One more post about this (to those of you waiting for me to move on*). I confess it's probably more useful for younger, newer photographers...who aren't reading this. But oh well.

The A.S. and the wall placard

I said the other day that "an idea is any intellectual notion that facilitates and motivates working," and Gary Nylander very sensibly brought up the topic of the artist's statement. I'll abbreviate it "AS" for this post, although that's not a standard abbreviation, so don't use it in the outside world and expect it to be understood. To the AS I would conjoin the "wall placard," those often exquisite orchids of text that are put on cards and sprinkled amongst the pictures at an exhibition. The AS is more closely related to the wall placard than it is to a working-process idea.

I take a somewhat jaundiced view of artist's statements, that woeful sub-category of compulsive literature cheerfully lampooned by the phenomenon of the "artspeak generator" and IAD, international artist dialect, but I love wall placards, usually the responsibility of the curator of the show you're looking at. Szarkowski used to write some of the wall placards for MoMA shows, can you imagine? That's a bit like Édouard Manet drawing New Yorker cartoons. I wonder if those were properly cherished and preserved. (Why do we still not have a collected writings of John Szarkowski? That's a scandal.) Many times, the wall placards are plucked from the exhibition catalog, and are preserved in that manner. Wall placards give added information about the work, from a more objective and more professional perspective, and their presence ranges from neutral to positive, in my opinion, as a component of museum shows; they never detract, as you can ignore them if you wish. Most museumgoers ignore them, I feel like. But my heart sinks a little if I look around a gallery room and see no wall placards. (Some of which are painted right on the wall itself. How do they do that?)

So, are the working idea and the artist's statement the same thing? No. The AS is usually a back-formation, created to justify the work after the work exists. They're meant to imply that the work is deeper than it looks and also that the work lives up to the artist's intent. They also are probably meant to signal [verb] that, if the viewer might not like the work, then the viewer might not understand the work.

My signal [adjective, meaning "striking in extent, seriousness, or importance"] example came from a group show I saw many years ago. One participant had photographed...bramble. Tangled branches of bushes with no foliage. The tangled, twisted, interlaced stems filled the frame and showed no surrounding context. Some from a little closer up, some from farther away, some in hard sunlight, some in soft overcast; and so forth. So they're just pictures of bushes. It wasn't enough of an idea for one picture, much less twenty-two or whatever. But the fellow had constructed the most elaborate and convincing apologia for what he had contrived to do that I couldn't help but admire the chutzpah. It was so clever, so compelling, so convincing, so insistent, that it made me see the bramble photos in a more sympathetic light...for a while. Then I went back to the more clearheaded reaction that the fellow had had no clue what to make pictures of.

Which gets us back to the idea of the idea. (Sorry. I've known that was coming.) An idea is any intellectual notion that facilitates and motivates working, but here's the thing about the idea as the framework, the "bones," of a project, theme or mission: the quality (subtlety, erudition, nicety) of the idea often doesn't have a direct correspondence to how well it will work. A dumb idea can lead to great pictures and ongoing growth, and brilliant-sounding ideas can lead to dull pictures or dead ends. Many times over the years I've questioned photographers about what they were up to, and often they give simple, unsatisfactory answers. One's crest falls. Ideas are not always good. Or smart, articulate, or well-conceived. Academic people have the most trouble with this, because they're trained to work with ideas and they're well aware of the beauty ideas can have; and they're afraid of stupid ideas—having long since learned the trick, crucial in academia, of not looking stupid. They will often construct beautiful, intricate, dazzling ideas...and then, from it, create bad, weak work that trails along behind like an unwilling child.

Because here's the thing: you can't evaluate a working idea for art by the usual standards. An idea is good if it facilitates and motivates working, so that's how you have to evaluate it. I mentioned William Wegman the other day. What was his idea? Presumably it was something like, "I'm going to make a portrait of my Weimaraner dog." On its face, that sounds like the dumbest damned idea for a photographic project anyone's ever heard. But it has literally inspired a lifetime of work, and that work has earned acclaim, renown, remuneration, and Guggenheim Fellowships. He's been endlessly creative in thinking up new ways to make pictures with the dogs in them. It was therefore not a dumb idea. It was a fantastic idea. It hasn't even been copied: Weimaraners belong to Wegman. It has proven infinitely flexible, consistently enabling, and unaccountably rich. But will "I got bored and started taking pictures of my Weimaraner with a hat or a tie on" do, at all, as an AS? Of course not. For that we need something a good deal more highflown.

