This week's column by Ctein

I know I've been neglecting my off-topic

obligations (if they can be called such). Just too much good photographica to write about.

Finally, here's another one (and there'll be a

second part in two weeks). For thems of you whats

hates these, come back next week for more of my

photobabble.

Miles O'Brien, PBS Newshour science correspondent, interviews an expert panel on the history of the Johnson Spaceflight Center and NASA.

Miles O'Brien, PBS Newshour science correspondent, interviews an expert panel on the history of the Johnson Spaceflight Center and NASA.

Last September, Houston was the site of the first

"private" 100 Year Starship (100YSS) conference.

The previous year's 100 Year Starship conference

was a DARPA-initiated government conference. You

can read my report on it.

This year's conference was the first hosted by

the 100YSS Foundation, established with a DARPA

grant of $500,000 after last year's confab. The

reason for the quote marks around "private" is

that anybody could attend; you merely had to pay

the conference fee.

As I explained previously, DARPA doesn't build

stuff. They spark interesting and innovative

endeavors and then they throw a little money at

private entities to kickstart the thing. Their

interests are national security and defense,

staying ahead of the rest of the world's

technology curve. Forty-something years ago, they

envisioned it might be useful for the Defense

Department to have a robust and distributed

communications network in case war broke out. The

result was something called ARPANET. Ever heard

of it?*

The 100 Year Starship is considerably more

ambitious. Its goal is, over the next century, to

either build and launch a starship or to

establish the technological, industrial,

managerial and economic base that would be

capable of doing so. DARPA doesn't especially

want or need a starship. The myriad

instrumentalities and technologies required to

build such an amazing endeavor, though, would

transform U.S. science, production, and

manufacturing even more radically than the Moon

Race did.

Unfortunately, the path to the stars is much

longer and much less clearly defined than that to

the Moon. I truly cannot speak for all 250

attendees, a substantial fraction of whom were at the first year's DARPA conference, but my sense of it

is that the consensus feels similarly: we all

hope this venture will succeed, and we all expect

this first attempt won't. There are too many ways

it can go wrong, too many mistakes that can be

made. It would require great luck for none of

them to prove fatal to the enterprise. But, one

has to start somewhere, and the objective is to

learn enough so that if the 100YSS fails to

achieve its goal, the next attempt will fare

better.

Which still leaves the problem, how do you do

this? More specifically, at this early stage, how

do you build an organization that could attempt

to do this?

I'm sure that's the problem DARPA faced when they

looked over the request-for-funding proposals

from last year's conference. I heard that there

were close to three dozen submissions. Among the

half-dozen top ones, I doubt there was a single

one that wasn't worthy of funding. They ranged

from "let's start cutting metal tomorrow" (only a

modest exaggeration) to "the problems are still

so ill-defined that we shouldn't jump into

anything."

DARPA decided to go the latter route and awarded

the grant to the proposal from Dr. Mae Jemison

(see my previous column) and The Jemison Group.

In six months they managed to go from getting the

grant to pulling off a major conference. I know a

little something about throwing conferences. When

you're running that fast there will be problems,

and there were a few, but it gets a solid B+. These

people are very good at moving fast. Not so

incidentally, the 2013 conference will be held in

Houston this September. I plan to be

there.

What did this first conference accomplish? Well,

now, that's an interesting question.

Content-wise, very little. That has some people

frustrated (especially the cut-metal set). My

take on it is that this event was mostly about

process—setting up the sociological constraints

and boundary conditions that would facilitate

getting to concrete answers down the road. (Most

interestingly, I realized that this conference

bore substantial similarities to a project I was

involved in over 40 years ago. More on that next

time.)

I'm not privy to the inner workings of the 100YSS

Foundation or their agenda. Three process goals,

though, were clear to me. The first was to create

an intellectual "big tent." When you aren't sure

what the right approach to a problem is, you

don't want to be rejecting possibilities and

talents out of hand. You never know what you'll

need later. You explore as many avenues as

possible, in parallel, and try to avoid tossing

any out prematurely, just because one seems most

promising at the moment.

