By John Kennerdell

A still from "Legend" (2015), Dick Pope, director of photography. In 2014 Pope evidently went through just about every lens at a large London rental house before settling on some old Cooke Speed Panchros for his brilliantly photographed "Mr. Turner." In "Legend," the following year, he switched to Cooke S4s, a more modern design that nevertheless carries on the "Cooke look"—warm and rounded with notably smooth out-of-focus rendering.

-

Introduction, 2017: Thank us or blame us, the notorious b-word first came to the West in a feature in the May/June 1997 issue of Photo Techniques magazine, following a discussion on out-of-focus lens character on the old Compuserve Photoforum. Oren Grad and I pointed out that the Japanese had a term for it: boke aji, literally, the "flavor of the blur." That seemed to grab the attention of the magazine's editor, a fellow called Mike Johnston. He announced that he wanted to do a piece on it. Great, I said, I look forward to reading it. Actually, he replied, I was hoping you'd write it. Oh...well, OK. I'd been in Japan since my student days and had learned most of my photography there, so the subject was certainly a familiar one.

If it had been up to me I might have mentioned the Japanese term once but then called it something in English. (The best translation, in my opinion, came years later from Adobe: "lens blur.") Mike's editorial instincts, however, proved right. For simplicity I dropped the aji, as the Japanese themselves often do, and Mike added a final "h" to make it clear that the word had two syllables. And so a new English word was born, and it was the word that created the buzz.

The concept itself was anything but new, even in the West. Professionals, whether in commercial photography, fashion, or cinema, had paid attention to the defocused parts of their images pretty much since the beginning. But plenty of amateur photographers apparently still felt uncomfortable on the subject of blur rather than sharpness, a concern you can see reflected in the cautious way I wrote my article.

So please enjoy the following as mainly a historical curiosity. After years of hobbyist fascination with ultra-shallow focus (which is not at all what this piece was about), it's amusing to see how exotic the whole subject must have sounded two decades ago. To try to update it a bit, I’ve added new illustrations and captions.

-

What Is 'Bokeh'? By John Kennerdell

Photo Techniques magazine, May/June 1997

Sooner or later, almost all serious photographers come to grips with the question of image sharpness. They learn to evaluate it, and they explore equipment and techniques to help them achieve it. Surprisingly few of us, however, take a similar interest in the opposite of sharpness: the portions of a photographic image that are not in focus. It's a measure of our lack of concern that we don't even have a standard term in English for the fuzzy parts of a picture.

"Blur" comes closest, but covers too wide a territory (for example, motion blur, which has nothing to do with focus). What we need is a word that specifically refers to the qualities that a lens imparts to objects in front and behind the plane of focus.

Fortunately, the land that today gives us most of our photographic hardware has just such a word. The term is bokeh, and to spend time with Japanese photographers is to hear it constantly. They notice it, discuss it, and use it as a basis to choose and use lenses. Magazine lens tests routinely include photos demonstrating it, and certain lenses become renowned for it. In Japan, in short, bokeh is often as important an element of lens evaluation as sharpness, contrast, and all the other hard-edged criteria that we in the West apply to our lenses.

At this point the normal, sharpness-oriented photographer might begin to feel a little uneasy. Surely fuzzy is fuzzy, isn't it? Just how different can one unsharp image be from another?

The answer is very different indeed, once you start to look and compare. In many cases bokeh can be the most distinctive optical feature of a lens—a unique "signature" that appears only once you put away your hyperfocal formulas and open up the aperture. Rollei TLR users have debated the relative merits of the 80mm ƒ/2.8 Zeiss Planar and the 80mm ƒ/2.8 Schneider Xenotar lenses on their cameras for years. Generally they've come to the conclusion that both are outstanding and produce indistinguishable results. A bokeh specialist might politely disagree, saying that the Xenotar tends to slightly elongate out-of-focus highlights. A small difference, and not one that makes either lens "better" than the other, but the point is that even lenses that render sharp images identically will usually reveal themselves in the out-of-focus areas. If you have ever heard of someone squinting through a loupe at a negative and suddenly announcing the lens used to shoot it—the photographer's equivalent of guessing vineyard and vintage—the giveaway was almost surely bokeh.

Interestingly, even photographers who have never considered the issue of bokeh often appear to respond subconsciously to its effects. They instinctively tend to use wider apertures with lenses that render out-of-focus images attractively, and to avoid them with lenses that don't. Have you ever found yourself inexplicably preferring the look of certain photographs taken with a classic camera or even a point-and-shoot over those shot with your state-of-the-art SLR zoom? Look again. Odds are you may be reacting to bokeh.

From Migrations, Sebastiao Salgado. A rare example of selective focus from a man who is on record as saying, "I always close down my diaphragm to give huge depth of field...reality is full depth of field." What’s interesting is that despite the uncharacteristic technique, somehow it’s still pure Salgado.

The good, the bad, and the ugly

So what makes bokeh good or bad? Japanese photographers look for smoothness and naturalness above all. Good bokeh softens objects in front of the plane of focus (mae-bokeh), creating an unobtrusive frame for the rest of the image. Out-of-focus backgrounds (ushiro-bokeh) lose detail but maintain their basic shapes and tones. Good bokeh, like a good photographer, in effect works to simplify images and draw the eye to the main subject.