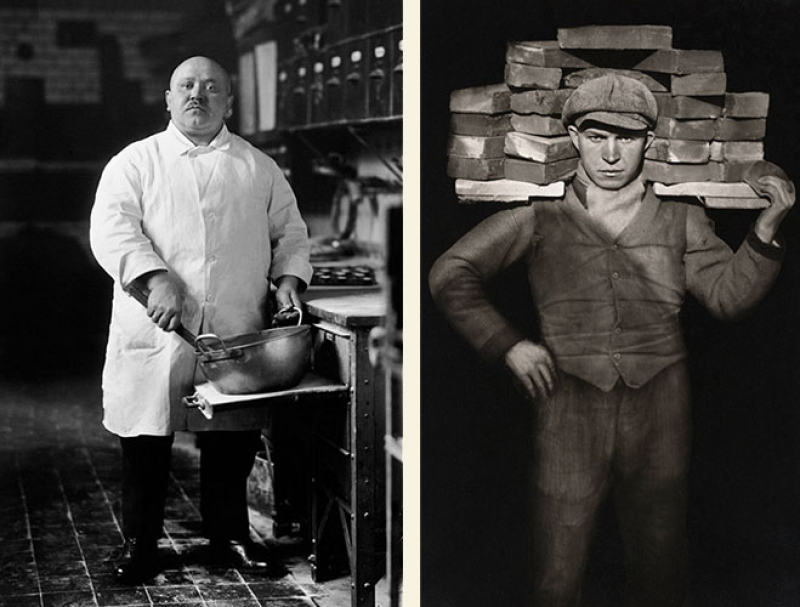

August Sander, Pastry Chef (l.), Bricklayer (r.)

Or take August Sander. His idea was to make an extended typology of the German people during the interwar period, the period of the German Republic—as if people were defined by their work and "types" gravitated to specific work. According to a page at Tate Modern, "He believed that, through photography, he could reveal the characteristic traits of people. He used these images to tell each person's story; their profession, politics, social situation and background." Again, kind of a blunt, even misguided idea. Photographs do not actually tell all those things. But it launched him into working at portraiture, to looking for his "types" and examples of his categories, and set him to roving far outside his normal circles for subjects; with the result that he created one of the great bodies of work in the history of photography. Although the bricklayer might have been interchanged with the pastry chef and none would have been the wiser**.

'Caught my eye'

One final example: I've observed that a lot of part-time digital photography enthusiasts don't want an idea, because they think it will hamper their freedom and constrain their activities. They want to haphazardly grab any "photo opportunity" that happens to pass their way. Which, if that's what you want to do, that's fine with me; you own your own photography. But it's pareidolia one day, a sunset the next, an architectural detail here, a bride in the park there. (Not to forget the quintessential: flowers and cats.) And they'll say something like, "I just take the camera when I go for a walk and photograph anything that catches my eye." That seems like a dreadfully weak-dishwater idea for working, a framework for little more than desultory camera-pointing. (I confess to never having liked the phrase "caught my eye.") But then, consider Henry Wessel—wasn't his whole life's work really just "what I saw on my walk"? He worked incredibly hard at it: putting high mileage on the ol' shoe-leather, photographing persistently, editing thoroughly and all the way to the conclusion of the finished fine-art print and book after book. And, sure enough: "The world is filled with incredible things," Wessel said. "So I’m happy to just let my eye be caught by something. If something catches my eye that’s enough reason to take the picture." He said that. (Of course it was further honed.)

tl;dr: evaluate your own working idea not by its beauty or how profound it sounds but by how well it works for you. A good idea enables and inspires. It has flexibility and adaptability. And consistency; it keeps on working. It lasts through time and keeps you motivated to pursue it further. It promotes creativity rather than stifling it. It gives your photographing direction and a framework (its "bones" as I started out calling it), a purpose, and richness.