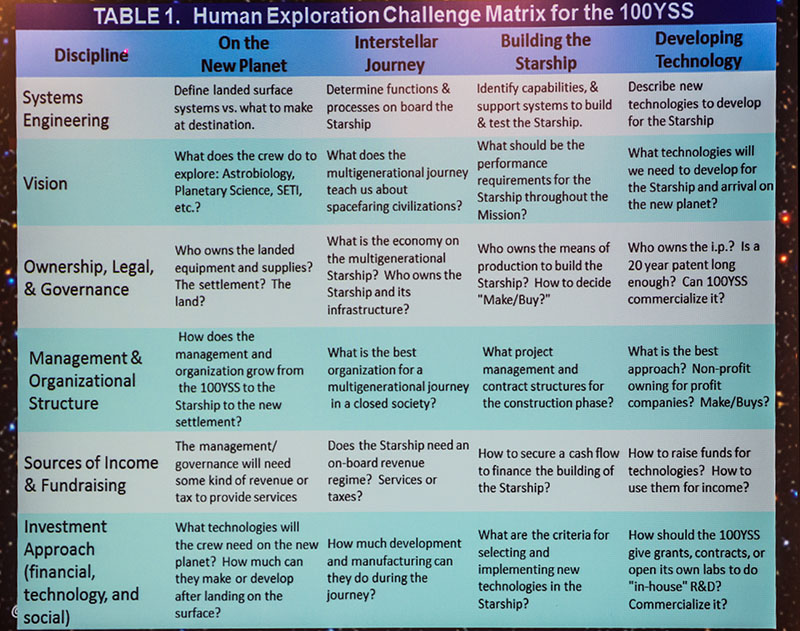

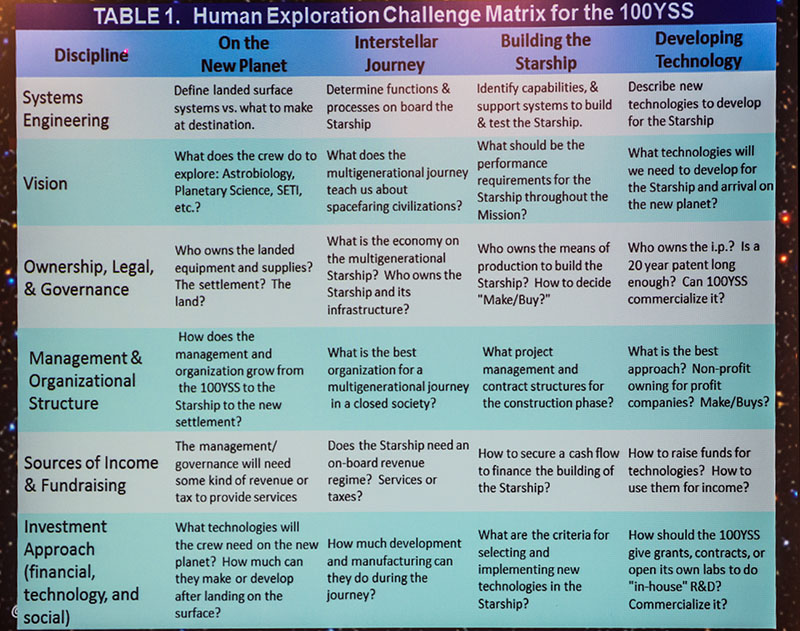

So many questions, so few answers. One

speaker's take on just some of the matters that

will need to be addressed to make the 100YSS

project a success.

So many questions, so few answers. One

speaker's take on just some of the matters that

will need to be addressed to make the 100YSS

project a success.

Sounds good in principle. In practice it can be

dicey. For one thing, most people need focus to

accomplish anything. If the immediate problems

and goals seem impossibly diffuse, it's difficult

to get anywhere. It can also lead to mission

creep, where the goal perpetually mutates in ways

that have people spinning their wheels, or leads

them down a garden path they never meant to

follow.

It's also frustrating to the people who have a

clear idea in mind of how the problem should be

solved (whether or not they have the best

answer). They want to get moving on a solution

and tend to be impatient waiting for the Big Plan

to jell. Entirely understandable, unfortunately.

You have to figure out ways to keep those people

happy so they don't leave in frustration.

In fact, several autonomous subgroups

spontaneously appeared from within the conference

attendees—like-minded people who are trying to

pursue their more immediate goals without having

to wait for the entire operation to arrive at

consensus. I have this suspicion that the

Foundation expected that to happen. As I said, a

big tent.

You're also at risk of infiltration by nutters

and crackpots, and you want to make sure they

can't hijack the agenda or appear to be

representative of the group. We had just a couple

of those. I would say that most of the people at

the conference, though, were a lot like me:

smart, educated, with a hard head and a practical

mind, and open to new ideas...but with large

bullshit filters. It's harder to hijack a group

like that. Still, it's a possibility that I'm

sure the Foundation is wrestling with, because

circumstances can change, and dealing with this

potential problem is a complicated process issue.

None of which is to say that the "big tent" is

the wrong approach. Personally, I think it's the

only one that has a chance of working at the

present time. That doesn't mean it isn't fraught

with peril. We'll see how well it works out.

The second goal? I'll get to that in the second

part of this column, in two weeks. A hint—when

I said the people were a lot like me? In some

very important ways, I lied. Ah, the anticipation....

©2013 by Ctein, all rights reserved

*Satire alert

Original contents copyright 2013 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

TOP links

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Hugh Crawford: "The Ownership, Legal, and Governance part is the most interesting. It sure won't be capitalism as we know it."

John Camp: "I find the concept fascinating, as much for the management problems as for the actual development of a starship. Cutting metal at this point seems absurd, when you don't even know who or what would go to another star. To send off a crippled mission in ten years that wouldn't even be able to report back before it was obsolete seems foolish. (For example, you have to decide exactly what you'd want such a mission to return in the way of results—but the earth-orbit astronomical telescopes are now returning such a wealth of new information that it would seem to me most profitable to try to expand their capabilities, and in x number of years you might be able to find out much of the information that you'd get from an actual probe. I mean, do we really want to spend trillions to send a starship out to a place if it reports back in two hundred years that the target planet is another Mars? In other words, close, but no cigar?)

"It's a great thought problem, though, and would take excellent management just to catalog the relevant thoughts.

"But—$500,000 is trivial. In fact, it's so trivial, that I suspect most of it will be wasted. $500,000 per year might get something done, but not much—that might buy you a three or four-person staff. What we need to do is get rich SF writers, and there are at least a couple of dozen of those, to kick in a tax-deductible 5% of their income to a starship fund...."