Posted by: Merle | Thursday, 06 March 2025 at 09:03 PM