I think the faith behind art photography is the belief that if one single sentient operator decides a) what to take pictures of and how, and then decides b) which of the results to print or publish or otherwise make available to others, and what format and order to present them in, that this double selection process will let something of that individual's unique outlook, or concerns, or way of seeing, or taste shine through into the picture or pictures, either singly or as part of a group—or even more durably, as a consistent, persistent style. If the effort is successful, the pictures will say something about the unique genius of the person as well as what the picture shows.

Like any such definition, that one's perched at the target end of a machine-gun range, ready to be shot full of holes. For one thing, for 90% or more of the vast mass of the digital tsunami pictures flooding the Web, armored with copyright notices and emblazoned with stern warning of all rights reserved!, authorship matters not a whit, not a whisper. There isn't a trace of distinction in any of them, much less any personality, much less any soul. They might as well have been taken by a robot with an auto-interval camera on top. The Web is rife with "clear pictures of fuzzy concepts."

And many different photographers have had their own ways of refining or adapting the basic art-photography idea. Many photographers don't do their own editing. Many (especially now) don't do any editing. To some, the craft is paramount; for others, the craft is delegated. Some people shoot a lot, some a little; some like found scenes, others like to control everything in front of the camera. Some people like funky equipment and sloppy technique, or accidents, or the telltales of photographic "errors" such as motion blur or odd cropping, and others are fastidious or even fanatical about every detail of "image quality" (a loaded term if ever there was one).

When any of the competing parameters get too far out of balance, it becomes a distortion. The various distortions are sometimes even based on fashions or trends. One trend I see now among photo enthusiasts and hobbyists is for people to be very demanding about the equipment they use but not at all demanding about what they do with it.

But one thing that most photographers seem to take as a given, a basic foundational principle, is that for a photograph to "be" someone's picture, he or she had to push the shutter release. That much, everyone seems to take for granted.

Is that really true, though?

It was certainly truer the earlier you go, because the general trend as you go backwards in time was for every exposure to be more precious, both in terms of resources (expense) and the work that was required to support it. If you had to clean a holder, load a sheet of film in the dark, and then develop the exposed sheet by hand, yourself, wait till it dried, then expose and process a contact proof, then you were hardly likely to make the exposure thoughtlessly. You were very careful with how you committed those resources of money, time, and effort. That was only amplified if your picture was made on a mammoth glass plate you had to coat with emulsion just before the exposure, and the whole shebang was transported to the picturetaking location on the back of a burro.

Now, we're fast approaching the time when—far past mere 35mm film and motor drives—it will be easy to shoot actual video (handheld, in any light, and at virtually no cost per frame once you own the supporting devides) and then select a frame from it to use as a single still image or make into a single print. It's a very different mindset.

To approximate the different mindsets involved, I used to require advanced students to shoot six or ten rolls of film in a few hours. Usually, that was far more than they were used to shooting, and in many cases it was more than they had ever shot at one go. Then, as a parallel or complimentary exercise, I'd have then go into the darkroom, cut a shot strip of unexposed 35mm film, and lay it in the film gate of their camera, close the camera on it, then go out and shoot that single exposure, taking at least an hour to do it. The extremes led to some interesting insights—with more film to expose you almost had to free yourself up, get looser, and experiment, and you could take more shots of any subject you encounter. And it encourages risk-taking. With one shot only, on the other hand, you have to reject almost everything you see through the viewfinder, and, even if you find something you really like the look of, two things are likely to happen: you'll be really careful about your camera settings and your standpoint, and you'll be balancing in your mind the possibility that you might see something better later.

Nowadays, in the digital era, the first part of this exercise is commonplace—there's no direct cost to clicking the shutter, and your card will hold hundreds or even thousands of shots without even requiring the simple, quick task of changing cards—but the second is foreign to us, actually almost impossible to simulate. But it's closer to the way a great many photographers worked, historically speaking. Walker Evans used to come back from a hard day's work with six sheets of exposed film. The discipline of having limited exposures with a lot of effort and expense attached to each one was good for the mind; it made photographers really think about what they were doing, and honed their eye for just the right moment, just the right framing, and so forth...as well as their sense of what was really worth a picture and what wasn't.

But back to the subject. I can think of a number of instances where photographers didn't push the shutter button themselves. A number of "Mathew Brady" photographs of the American Civil War weren't taken by Brady, but by "camera operators" in his employ. Being the de facto editorial director and the studio owner were enough, in those early days, to tag the pictures as "his." (Subsequent historians have been more discriminating in the distinctions—i.e., they want to know who the camera operator was.) I recall reading a story about a famous studio advertising photographer who would have his assistants set up a shot, and then he would come in and fine-tune the shot with many Polaroid proofs. Then, when everything was perfect, he'd leave the room and let the assistants expose the actual film for the picture—a trivial detail not worth his time. Wildlife photographers of course set "traps" with cameras set up with various triggers to be tripped by wildlife; they themselves aren't actually present when the picture is made. Few would argue that the result isn't "their" picture. And I seem to have a hazy memory that in France, in the very early days of hot-air balloons, cameras were sent up in the balloons, their shutters tripped by timers. Again, though, I'm not sure if the notion of the "authorship" of the results was important to anyone.

