I've thought a lot over the years about why certain things seem "reasonable" to humans, musing on some of the possible reasons why. War, for instance, seems not only sensible but inevitable, whereas it has always seemed outlandish and appalling to me, the furthest thing from "reasonable." My small consolation is that, in early modern Europe especially, duelling seemed as utterly unavoidable as war seems to us still; and at various times and places the carnage was very considerable. It may return, but society has for the moment at least learned to dispense with duelling, for the most part. I'm sure such a development would have seemed impossible—incredible—to any conventional upper class nobleman in 17th-century France. My belief—all right, my hope—is that someday the same fate will befall the custom and convention of human warfare.

Just yesterday we touched on this—this idea of seeming "reasonableness." It simply doesn't seem reasonable to some people that a train can sneak up on you when you're on the tracks. Too much evidence suggests otherwise. "Counterintuitive," we call that. A phrase I've always thought shortchanges real intuition. So much of human activity is determined by such superficial assumptions.

The reason I introduce the topic this way is that it seems intuitively reasonable to some of us that fame, success and money would necessarily supply whatever is wanting in our psyches or salve whatever pain is in our souls, and arm us well in our personal struggles; the evidence doesn't support that either, at all, but somehow we keep being surprised that it isn't so.

I mourn the loss of the great actor Philip Seymour Hoffman. Demotic culture at the moment revolves in large part around "celebrities," many of whom act in order to undergird their notoriety, but real actors are still relatively rare and of course geniuses of the craft rare always. He was an extraordinary actor, fearless. Hoffman at 46 had a number of great performances to his credit and many great performances still to give, and his death is a deep loss to culture and art. His death is as senseless and tragic as that of a young person cut down in traffic. His body of work has been brought to a skidding halt.

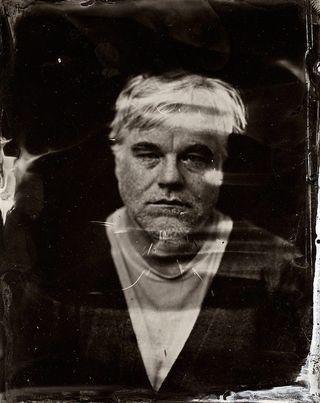

Take a contemplative look at one of the most extraordinary photographs I've seen in a long time. Just a few weeks ago, many actors and actresses posed for tintype (wet collodion) portraits at The Collective and Gibson Lounge, "Powered by CEG" whatever that means, during the 2014 Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. The photograph of Hoffman is in the middle of the second to last row at this link, and the context is interesting. It's credited to Victoria Will. The picture cuts to the resignation of a human being overwhelmed by addiction, such that it's almost more a portrait of that than it is a portrait of the person. I interpret it as the look of someone who thought he had won his fight against the wolf of addiction but who suddenly finds himself right back in the battle again, as deeply as ever. That's just supposition, supplied by my imagination and a few cues from news stories. But his struggle is right there before our eyes—right there in his eyes. Celebrity and success utterly impotent as defensive weapons against the great weight of that despair.

As great a "psychological portrait" as I've ever seen, but one I very much wish we didn't have.

Mike

(Thanks to Arthur Elkon and Gordon Lewis)

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

CharlieH (partial comment): "Or he was just acting. I say that because most of the actors who sat seem to express a similar melancholy. Its much harder to smile for the camera then to look mean or stoic, or just sad."

Steve Ducharme: "I've spent far more time around addicted people than any reasonable human being ever should and that haunted look is not unfamiliar to me. You are not reading too much into the photograph. In fact the process is almost like a filter exposing the anguish and resignation within. Sad and moving."

Paul De Zan: "Philip Seymour Hoffman's death is highly instructive. He wasn't a publicity-seeking diva. He did not flaunt his wealth. He did not do 'bling.' He worked very hard. He had kids he loved. His addiction did not play out in the tabloid media. He didn't experience a long, sad decline. And the drugs killed him anyway. He probably had no more idea he would end up dead with a needle in his arm than a person shot at random by a mad sniper. No idea at all. Bloody hell."