[Ed. Note: This post was modified after many of the first comments had come in.]

I found an old print the other day. I was playing fetch with Lulu (in the house—she hates snow because it gets in her pads and makes her miserable) and a tennis ball rolled under the...well, I don't know what the piece of furniture is called—three drawers below, three shelves up top? It must have a name, but I don't know it. An old Victorian one that originally came out of my great-grandmother's house.

When I went to fish the tennis ball out for her, I found a surprising little nest of mess under the whatever-it's-called. The toxic carpet in my house spontaneously generates clumps of dust, and a number of items were hiding there amidst the dust-bunnies, including not just the one but three tennis balls. And one of the many things I found was an old print, curled and covered with dust.

The art photographer John Gossage, who taught a graduate program in photography at the University of Maryland, once came to make a presentation to my class at the Corcoran School, and one of his pieces of advice was to never throw old work away. He was lecturing on process, and talking about how to use old work to direct newer work, and he thought old work provided clues. "Don't throw it away," he said, "keep it. Just throw it in an old box somewhere." With my natural packratty tendencies, I don't need much encouragement. My house is full of old prints.

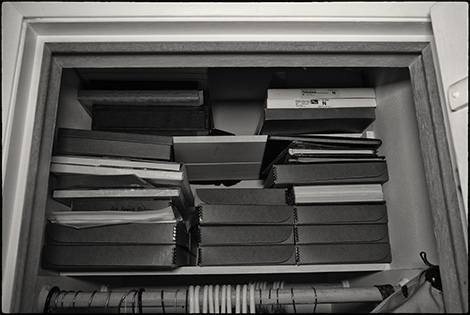

One of three temperature-controlled storage vaults at sprawling TOP World Headquarters, for "prints," which as you know is another name for unconnected images. There is also a fair number of prints lying about,

One of three temperature-controlled storage vaults at sprawling TOP World Headquarters, for "prints," which as you know is another name for unconnected images. There is also a fair number of prints lying about,

including, um, under furniture.

The print I found was from my first year of teaching, which I think was 1985–6. I had let my classes take pictures of each other with my 4x5 and Polaroid film. I'm sure I kept the stack of Polaroids, and they're doubtless still around here somewhere.

Very few kids get to be what they wanted to be when they're little. That's a good thing, because otherwise most of the male population of my generation would consist exclusively of firemen, policemen, and astronauts. I actually remember a big group argument in first grade over which of these three aspirational professions was best. (Each kid was expected to choose sides. I honestly think I tried to argue that we needed all three, to the scorn of my small friends. Pick a side and fight!) And the female population in my demographic would definitely have a surfeit of ballet dancers.

I always wanted to be a teacher when I was little. I knew this from the very first time I sat in a regular classroom in front of a teacher. Sized up the situation and just knew it was for me. I became really conscious of it in third grade, because I realized I was habitually critiquing my poor teacher, Mrs. Enz, as she went along, learning from her not only what she was teaching, but how to teach; that is, when she did something good I'd think I've gotta remember that. And when she did something not so good....

I had to get a retainer cemented into my mouth in third grade to hold my tongue back, because supposedly my tongue was pushing my front teeth forward and was going to make me buck-toothed. I essentially had to re-learn to speak. When I talked I sounded like someone had grabbed my tongue and wouldn't let go. My mother wrote a note for me asking the teacher to have mercy on me and not call on me for a week or two while I got used to it, but Mrs. Enz was having none of that. She called on me more than she usually did during those days, I suppose because she didn't approve of special treatment, or because she thought I needed practice. So she would call on me and patiently wait while I made noises like a strangled cat, blushing bright red in embarrassment, while all my friends giggled at me and mocked me. I remember thinking, hotly, I am NEVER going to do this to a kid once I'm a teacher.

Unlike most people, I achieved my childhood ambition. In my third and last year in photography school we had to do internships, and I landed an internship as an assistant teacher to a photographer named John McIntosh at Northern Virginia Community College. NVCC was actually an extensive photography program, very well funded, with a number of full-time professors and excellent facilites and equipment—it was where all the photography instruction for the entire Virginia community college system was concentrated. They liked me well enough that they asked me to return the next year to teach a Photo 101-102-103 sequence in the Continuing Education Department.

I was mystified to learn that Instructors were required to fill their own courses. Evidently you were supposed to go out and drum up enough business for your class to fill it, by yourself. If enough people signed up, the class would run, and you had a job; if only a handful signed up, the class would be cancelled and you'd be out of luck. With my poor memory for numbers, I can't recall now what the break-even point was. Luckily, my classes filled to the brim without my having to do anything. Which was a good thing, because I didn't have the slightest idea how to go about lassoing enough students if the task had come down to me.

During that year, the Director of the program, David Allison, called me to his office. He told me there was a full-time position as a photography professor opening up, and they wanted me to apply for it. They wanted me to go through the entire application and interview process. He gave me a list of all the things I'd need—a resumé, a portfolio, a jacket and tie, and so on.