What, me worry?

Yeah, I know, we all think we can photograph anything. August Sander's work included landscape, architecture, and nature. But it might as well not have. As a quick litmus test, I'd say you probably don't have a working idea yet until you recognize pictures you might take but that don't fit. A list of "I do this too" categories. To do something in addition to the main stream of your work, you need your work to have a main stream.

And don't worry about the AS. That can be constructed after the fact. If it's ever needed at all—being honest, the world seldom cares. How many photographers are shown in museums? 0.01%? As many as that? The working idea doesn't have to justify or explain you. It can be deep and/or smart, why not, but it doesn't have to be. It just has to rev your engine and get the camera in your hand, and result in the kind of picture that hits the spot for you. And do it again tomorrow. And the next day. Those who find an idea that becomes a style that becomes a signature that becomes a lifetime's work are the lucky lotto winners.

As before, these thoughts are not prescriptive, merely a quick attempt*** to be descriptive. If they lead to any thoughts that help you, then good; if they don't, don't worry about it. I'm just frinkin'.

Oh, and I actually have one more thing to say about bones. I'll try to intersperse something else in between, in the meantime, in case you are bored.

Mike

*I sometimes have a hard time getting off a topic, and I know it. I get enthusiastic. I want to take a deeper dive.

**I had the idea of taking Sander's idea and turning it on its head. Ed Meese, one of Ronald Reagan's top advisors, once came to the Corcoran School to "volunteer," because his wife was on the Board. They set him to work painting a wall. I thought of taking a picture meaning to title it "House Painter" in a Sanderesque typology of Washingtonians, but the Secret Service wouldn't let me get near him.

***This essay: begun at 9:15 a.m., finished at 11:35 a.m. How good could it be?

Original contents copyright 2025 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. (To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below or on the title of this post.)

Featured Comments from:

Not THAT Ross Cameron: "Thanks for this Mike. That’s what I was getting at with my Q in my Bones Part II comment. Ideas can also be poorly conceived and well executed, and vice versa. OK, so it’s not just me that finds AS and placards sometimes a dense babble. I appreciate I’m not in the art scene, and so might not understand where the concepts and language have been and are going. Your story of the bramble photos reminds me of going to see the Sydney Biennale several years ago. Someone had taken a few black-and-white photos of a large area of grass, either early a.m. or late p.m. There were some mounds, which stood out via their shadows. But there was nothing of interest to catch the eye in these photos—no composition. The placards indicated that an infamous building / institution used to stand on the site. Translation—all idea and no execution. And probably the initial germination of an idea—may not have been well thought through."

Mike replies: One of my critical principles, not very popular or respectable in my lifetime generally, is that a photograph should be good to look at.

In some way. Whatever else it is or does.

To me, one of the glaring weaknesses of some of the work given attention in museums I've seen (not that I see all that much of it), as you point out, is that it's all idea—and the ideas sometimes aren't even good ones. For instance, I saw a show in Chicago of "pictures" that were putatively of the night sky, each one titled with the coordinates of the sky where the camera was supposedly pointed. The "pictures" were all rectangles of pure black. That struck me as wrongheaded in several ways—for one, you get the joke right away, and seeing multiple examples of it across a whole exhibit didn't amplify or clarify anything; next, it deprives a real photographer of attention from the institution (in diets this is called displacement—one of the reasons for eating lots of non-starchy plants is that they displace less healthy foods in the diet); and it's not accurate, because there is often lots to see in a night sky. I'm sure real astrophotographers would have been greatly surprised to learn that there is nothing to see in the night sky but unrelieved, featureless blackness.

Look at Dave Lumb's Blurb book linked below—that's a modest idea, but it works, in my opinion, at the length of the book he's made, and I've never seen it before. It's a better idea in my opinion than those rectangles of black.

Dave_lumb: "As a UK Fine Art graduate in 1982 I didn't have to write an artist statement. They were never mentioned. So when did they become 'A Thing'? Meanwhile: 'I just take the camera when I go for a walk and photograph anything that catches my eye.' Sometimes that works for me. Something caught my eye and when I saw another example it became an idea."

