Fraudulent misrepresentation, negligent misrepresentation, unjust enrichment, and promissory estoppel. Those are the bases upon which collector Jonathan Sobel sued photographer William Eggleston in April 2012.

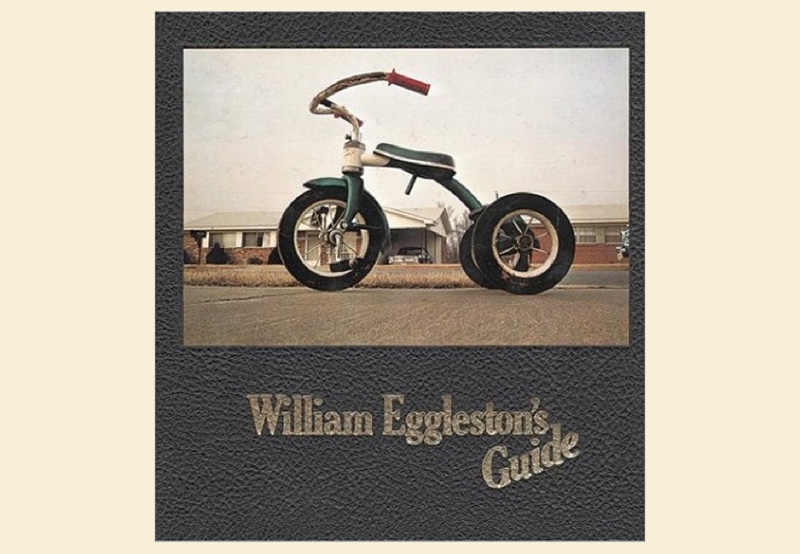

Sobel had paid a reported $250,000 for a large (~17" wide) dye transfer print of "Memphis (Tricycle)," the famous picture that graces the cover of William Eggleston's Guide , one of the landmark American photography books of the second half of the 20th century and a seminal work of color photography. Sobel's print was supposed to be a "limited edition." When Eggleston sold a copy of the same picture—printed digitally, and considerably larger—for $578,500 at Christie's last March, Sobel was not pleased. He sued. Seems understandable.

, one of the landmark American photography books of the second half of the 20th century and a seminal work of color photography. Sobel's print was supposed to be a "limited edition." When Eggleston sold a copy of the same picture—printed digitally, and considerably larger—for $578,500 at Christie's last March, Sobel was not pleased. He sued. Seems understandable.

Judge Deborah Batts of the U.S. District Court in the Southern District of New York, however, dismissed the suit last Thursday, writes Julia Halperin at ArtInfo. Seems the Judge agreed with Eggleston, whose representatives said the larger inkjet prints in the Christie's sale are a new expression of the work.

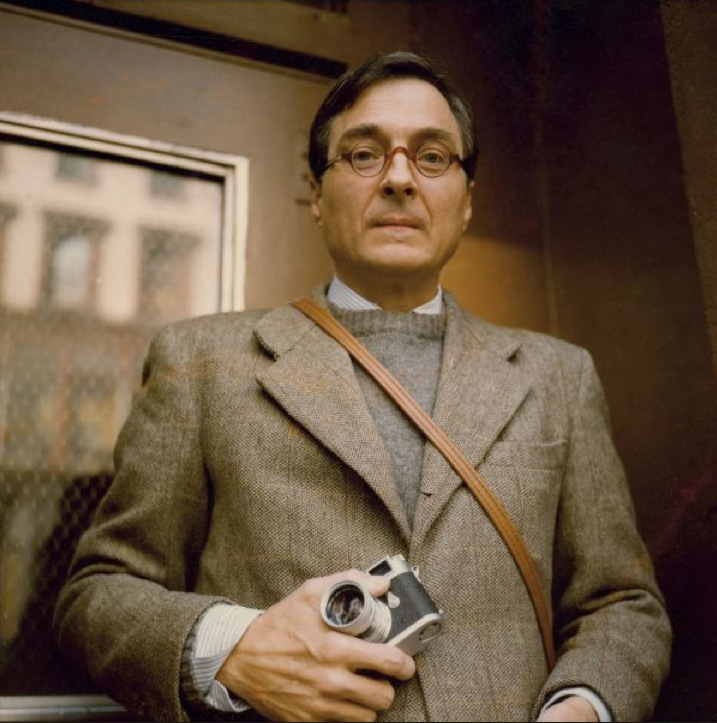

Bill Eggleston*. Photo by Maude Schuyler Clay

Bill Eggleston*. Photo by Maude Schuyler Clay

That also seems reasonable, actually. Strictly, an "edition" is a multiple printing of a photograph at one time and using one method. "Limited edition" basically means that you're printing only so many and that's that. Saying it's a limited edition is just a formalization of that reality—you might give each print a number, announce the total number, and mark the prints with some sort of identifier that makes it easier for people to tell they're from that edition. This all comes from printmaking, where many techniques technically limit the number of good copies that can be made.