If good bokeh simplifies, bad bokeh does the opposite. Distracting blobs in the foreground, smeared or jumbled background shapes, choppy patterns of light and dark—these are the sights that make bokeh lovers wince. One common fault cited in Japanese lens tests is ni-sen ("two-line") bokeh: a tendency for out-of-focus objects to separate into two overlapping images. In extreme cases this can make an entire background look as if your eyes have become permanently crossed.

As far as most photographers think about these matters at all, they may associate the out-of-focus character of a lens with with the number of its diaphragm blades. Certainly the shape of the aperture can be seen in out-of-focus specular highlights, and more blades (like the 11 in the Leitz 50mm ƒ/1 Noctilux-M) tend to translate into smoother, rounder bokeh than fewer blades (like the five of the 100mm ƒ/3.5 Zeiss Planar CF, which shows nearly star-shaped out-of-focus rendering of specular highlights). But it's significant that many of the clearest differences between lenses are seen at full aperture, where the shape of the iris is irrelevant. Clearly then, other factors are at work, notably lens coatings (insofar as they affect flare) and optical formula.

Common wisdom in Japan says that good bokeh is most apt to be found in Gauss-derived and other older, more symmetrical lens designs, while retrofocus and zoom formulas seldom deliver first-class bokeh. Yet there are no lack of exceptions. The 50mm ƒ/4 for the Mamiya 6 for instance—a superb, classically designed lens—has received lackluster reviews for its out-of-focus character, while Zeiss zooms for the Contax system consistently win praise.

The irony here is that Japanese bokeh buffs almost universally prefer German lens designs to the modern designs from their own country. One popular theory holds that the remarkable high-resolution, high-contrast "snap" of the great Japanese lenses of the 1960s onward was achieved only by sacrificing the softer, more delicate bokeh that characterized those companies' pre-SLR lenses. In any event, Japan's manufacturers seem to have taken notice. Nikon's DC (defocus control) 105mm and 135mm lenses offer an adjustable moving element to alter bokeh. Canon claims to have paid particular attention to out-of-focus characteristics in the design of its newer EF lenses. And it's no coincidence that the lenses on high-end compact cameras like Minolta's TC-1 and Konica's Hexar mimic the look of the wide-angles that bokeh lovers like best.

From Cuba & Co., Harry Fisch. Foreground blur (mae-bokeh) often gets short shrift in discussions of lens blur. But just look at the dimensionality it can add to an image: focus, lighting, and composition all create a sense of space and lead the eye irresistibly to the main subject. This is also a fine example of what I meant by "rather than totally blowing away a background or foreground...subtly altering it" (see below). When good photographers purposely defocus something, notice how often it still serves as content rather than simple abstraction.

Focal length issues

Then there's the issue of focal length. For bokeh by the bucketful, nothing beats long, fast lenses. This helps explain the huge popularity of 300mm ƒ/2.8 lenses routinely used at their widest aperture for portrait photography in Japan, never mind the need for a bullhorn to talk to your model.

Many Japanese bokeh connoisseurs, however, find this too much of a good thing. Rather than totally blowing away a background or foreground, they're interested in subtly altering it, and it is here that certain lenses in the medium wide-angle to short telephoto range shine. Leica lenses remain a firm favorite among bokeh fans, particularly the 35mm Summicron-M, the 75mm Summicron-M, and the 80mm Summicron-R. Schneider is another much-respected brand, both for its larger format lines like the Super-Angulons as well as its wonderful legacy of lenses for 35mm cameras like the Kodak Retina. Zeiss and Rodenstock have strong followings, as do older names like Agfa, Voigtlander, and Kodak. Among Japanese brands, Minolta enjoys a fine reputation in the 35mm format, while the latest Bronica medium-format lenses are well regarded for their bokeh. But there are many more individual examples from other manufacturers, just as there are particular lenses that excel at sharpness or contrast, or lack of linear distortion, or any other quality.

Does it really matter?

Ultimately, even its Japanese proponents would admit that the beauty of bokeh is in the eye of the beholder. Out-of-focus characteristics of lenses aren't measurable or quantifiable—or at least no one, to our knowledge, has suggested how they might be—nor are they easy to describe in words. Bokeh is essentially an aesthetic judgement, and even photographers who value it don't always agree on its finer points. Where a highlight meets a shadow in an out-of-focus background, for example, some bokeh aficionados like to see a smooth gradation from light to dark. Others prefer a lens that maintains a distinct but somehow tenuous line between the two, a bit like the border where two watercolor washes meet. It's all a matter of taste.