Mike replies: We haven't talked yet about how we get ideas.

MikeR: "I needed an AS recently in order to submit work to a state sponsored art exhibition. Cripes! Most such statements make me want to puke. But, forced into it, I crafted something that didn't offend me with flowery language, but more or less retrospectively 'explained' how I go about things. My wife, then my daughter, edited and made suggestions. I let ChatGPT have a go at it. The result was partly barfable, but brought in some good points, so I incorporated those, reworked the thing again, and again passed it to wife and daughter for further scrutiny.

"I learned something about what I actually do from this exercise, so it wasn't totally pointless. I've taken to crafting my own wall placards, a 5x6" thing affixed to the rear of the framed work, that borrows a bit from the IPTC standard, with 'Caption' and 'Description' blocks, the latter containing technical details about the piece. Finally, at 83, I feel focused and organized about my photography. Most of it still sucks, but there ya go."

Nick Cutler: "Ideas have you. Long ago, a colleague I very much respected said 'You don't have ideas, ideas have you.' And once an idea has got you it's impossible to ignore; you have to run with it wherever it goes...."

James Meeks: "In museums where I’ve worked, we usually call the wall placards 'didactic panels,' sometimes 'text panels,' meaning they are informative panels, placards, labels, etc. Other institutions may call them something else.

"As for the text painted right on the wall, nowadays it’s typically vinyl cut on a plotter and applied by staff. I did do some by screen print but that was a disaster. There are other methods I’ve heard of or seen but have not tried. The pieces of paper by a work are merely referred to as labels and come in all sorts of forms. Some are short and sweet while others can be fairly long and are typically written by the curator. When you put the works in a gallery, we say we’re doing an install, and when it comes down it’s a de-install. Not a real word except in the museum field as far as I know."

James Bullard: "I hate writing artist statements. They are only done when exhibitors demand them; to me, they are meaningless. The last one I 'wrote' was done using AI. It didn't read much differently than the pap I would have written myself but it caused me much less anguish to produce."

SteveW: "Re 'Caught my Eye': Thank you for this. This is how I am with a camera anymore, and why I switched to using my iPhone as my primary camera. It's always with me, easy and quick to use, and I'm capturing images that I would have had a difficult time capturing with my 'real camera.' It's been liberating and fun. The iPhone images are well into the 'good enough' zone for me. I suppose my genre of work would be snapshots. It's weird, but if I go out with my real camera (Fuji X-T5) it's harder for me to find shots than simply carrying my iPhone (15 Pro Max) and letting the shots find me. I'm not saying I'm capturing anything tremendous, or building any kind of body of work, but it's more fun for me this way. The Happy Snapper."

Dave Millier: "The Royal Photographic Society have the concept of the 'Statement of Intent' in their distinctions programmes:

A Statement of Intent that defines the purpose of the work, identifying its aims and objectives. A cohesive body of work that depicts and communicates the aims and objectives set out in the Statement of Intent. A body of work that communicates an individual's vision and understanding.

"For their ARPS and FRPS distinctions, a candidate submits a portfolio of images along with the SOI. The SOI is used by the assessors to help them judge the portfolio. I think it is useful for the photographer, too, as it focuses their attention on exactly what they are trying to achieve and portray and helps in the decision-making about what images to include and what to leave out. For me, thinking about the RPS approach has led me to shift gears away from shooting individual images that I later attempt to group into genres, to thinking with a project/portfolio mindset right from the start. The SOI is essential to that shift."

Jim Simmons: "Lee Friedlander liked that one of his friends said Lee wouldn't know an idea if it bit him on the ass. He claimed to have no 'ideas' that he worked from, not even any interests. But after years of photos piling up that had commonalities, the photos revealed to him what he'd been interested in. He, like Wessel, just went out into the world and took the photos that presented themselves to them. Of course, they had the talent to see them."

Mike replies: I think Lee is being disingenuous about that. (Which is his right.) He's got his own way of working, but the titles of many of his books describe ideas. And the ideas are easy to see in the work.