The art community has long frowned on artists confusing the issue, but at the same time has long been lenient about allowing other editions—as long as they're distinct from the limited one and not likely to be confused or conflated with it.

In that sense the Judge has gone along with standard practice (insofar as there is such a thing) in this case.

Sobel, who owns 190 Egglestons, still disagrees.

He's wrong about one thing, though—he claimed that the sale of the newer inkjet prints diluted the value of his holdings. Unlikely, in our humble opinion.

Mike

(Thanks to John S Krill)

*Anyone know who took this? I spent some time searching, but have not been able to identify the photographer.

UPDATE from Hugh Crawford: "Maudie Schuyler Clay took it way back when.

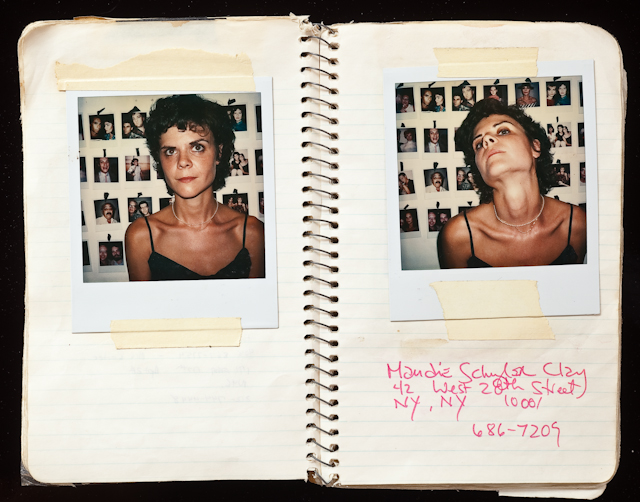

"Maudie in 1979—Polaroid diptych—edition of one."

Mike replies: Thanks Hugh (and the others who replied and correctly identified Maude). I did try to email her, but have gotten no reply thus far.

She's quoted in this article talking about the portrait. (Thanks to Rodger Dicks for the latter.)

Original contents copyright 2013 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

Please use TOP links

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

Alan: "Working in an art gallery that sells limited edition prints, it's a

familiar problem. Whilst nominally legal to release new editions of

pieces at a later date in different sizes or formats, it always feels a

little dishonest. Similarly, many of my clients who bought a 'rare, sold

out piece' often experience upset when they see it on the wall a few

years later. For my money, make as many editions as one pleases, but I

feel they should all be acknowledged on the provenance of every single

piece from every edition (unless of course the piece is only ever an open

edition and sold as such)."

Chaitanya Patel: "For the record, I am a lawyer, albeit not in New York, and I think that legally (and in my view morally) the decision was the right one because the fact that one edition is limited, does not preclude other editions being made from the same negative.

"However, some of the responses to this post have been not about the law, but about what people feel in their bones to be right and so I'm going to chip in with what I feel instinctively about this. I haven't spent a great deal of time thinking this through, so I would appreciate robust criticism of my position if anyone strongly disagrees.

"I think there's something inherently wrong about valuing a piece of art higher because fewer other people get to see it, or get to see it in the same form. I think as a collector, if you enjoy something and buy it on that basis, you ought to be glad that others will be able to enjoy it as you did, or in a slightly different format.

"If you don't, my view is that your position is selfish and narcissistic and is built upon a foundation of denying to others a pleasure that costs you nothing.

"If your response to this is to say that the collectors' pleasure is not merely one of aesthetic appreciation, but also that he made a financial investment based on the promise of limited supply, then all I can say is fine, but he or she does that within the legal system governing these contracts, and can't complain if they haven't fully understood for what that allows in terms of future editions.

"I also think that artists shouldn't issue limited editions, but somehow I'm less annoyed at them for doing that than I am at collectors for getting annoyed when it doesn't mean very much."

Mark Roberts: "I think Sobel's goal is...exactly what he's achieving now: Great

awareness of the existence of a relatively small number Eggleston prints

in a now-reproducible medium (dye transfer)...and a subsequent

increase in their value.

Production of new, expensive Eggleston prints in inkjet media will do

nothing but increase the cachet (and price) of the old dye transfer

prints. Whatever Sobel is spending on this lawsuit is an investment that

will pay of handsomely should he ever sell his prints. And I think he knows

this perfectly well."