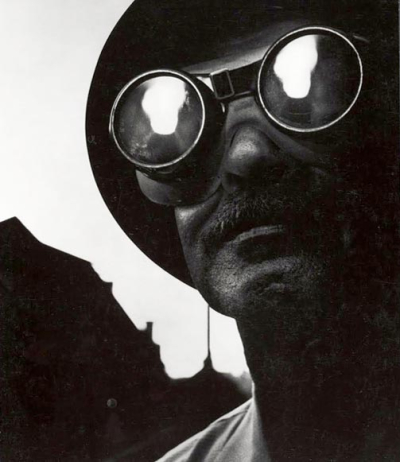

Steelworker, Eugene Smith, 1955. This isn't a very good JPEG—the blacks shouldn't be nearly this blocked up—but it's enough to see how Smith used the steel mill to frame the worker's face and balance the composition. And again, it's sufficiently out of focus to distinguish itself from the main subject, but not so much as to lose its contextual meaning.

Negative space

The particular Japanese sensitivity to bokeh has clear historical roots. Artists in Japan have traditionally believed that the depiction of space around a subject is as important, in its own way, as the subject itself. Where we in the West are inclined to look at a picture and instinctively filter out the "empty" parts, the Japanese approach is to take it all in, enjoying the interplay of subject and space—or in this case, focus and blur. No wonder the character of that blur is of more than passing interest.

For the photographer addicted to overall focus and maximum depth of field, none of this needs to be a concern. However, for anyone who likes or needs large apertures and selective focus, bokeh is not only inevitable but also a valuable, if subtle, aesthetic tool. The sharply delimited plane of focus, after all, is the optical phenomenon that sets photography apart from the other visual arts. We already make conscious use of the in-focus performance of our lenses. Why not do the same for their out-of-focus characteristics?

Perhaps most importantly, bokeh has a way of captivating photographers' eyes and minds once they begin to look at it. And while nobody is likely to argue that an appreciation of of bokeh is required to create good photographs, it nonetheless seems to play its part in some great images. At a recent exhibit, far from Japan with anything but bokeh on my mind, I came across a print of Eugene Smith's classic "Steelworker." Out of focus in the distance is the roof of the steel mill. It is exactly the kind of background that many modern lenses (including the one on the camera slung over my shoulder at the time) would reduce to a drab sort of grayish blob. Smith's old screw-mount Leica lens holds it together in a beautiful, almost painterly way, and in doing so turns it into an effective part of the image. Mr. Smith was not a man to leave either the technical or aesthetic aspects of his work to chance. Even if he didn't know the term, he knew his bokeh.

John

My thanks to John for this whimsical stroll through the past. Neither of us can believe that 20 years have passed! Incidentally, late April—right around now—is about the time that the May/June issue would have arrived in subscribers' mailboxes, and at the editorial office of Preston Publications, Niles, Illinois, which published Photo Techniques. S. Tinsley Preston III was the publisher; Tinsley's father, Seaton, founded the magazine in 1979 as Darkroom Techniques. It ceased publication as of the last issue of 2013, after a good long run. I served as Editor-in-Chief from 1994 to 2000. —MJ

©1997, 2017 by John Kennerdell, all rights reserved

Original contents copyright 2017 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

Journey through the past

Give Ed. a “Like” or Buy yourself something nice

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Benjamin Marks: "I remember well reading this article. It made a profound impression on me as, at the time, I was mildly obsessed with lens sharpness. It was one of those hit-to-the-head moments when you realize you have been charging in one direction with all the other lemmings only to realize that there was a whole culture out there that saw things differently, in 'negative space' as it were. Reading the words above was literally like a crow-bar in my mind and after I read the article I could never really look at the world of photography in the same way again. It has informed the way I look at picture ever since. The best thinking and writing will do that to you, and I am profoundly grateful for it."

John Willard: "Robert Pirsig, the author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, has just passed on to the eternal open road. And hopefully it is a road of good quality. If he had been a regular reader of this site you would have gotten an epic comment from him about this thing called bokeh."

Christopher May: "It's interesting to read the article that kicked off what has turned into almost an obsession. I'm particularly amused by the opening sentence. The whole sharpness quest rages on in this era of pixel-peepery but the same can almost be said of bokeh now. While I occasionally read about other lens parameters that matter, it seems that sharpness and bokeh are now the defining qualities that just about every photographer mentions when discussing lenses.

"I honestly think the bokeh obsession might be even stronger than the sharpness quest now. I'm always kind of amused when people compliment one of my pictures because of its 'nice bokeh.' Um, OK. Thanks, I think. It's kind of wild to me that someone would compliment the picture based solely on one lens characteristic. Can you imagine if a commenter offered praise over, say, distortion? 'Really lovely pincushion distortion!'

"Additionally, I've often found that the comments regarding bokeh are kind of oddly applied. Sometimes they're made on photos from lenses that don't feature particularly nice bokeh, IMHO. Merely the presence of out of focus elements is enough to elicit a response about how lovely they are. Sometimes the comments are referencing a background so insanely outside the depth of field that a catadioptric lens could render it as a smooth wash of color. In either case, it adds to my consternation about an odd compliment.

"And of course there seems to be the new quest for truly awful bokeh. Seeing the success of Meyer Optik's revival of the Trioplan for a substantial sum of money has given me pause more than once. I suppose life would be dull if we all liked the same things, though.

"Anyways, thanks for the re-publishing of an interesting article. I truly enjoyed reading it since I missed it during its first appearance."