Jim Simmons replies: "I don't know, Mike, I'm inclined to accept Mr. Friedlander's statement at face value. A day before your post, I was rereading an interview with Lee by John Paul Caponigro in a 2002 issue of Camera Arts magazine. He was a little testy/evasive with some of Caponigro's questions, but he especially refused to be pinned down on working from ideas. I quote: 'Anything that looks like an idea is probably just something that has accumulated, like dust. It looks like I have ideas because I do books that are all on the same subject. That is just because the pictures have piled up on that subject. Finally I realize that I am really interested in it. The pictures make me realize that I am interested in something.' He continues, 'I hardly ever think about doing work. I think about going somewhere that might interest me.'

"I am currently in the process of creating a monograph of my 1970s black-and-white work, and I'm trying to apply Friedlander's concept of looking at the photos to discover what my ideas actually were, because aside from a few documentary projects, my work tends to be, like Friedlander's and Wessel's, visuals I stumbled across while living my life with a camera slung over my shoulder. The photos are more a framed arrangement of 2D and 3D shapes reflecting light in interesting ways than they are photographs of the actual objects within the frame. I'm only realizing this in retrospect."

Tom Burke: "I've seen some of Sander's images before, and liked them. Like you, I'm not sure his AS stands up. Looking at those two images today, however, what struck me was how both men were being injured by their occupation. The bricklayer is compressing his spine with the repeated weight of those platforms of bricks, and sooner or later his back wouldn't have been able to take the load anymore. As for the pastry chef, I can't help but wonder how long it was before he had his heart attack.... Time and knowledge helps us to see things in a different light."

My wife is a oil painter (mainly) and has had to write numerous artist statements over the years for submission purposes. I think that ASs are something that galleries ask for because they feel they have to but then never read. It's a lot like software documentation in that sense. It is one of the more irritating aspects of making a submission. If I ever had to write one for myself I'd have no idea what to say other than, "I enjoy taking pictures of stuff." I'm sure that would disqualify me, even if the theme was minimalist photography.

Wall placards are interesting. We visit the National Gallery here in Ottawa quite often and reading those placards is such a pain, even when they do contain interesting info. The glasses I need to view that size text at that distance are usually not the same as the ones I need to view the paintings or photos. Also, the placards are often not well lit. Most of the time I give up and just look at the work, saves me a lot of time and aggro even though I may be missing out on a lot of art history.

Posted by: Robert Roaldi | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 02:12 PM

"***This essay: begun at 9:15 a.m., finished at 11:35 a.m. How good could it be?"

Progress.

Things written quickly can have the same value as things dragged for days through the sticky mud of indecision and revision.

Posted by: Kirk | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 04:06 PM

I'd be curious to know how much of this planning might be retroactive? I would love to come up with an idea and pursue it, but I'm not sure if I work that way. I find myself now, 25-30 years in, looking for threads and themes within my work. And threads that may connect work that wasn't necessarily intended to fit together? Is that more typical than the fully baked plan followed by the work?

Posted by: JOHN B GILLOOLY | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 04:41 PM

Hi Mike, Serendipitous timing! I was sitting at my computer trying to write a AS for an upcoming show (due tomorrow), when I read your article. So much in it that I agree with. I and probably many other artists hate writing these - they always sound too pretentious or self serving. This is what I feel like writing at the moment:

"I have been involved with photography for about 55 years. I am an unapologetic generalist who likes to photograph anything – landscape, abstract, travel, wildlife and people (maybe not so much). I hope that I tell a story, invoke memories or stir your emotions. Sometimes I succeed and sometimes I fail miserably. If you like an image, please feel free to buy it (I am a starving artist). If you do not like, then don't(I am not dying YET). In either case feel free to comment.

It is Probably too snarky for the gallery?

[Since you asked (and as you know I have your photos on my wall all year long), I don't think you're there yet. Snarkiness isn't the problem, but it sounds insecure and defensive, like you're uncomfortable being judged. I would just play it straight--explain as clearly as you can what you've done and why. Here's a tip: try thinking of the people who will like your work, and address them. That can help keep us respectful and on an equal footing with the reader. Just my 2¢. --Mike]

Posted by: Gordon Haddow | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 06:52 PM

I have been photographing an annual rodeo in Southern Arizona for 8yrs. But I didn’t start with an idea, it was simply an opportunity to do some general photography. However now I’m thinking a book. The most interesting part of this is how unpredictable and unexpected it is.