Naturally, I thought this meant they wanted to hire me.

"Oh, no," David said. "You're not going to get the job. You don't have enough experience."

Huh?

It turned out he wanted me to apply for the job so I'd be ready to apply for other jobs. David told me they thought I was a natural teacher and they really thought I should make teaching my career, and they wanted to help me on my way. It was one of those compliments that stick up above the waves, and I've never forgotten his kindness to me.

I did go through the entire process, as David had set it out for me, and it paid off right away. NVCC hired a woman who had been teaching at a local prep school...in August. This left the prep school scrambling to replace her at the last minute. Classified ads resulted in lots of applications but not very good-quality ones. So they asked the outgoing teacher if she could help find her own replacement, and she in turn asked her new employer—David Allison—if they could suggest anybody. Fait accompli.

I taught at that prep school for three years, and loved it. Looking back on it from the perspective of advancing middle age, I have only been happy a few times in my life, and those three years were the happiest. Or at least it was the longest sustained such period. (I have not lived a happy life. I really should write my autobiography one day; it would be very entertaining if I were able to be sufficiently honest.) I loved the work, as I always knew I would.

Unfortunately, human beings are predisposed to what my son calls "drama"—interpersonal turmoil. My son, who is more socially adept than I am and much smarter about such things, once quit a good job as a waiter at an Italian restaurant after only two weeks. When I asked him why, Zander, in his laconic, man-of-few-words way, said, "Too much drama. None of it involved me, but it was only a matter of time." Smart kid.

I thought my basic goodness was sufficient armor at that long-ago job, but it was not. A popular young male teacher at a school for girls—and full of female teachers, at least one of them young and elegant and married—is a recipe for drama. And it was only a matter of time.

But still, it was a great job while it lasted. Now, teachers aren't supposed to show favoritism (learned that from Mrs. Memmel, fifth grade), but they're human, and they can't help having favorites. The old Polaroid I found was a picture of two kids, best friends, probably before I knew them well, who later became two of my most favorite students. Just absolutely delightful kids, of the sort teachers privately and quietly consider it an honor to know. (I'm sure you teachers out there know just what I mean.)

Seeing their faces, unexpectedly, in a picture I barely remembered, really took me back. After I carefully wiped the dust off that old print it transported me into a sort of happy reverie of memory. It released a flood of nostalgia that I indulged myself in for hours as I went about my household chores. Sentimental...yeah, sure. So sue me. I am way too sentimental about my long-ago sojourn into teaching; I know that. But if I could have, I would have grown old in that job. And I'm certain I would have enjoyed every year more than the last. I paid dearly and suffered long for some unexceptional youthful indiscretions. There are times when I could convince myself that I have missed teaching every day of my life. That is not strictly accurate, because in truth I don't think of it every day, even every week. But I have always felt like an unhappy exile. I am very aware, very aware, to this very day, that I missed my calling in life—not the happiest of realizations for a man to have heavy on his back in middle age.

So here we come to the point of this whole reminiscence: what are the chances you're ever going to find an old digital file under a piece of old furniture?

All right, calm down. I'm not slamming digital.

But that print was ephemera the day it was made. The kids were just trying the camera, playing with the materials. The only reason they used each other for subjects is that that's what was handiest. The prints themselves were detritus. Never important. If not for John Gossage's advice, I might have tossed them right then and there (I probably didn't because Polaroid was so expensive and it seemed like a waste of money to just throw them away). If they had been digital, we'd have erased that print I found right when it was made, or a day or two later. Even if we hadn't, what are the chances I could come across it adventitiously in twenty-seven years' time?

I don't want to belabor the point, but I also don't want to let this get away without making sure I've made the point. There are obviously lots of advantages to digital creation, digital delectation, and even digital storage. (I'm currently looking for a picture I wanted to use to illustrate this post, and I'm still looking. All those prints in the top picture are not organized, and the only way to find anything is to go through everything.) But we shouldn't let that blind us to the often whimsical and surprising ways that physical prints survive sometimes, and the emotional wallop they can pack when they surface adventitiously again—or when the meaning of otherwise nondescript pictures shifts tectonically with time. Here is a lovely and moving example of the latter, written by Michael J. Perini. It's not either or, it's both, and they're different.

In other words, society needs policemen and firemen and astronauts. Plus a lot of other things besides. :-)

I don't know if you've noticed this, but it's something I'm very aware of: in the photography community, we're actually kinda like a bunch of teenagers when it comes to choosing up sides. It's "team this" or "team that." You've got to be on Team Canon or Team Nikon. You've got to be on Team film or Team digital. Team color or Team black-and-white. Team IQ or Team Lomography. Team darkroom or Team computer (please, somebody stop me). The squabbling almost always seems to devolve to that—or, at least, lots of that clogs up the discussions.