I'm sure others can think of more examples.

Here's a wrinkle: a woman in a class ahead of mine in art school took the pictures for her graduation project using infrared film but shooting in complete pitch darkness. (The subjects were scantily-clad people moving about in a dark room.) She pushed the button, but she had no idea what the camera was seeing when she shot.

A number of people seem to have had their ideas of proper authorship (or credit) challenged or offended by Doug Rickard's method. To me, the method is what makes the project interesting. It's enough merely to describe what was done. Anyone can then see plainly, for themselves, what Doug's own input was, and was not. It doesn't have to be argued any further than that.

If he were pretending that he'd made the pictures in some other way than they actually were made, then I'd have a problem with it. But if the method is transparent, then it just adds to the interest. Google Street View is a common contemporary visual experience. I sometimes "go somewhere" and poke around just for the plain old pleasure of looking and seeing—same reason I go to flickr or pick up a photo book or do a random Google image search. (I like looking at pictures; so I look at pictures a lot.)

Here's another complication. This is another idea I've had in my head for years, and for all I know it may be one that's already been done. The idea was to get a bunch of underwater cameras, load them with film (it's an old idea, pre-digital), then go to a public pool and pass them out to swimmers. Let everyone who wants to expose a roll of pictures, then reload the camera and let someone else have it. Repeat as needed (that day, different days, different pools) until there was enough to work with, then make good prints and edit the keepers into a book.

Assuming I carried out the project, would the resulting book still be "my" book? Or would it not be because I didn't actually get in the pool or press the button? Would the pictures be my pictures?

(And if someone within the sound of my voice steals that idea and actually does it—they'd have my blessing—would it be entirely their book?)

See, to me, it isn't so necessary to hash out the distinctions of authorship or ownership or credit, as long as the method, whatever it is, is clearly and honestly described. The point is looking at the pictures and whether they're good to look at; the visual results are the thing.

Mike

Coda: There is a story somewhere (I don't recall where—the great filing cabinet of my mind is getting less organized as time goes by) of Richard Avedon being stopped by some tourists, who asked him to take a picture of them using their camera. I doubt the result, wherever it is, would be truly deserving to be called "an Avedon." Avedon, for his part, mused about how much he would have had to charge the tourists for the shot, had they known who he was. —MJ[Thanks to Gary, whose comment to the previous post inspired this. Although he probably said it better than I have, and in far fewer words. —MJ]

Original contents copyright 2012 by Michael C. Johnston and/or the bylined author. All Rights Reserved. Links in this post may be to our affiliates; sales through affiliate links may benefit this site.

A book of interest today:

(To see all the comments, click on the "Comments" link below.)

Featured Comments from:

HD: "I think I posted something similar to this before, but in climbing, there are all sort of ethics and standards. A barefoot ropeless ascent with no prior knowledge is the highest standard, which few ever meet even once. But the more important standard is, say what you did. We stopped 200 feet from the summit. We had help from Sherpas. I pulled on gear.

"Just that. Say what you did.

"It works for many things.

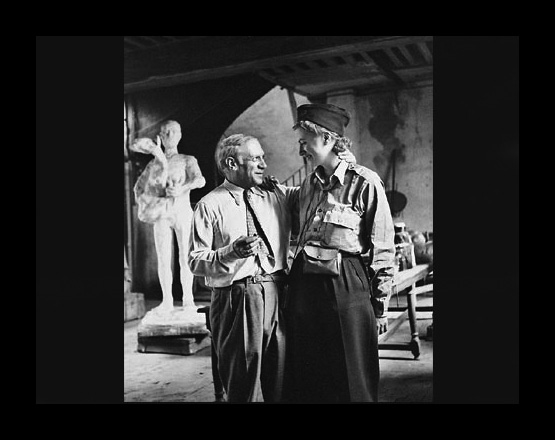

Photo by Lee Miller [sorry, HD, I couldn't resist. —Ed.]

Photo by Lee Miller [sorry, HD, I couldn't resist. —Ed.]

"Funnily enough, I was in San Francisco a couple of weekends ago. Went to Pier 24, saw the Cindy Sherman exhibition, and went to the Man Ray/Lee Miller exhibit. One of the photos was of Lee Miller meeting Picasso in Paris at the end of the war, titled 'Self Portrait of Lee Miller with Pablo Picasso, Liberation of Paris (photo taken with Lee Miller's camera by Robert Capa).' Or some such. We had a good laugh. Who took the picture? Lee Miller, because it was her composition? Or Capa, who pressed the shutter? The caption read 'Photo by Lee Miller.'"

Mike adds: About that, see also S. Chris's comment below.

James Rhem: "Mike, it almost seems to me that the two ideas in your last paragraph are, if not at odds with each other, in tension with each other. One champions the method (or knowing about the method, the concept) as primary; the other champions the final result, the artifact, the photograph. In the end I think you want to say it doesn't really matter how it got there (or it matters only a little and in different ways to different people); what matters most is the photograph itself."