I’ve also been photographing a mud hole for five years. Uh-huh.

Posted by: Omer | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 07:26 PM

I’ve followed all 3 parts of “Bones” so far, along the way losing track of what the actual real topic was as the comments diverge from the main thread a lot at times. I got back on track by rereading all 3 parts without reading the comments so that I could follow your particular line of thought through all 3 parts.

You didn’t hint at what the one thing more you want to say might be but I hope that you will say something, even if it means saying two more things rather than one, about the relationship of intention and goals to ideas that facilitate and motivate our work. I think Wegman’s idea worked for him because he used it to create an ongoing series of photos by introducing different joke features into each successive photo and in doing so produced a body of work which gets seen and appreciated. On the other hand W. Eugene Smith started photographing Pittsburgh with an idea and never managed to produce the body of work he intended, he ended up never “finishing the job” he wanted to do. In both cases the idea facilitated and motivated work but, ignoring artistic merit, the work met the photographer’s intent in one case but failed to meet the photographer’s intent in the other case,

I appreciate your comments so far on how ideas facilitate and motivate work so I’m assuming that facilitation and motivation are 2 of the “bones” in your topic but eventually the work should produce something and I think intention and goal setting are essential and so far unaddressed “bones” to be considered.

Posted by: David Aiken | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 08:58 PM

Hmmm. Whether you like the phrase or not, I seem to remember a post or two of yours about an image that "caught my eye." I think it's a reasonably valid artistic philosophy, myself. In my mind, more so than coming up with some meaningless project scheme and beating it to death trying to make something of it (like your signal example.)

Posted by: Merle | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 09:09 PM

***This essay: begun at 9:15 a.m., finished at 11:35 a.m. How good could it be?

Reference an earlier post on writing and the time it takes. I believe the quote was along the lines of “sitting down town to write with no idea, and the next thing you know, you’re done.” I frequently find being brought into a thought process early provides more value to me than being presented a completed one.

I’m obviously not a writer. But this got me to thinking about my own challenges. Editing my vision vs. editing my work. Which led me to the realization I would be better served by editing my compulsion to take a pretty picture vs one that interests me maybe be one of the most productive things I could do for my own satisfaction.

Thanks Mike this is why I’ve read your stuff since taking photography classes at Nova.

Cliff

Posted by: Cliff McMann | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 09:22 PM

Answer: pretty darned good. You’re at your best when you keep peeling the layers, folding a few back on themselves and voila, a new layer to explore. Thanks. You know your audience.

Posted by: Richard G | Thursday, 16 January 2025 at 11:18 PM

I'm glad to read that my response to your earlier post, inspired you to write your next blog post, great post I enjoyed reading it.

Posted by: Gary Nylander | Friday, 17 January 2025 at 01:08 AM

My artist statement:

I take photographs to amuse myself as well as the occasional spectator. Exhibiting photographs for mutual pleasure is similar to a comedian telling jokes to an appreciative audience. But comedy is more serious than photography. Viewers who see more in my photographs than I do probably have better vision. Those who see less than I do may be right, and I remain partially open to their criticism.

[I like that! --Mike]

Posted by: Herman Krieger | Friday, 17 January 2025 at 01:39 PM

Just wanted to let you know that I really appreciate this series. You're on one of your rolls, and IMO those can result in some of your best posts. And iterative series are well suited to the blog medium.

There can be very little or very much going on when something "catches one's eye", which is really a euphemism for recognition, whether of something abstract or concrete, whether conscious or not, diligently prepared for for a lifetime, or led to by a guide, or by cliches, or some combination of all the above, and more. There are lots of ways to look at your surroundings, in other words.

Posted by: robert e | Friday, 17 January 2025 at 02:07 PM

Love those photos Dave Lumb!