Bah, I say. I always want to advocate for balance...for looking at all things, and both sides of everything. How else can you really understand the ramifications of all the changes that are taking place? You can't just look at how things are getting better. Or rather you can, but that doesn't mean you can't be mindful of things that are getting lost.

I'm most aware of this when we talk about darkroom work. Instantly, everybody assumes we want to know what Team they're on (even here at TOP, where the discussions are often on a higher plane than they are at some other stops out on the Wild Wild Web). Why? Who cares? It's not a contest. Darkroom is dead, a shadow of a niche of a niche. Even in its heyday, the biggest home darkroom magazine had a circulation of 105,000—not exactly Better Homes and Gardens level*. It's almost impossible to talk about process, craft, and the fundamental differences of approach and strategy that the differences highlight—the spectre of choosing sides is always looming above us and casting its shadow. I'd rather look at what we've gained, and also what we've lost. It's not either-or. Balance, balance.

How can you appreciate what you've lost if you can't look at it?

Mike

*Circulation 7,624,505 in the first half of 2013.

"Open Mike" is The Rambler, The Spectator, and The Tatler of TOP. Published on some Sundays. Even when there's football, and I hope you're appreciating that.

Original contents copyright 2014 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

John Camp: "My mother died on the last day of 2013, at age 93. She'd had a good life, and was a good mother; and I was her oldest son. A few years ago, as she was cleaning out her house to move into an assisted-living apartment, she gave me a shoe box full of old family photos. Most of the photos were the kind of thing that you put back under the bed and mostly forget about; but one of them, a snapshot in black and white, and not more than about three inches by two, shows her as a 25-year-old, hold me as an infant.

"The thing is, not only is a fine memory photo, but it's one of those random masterpieces that accidentally get taken from time to time: pretty woman, by herself, holding a swaddled child madonna-like. The composition and printing are excellent, and tonal variety perfect. My wife wife put it in a small silver frame, and I will treasure it forever."

rnewman (partial comment): "So why not go back to teaching as a part time job? I expect you could easily get an adjunct professorship at one of your local colleges, either in a certificate/degree program or in a non-degree program. I would be a change of pace and expose you to new/different approaches and issues which you might otherwise not be in contact with."

Mike replies: I came very close to switching to a teaching job when I was at the magazine. A contributor was a professor at Ithaca College and there was an opening in their photography program. It went quite far along—I believe I even had a plane ticket (reservation?) for the interview—until one day she called and said, "By the way, there's something for some reason we don't know—where did you get your master's again?" I told her I didn't have an MFA, only a BFA. There was a pause at the other end of the line, and then she went, "Ohhhh..." and I knew that was that.

It's odd that I don't have a master's when I could probably teach in a master's program by now, at least in studio art (that is, not scholarship). I and A.D. Coleman (one of the leading American photography critics of the last half century), of whom the same thing could even more easily be said (except that he could teach scholarship, and probably not studio), once somewhat idly concocted a scheme whereby he would be my advisor and I would be his advisor, and we would work under the supervision of a University department that would go along with the plan. I got as far as getting a thumbs up on the idea from the late Bill Jay when he was at Arizona. But you know how it is; life gets in the way. It's more difficult to do things in life out of sequence.

Lois Elling (partial comment): "May I remind you that you are still teaching; you teach your readers every day."

Mike replies: That's the idea, anyway! Although it's reciprocal—my readers are my teachers, too. Thanks, Lois.

John Hufnagel: "In my part of Pennsylvania, that piece of furniture is called a 'hutch' or a 'hutch cabinet.'"

psu: "This 'shoebox' issue is probably the thing that worries me most about digital pictures. The issue is not so much that I think pictures will get deleted. There is no real reason to delete them these days because storage is practically infinite. The more worrisome issue is that when you leave bits alone in the dark and don't look at them once in a while they rot away, and there is not as yet any real solution to this issue. The only viable backup strategy for the long term is to periodically make copies of everything. But this requires that you have someone around with an interest in making these copies. When that person is no longer around, the pictures will sit in the dark by themselves and just rot away. This probably isn't an issue for 'important' pictures. But one wonders how many other pictures will be lost that would not have been in the past because they could just sit in a box maybe be OK. I wonder what the relative survivability of digital vs. analog shoeboxes is."

Mike replies: It's a very valid question. Obviously the attrition of printed images is massive as well, and it's inexorable too—I once read a fascinating essay by an expert on collectibles who claimed that physical items will be gradually lost even despite efforts to preserve them, something that can be observed even in the small, gradual losses among the world's most valued art objects. Although value is one thing that improves survivability. Among much less precious items, there is a fairly strong effective randomness or unpredictability about what does survive, and how.

Marco Sabatini: "Two citations from ancient Greece: Socrates: I cannot teach anybody anything, I can only make them think. Theophrastus: Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel."