So are you of the opinion that advertisements should be honest? So was the Federal Government, once upon a time, when it innocently passed its truth in advertising laws. But truth is fugitive, confusion contagious; tiny prevarications become small fibs, small fibs become big lies, and, gradually, "misleading" becomes normal.

A nagging problem I had as a photo magazine editor was one particular kind of truth in advertising. Advertisers pay for space, and the publisher and the ad sales department want them to pay for space—in fact work very hard to get them to pay for space—and they do not want the raggedy ol' editorial department stepping in and interfering in any way. According to "the business side," as my publisher used to call it, the contents of ads are not any of the editorial side's business. I was encouraged to mind my p's and q's, as well as the other twenty-four letters of the alphabet, and to remain hands-off as far as the contents of ads were concerned. One time, this led to a potentially embarrassing problem.

You would think that advertisers wouldn't lie when it's not even to their advantage. Yet what I found was that it wasn't uncommon for the photographs used in camera or lens ads to have been taken with some other kind of camera or lens than the one being advertised.

A long time ago, an employee of Canon who shall remain unnamed (forever, because I can't remember his name), told me a story about how the young André Agassi was originally recruited to star in Canon Rebel ads. According to him, it seems that Canon execs were getting sick and tired of the fact that the photographers hired by their ad agencies to shoot Canon ads were using Nikon cameras to shoot them with. A prominent Canon-using photographer was proposed for the new Rebel campaign, and that shooter happened to have a great working relationship with Agassi, and a large stock of pictures of Agassi taken with Canon equipment.

Apocryphal? Perhaps. Other sources at Canon have since then categorically denied this story in all its particulars. Despite which, it still seems kinda plausible to me. But then, what do I know?

Robert Monaghan, somewhere on his immense medium format site, reports an example of a Bronica ad that was actually shot with a Hasselblad. Seems the photographer—or more accurately the advertising agency's art director, probably—forgot to hide the telltale frame-edge marks that betrayed the truth, probably because he or she had no idea what the little marks on the frame-edge meant. Oops.

I don't think this is uncommon by any means. According to the ad agencies I talked to and a certain company marketing director who shall also remain unnamed (see above), pictures in ads are "illustrations," and are not meant to be "literal." (Cough.) Besides, if an advertisement is touting a particular lens and has one photograph prominently placed in the ad, it's only implied that the picture was taken with that lens, right? Usually, it’s not explicitly stated. So if you, the viewer/consumer, want to draw the wrong conclusion, well, that’s up to you. (Cough, cough.)

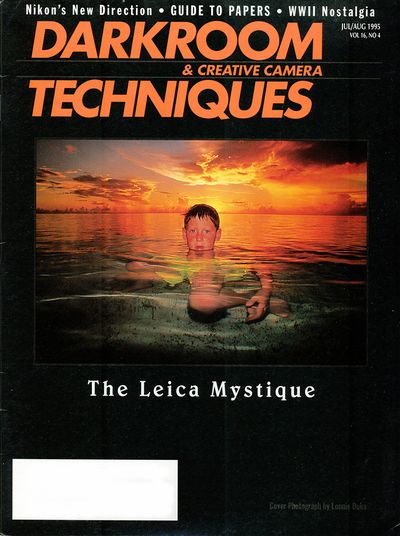

The problem this caused for me happened shortly after the launch of the ill-fated APS film format. An ad for an APS camera began appearing in other magazines that touted the quality of APS pictures. The ads featured a nice, dramatic picture of a swimmer at sunset. Clearly implied (but not explicitly stated!) was that the picture was an example of the kind of quality consumers could expect from the then-new APS format.

The problem was, the picture had been taken with a 35mm Nikon F4s on 35mm film.

How did I know? Because I had run the very same picture on the cover of a magazine two years earlier!

I originally found the picture in a Communication Arts photography special that had been published substantially earlier than our cover had been. So the picture had obviously been made long before APS existed. Our common practice in those days was to contact the cover photographer and ask for the details of how our cover pictures were shot, which we then dutifully recorded in a blurb on the table of contents page.

Fortunately, that particular ad showing our former cover photo had not been submitted to our magazine yet, which helped me when I tried to put my foot down. I merely explained the siuation to the publisher and made it clear that I couldn't publish that ad if it came in. So, did the ad sales person ever have to gently suggest to his contact that that particular ad wouldn't be the best one to submit? I have no idea, and I'm glad I didn’t have to find out. What would have happened if that advertisement had already been submitted, its space bought and paid for? That might not have been so easy. I'm not sure I would have won that battle.

And now for the kicker. (This makes me look bad, but that's never stopped me before.) That cover on which we used the Nikon F4 shot featured the picture right above a blurb that read, "The Leica Mystique."*

Cover photo taken by Lonnie Duka with a 35mm Nikon F4s. The same picture was later used in print advertisements for the APS film format. Cover design by Lynne Anderson (then called Lynne Surma).

False advertising?!? Well, no, I didn't think so, because we clearly stated on the table of contents page that the photographer had used a Nikon to make the picture. A few readers didn't agree with me, however. (And a few of the guys at the Nikon booth at the New York show were tickled pink, which seemed to confirm that I'd made a mistake.) But it looked good. And, if memory serves, it sold well. And hey, it was only an illustration!

Mike

(Thanks to Oren Grad and William Schneider)

*The cover article was written by Carl Weese.

This post is a rerun. It was originally published in "The 37th Frame" in September 2004.

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Mike Stone: "I remember a fabulous week spent scouting locations in the Mojave desert and then assisting on the shoot for a Canon ad back in the early 'nineties. Dramatic B&W shots. All shot on a Hasselblad SWC."

Damien: "Target rich, and depressing, environment, really. Hair product companies use models with hair extensions to infer this is what their product does. Virtually all magazine covers are Photoshopped. All this and so much more is fair game, and legal, where any sort of nonsense can be shouted from the heavens, as long as a disclaimer for all the blatant falsehoods is whispered somewhere also.

"Often no disclaimers are required, the Photoshopped magazine covers being a prime example, which should all be regulated, and carry warnings if excessively Photoshopped. There is a middle ground between false and truthful advertising however, and I would label it 'misleading advertising.' Your magazine cover is a prime example of that. Of course, I see nothing changing, aside from all of us mistrusting advertising even more as time goes on. If the advertising industry had any sense, they would regulate this sort of stuff themselves, as they are letting their product be eroded and destroyed slowly from within."

Mark Hobson: "I remember well the day I walked—though some would say 'paraded'—through the Kodak corporate lobby on my way to deliver the finished results of an ad shoot.

"This was something I did on a regular basis. The ad assignment was, uncharacteristically, for B&W pictures—color was the usual norm. No big deal. I was very proficient in B&W and chosen for the assignment based on that expertise.

"However...the prints in my sample portfolio were made using my B&W standard operating procedure of Kodak B&W film printed on an Ifford B&W fiber-based paper. Consequently, that's the manner in which the assignment was completed. On hindsight, doing so was a brain cramp of major proportions. I should have found and used a suitable B&W Kodak paper for the work.

"But not doing so was the least of my sins. Walking (parading?) through the Kodak lobby and hallways with a 16x20 Iford paper box—it's amazing how a white box with black typography stands out in a sea of yellow boxes with red typography—was indeed the Mother of All Brain Cramps.

"Fortunately, after reprinting the pictures on Kodak paper, I remained in good standing with Kodak and its agency."