Posted by: Stan B. | Friday, 17 January 2025 at 03:20 PM

Another thing that I noticed a couple months ago during my first visit to Paris Photo, is the "unique idea" is often on the print/output/display end. I certainly left feeling that this narrative, the story behind the photographer or the photographer's process was at least as important as the photography. And while in some cases I think the narrative is so forced as to be ridiculous, I am not saying this with negativity. During tours where I had a chance to listen to the artist or curator, in many cases it did give me insight into the work that helped me appreciate it in context.

Posted by: JOHN B GILLOOLY | Friday, 17 January 2025 at 05:02 PM

“What?! William Wegman got a Guggenheim Fellowship!” I literally said aloud. I mean his work is well crafted but...you must be kidding?

As for the 'wall placard' in shows, I will force myself to refrain from reading those until after I have taken in (and hopefully enjoyed) the work for myself. If I need to go to the placards relatively quickly, then the work is probably a flop. If the art work is good, it doesn't need explaining. Though sometimes an artist statement can add to the work, but I think what one should spend time with the art first. How does it make you feel? What does it bring up? Where does it take you?

I have a theory that the art world has been taken hostage by academia. Perhaps, so that it's taken more seriously in a world which is focused on the objective and quantification. Why does art need to be explained?

Posted by: David Drake | Friday, 17 January 2025 at 11:24 PM

I make photographs of bramble, just as you described. I’m not sure why I do. I guess I just like how they look. I usually find other peoples pictures of bramble fascinating. I also like Jackson Pollock.

Posted by: Eric Lawton | Saturday, 18 January 2025 at 04:06 AM

Thanks Stan B and Mike.

Posted by: Dave_lumb | Saturday, 18 January 2025 at 01:18 PM

Taken as a whole, your original posts, the resulting comments and the back-and-forth are among the best and most interesting work about photography that I've ever seen anywhere on the 'Net. It's very synergistic.

More, please, as time and inspiration permit.

Posted by: Joseph Kashi | Saturday, 18 January 2025 at 05:15 PM

Regarding artist’s statements, there is this analysis: https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1995/07/15

Posted by: jd | Saturday, 18 January 2025 at 09:22 PM

I've just started reading Stephen Shore's "Modern Instances". His introduction does not address artist statements but it does address why and how some photographers have declined to talk about their intentions and work. Those statements seem more to the point to me.

Since Lee Friedlander's comment about how he worked has been discussed, Shore's account of Friedlander's response to the question "What were you thinking when you took this picture?" at a slide presentation of his American Monuments series at Cooper Union might be interesting. Shore quotes Friedlander as saying "As I recall, I was hungry."

Posted by: David Aiken | Tuesday, 21 January 2025 at 02:09 AM

I love your distinction between working ideas and artist statements. I don’t think I’ve seen it put this clearly before, and it’s extremely useful to separate those as two different (maybe completely different) ways to think about a body of work.

However, you are mistaken about the lack of need for an artist statement beyond museum shows. If a photographer applies for almost anything in the “art” sphere (an award, a grant, a gallery show, a fellowship or residency, a teaching job, etc.), they will need an artist statement.

Posted by: AN | Tuesday, 21 January 2025 at 06:41 PM

One of my current series (sounds like I shouldn't have several, but well...) started as a "caught my eye".

Walking about, I saw what looked to me like a face in a tree trunk. Pareidolia. It was fun, I made a photo.

And then decided to start looking for more. And I did find lots more, some I don't care much for and others I like a lot.

But the most amazing thing to me, though I realise I should have expected it, is that they now jump at me! Not literally, of course, but I sometimes see them even when I'm not looking for them. I'm just walking and in the corner of my eye, realise a face is looking at me. But it's not really a face, it's pareidolia. And that happens a lot, now.

So, I started working on a series of pareidolia portraits, for lack of a better description, but I now want to believe I'll find something more than just "simple portraits". And actually have, a couple of times. Two trees were kissing each other. Another two were dancing together.

But boy is it hard to find some that are "more".

Anyway, that's the idea I'm working on. Because I dont have a BA in Artspeak, I call it simply "the tree people". But I'll probably have to work on something better before I can sell it... Won't stop me from having fun working on it, though.

Posted by: Thomas Paris | Thursday, 23 January 2025 at 02:44 AM