Mike replies: I don't want to be polarized by argument regarding the Rickard book, before I've had a chance to make up my mind. I like a few of the JPEGs I've seen online; the idea seems interesting, as it attempts to distill a vast visual land I've visited many times (Street View), one that seems peculiarly relevant to visual life c. 2012; and I'm not bothered by the authorship questions. But I tend to decide how I feel about something by seeing it. So I'll reserve judgement on the book till I see it, and the prints till I see those. I'm open to the project, and looking forward to seeing the new book.

Omer: "I imagine stuff like this happens in the scribe universe though not being a writer myself I don't have knowledge of a specific example. But I am curious, as a writer Mike, how would you feel if the context here were changed from the craft of photography to that of writing?"

Mike replies: Glad you asked, and for my answer I'd like to refer you to Malcolm Gladwell's 2004 essay "Something Borrowed." It's an account of his confrontation with a playwright who based a character in a play on the subject of a profile he had written. She learned of the subject through his article, and she used many of his words in the play—and was subsequently widely accused of being a plagiarist, to her great distress. "Something Borrowed" is subtitled "Should a Charge of Plagiarism Ruin Your Life?", and ends with the playwright weeping in his living room.

The original New Yorker article appears online both at Gladwell.com and at the New Yorker Archives site, but either the original article was edited or Malcolm expanded it for his book, because the ending of the essay as it appears in Gladwell's collection What the Dog Saw

is more extensive.

(Oh, and you'll want to listen to the Beastie Boys' "Pass the Mic" as you read the essay, for reasons which will become obvious.)

Ed Hawco (partial comment): "Something I haven't seen much mention of in this discussion of Doug Rickard's book is the fact that his selection (or 'curation') of the images involved more than simply choosing from a set of existing images. Google Streetview represents a crude kind of 'virtual reality' in which we can immerse ourselves in a location and then move around 'physically' as well as virtually turn our heads. There are no pre-composed images in Streetview; any screenshot you take from it comes from you deciding where to 'stand' and where to 'look.'"

That is way more abstract than just choosing from a set of static images."

Bruce Robbins (partial comment): "Can I be quite frank here? What Rickard is doing is garbage. Imagine if Garry Winogrand had dumped some of his prints onto a table and said to his students, 'Help yourselves.' If one of them had scooped up an armful and made them into a book, would that have been legitimate?"

Mike replies: Well, is it legitimate that Cartier-Bresson didn't edit many (if any) of his books? He would turn an editor loose in his contact sheets and they'd select the pictures for the books.

Also, I'll assume you won't be buying either of the Vivian Maier books.... :-) She didn't even see many of her pictures, much less select or sequence them.

Dan: "Similar—but not directly related—to the idea advanced in this post, I'm a big fan of what I would call a new type of curator that's been enabled by the Internet—that is, people who cull photographs from all corners of the internet (with proper attribution, of course) purely based on the echoes shared by photographs which otherwise were created in completely disparate conditions. The two examples I have in mind are bremser.tumblr.com and mpdrolet.tumblr.com. Seems like one way to make sense of the tsunami of pictures that we've been inundated with."

Colleen: "Your underwater project reminded me of this brilliant project of Stephen Gill."

Mike replies: That's great. I would buy that book...is there one?

S. Chris (partial comment): "Funny this came up now. I was just thinking about photo authorship in the context of an upcoming photo class. It is a tradition to assign a self portrait project in the first two weeks, and because of our limited resources (no tripods, remote releases, or even timers on most of the cameras) one tacitly approved method is to have your 'self portrait' made by somebody else, often one of the other students. Sure, we coax them to set it up as carefullly as possible, etc, but they are using film (no instant review and feedback/correction), and, practically, the standard is very low. This bothers me a great deal, actually, though it seems I am the only one. To me, it seems to deeply misunderstand what goes into making a picture. I have no problem with timers, remote releases, or trip-triggers, but if another person is framing and choosing the moment...then it really isnt your photo."

Mike replies: I have an old friend who makes a handsome living writing stars' "autobiographies." In some cases she is credited on the cover ("...with Hilary Liftin"), in other cases she is not mentioned at all—and in the most extreme cases it's in her contract that she has to keep her participation a closely guarded secret. I haven't asked her how much of the actual writing she does, and I'm sure it varies, but I'll bet it varies from 80% to 100% or something close.

Maris Rusis: "Maybe it's time for a neologism. The American art critic and philosopher Arthur C. Danto has, I believe, suggested PHOTOGRAPHIST as an term to describe a person who consumes photographs as raw material for their art. A PHOTOGRAPHER, by way of difference, makes photographs as the art itself."

Mike replies: That's a great idea, and I like it, but the problem is that the root noun would be the same for both. That is, how would you fill in the blank with the following syntax: "————s by Josephine Blow"? "Photographisms"? Words get messy; old ones have been sorted out by long negotiation, but with new ones the mess is right there in a puddle on the floor....

MikeF: "Kodak used to say 'You Press the Button, We Do the Rest.' (As Ken White noted somewhere above.) Which leads me to ask 'If I don't press the button, what am I here for?'"