By Ken Tanaka

Two thousand and nine thus far has seen some interesting and exciting new developments in camera design. Leica’s S2 perhaps shines brightest for the boldness of its new sensor format. But for those of us outside the investment banking and hedge-fund-management worlds, Olympus's E-P1 digital Pen

represents a far more accessible and encouraging development. A small interchangeable-lens camera with good performance at a reasonable price: just what a big slice of the enthusiast market wants.

As it turns out, this is such an old tune that Frank Sinatra could have recorded it. So what's the root of the history that Olympus commemorates with the E-P1?

I knew nothing of the heritage of the Olympus Pen before the E-P1’s introduction. But as I nosed into the Pen’s history I found it to be a delightfully human story of ingenuity and perseverance in a culture that simultaneously celebrated and discouraged both.

The young Maitani

The year was 1956. Japan was well in its stride toward its post-war industrial swagger. The camera industry was doing well but looking to do much better as peacetime and brightening economies encouraged travel. The big Japanese optical companies, now deeply invested in camera manufacturing, were busy trying to knock off the industry’s prestige brand, Leica. Eiichi Sakurai, the head of Olympus’s camera division, became intrigued by a very clever rangefinder patent that a young student had filed. Breaking form from Japanese corporate protocol, Sakurai personally invited the student, Yoshihisa Maitani, to join Olympus in 1956 when he finished his university studies.

Maitani had loved cameras and photography since he was a boy. His family owned a Leica which he would often use on the sneak. He built his first camera when he was 10 and was fascinated by camera design.

But he never dreamed of trying to build a career from this interest. He was studying automotive engineering and, in fact, had already been offered a post-graduate position with an auto manufacturer when Sakurai approached him. But he eagerly joined Olympus where he was fast-tracked into camera design.

Maitani’s first big project was to design a small, precise, but easy-to-use consumer camera. The target price point was established as a meager 6,000 yen, roughly a third the price of Olympus’ least expensive cameras of that day. (Leicas were selling in the 200,000-yen range.) This low target price, plus Maitani’s decision to use a half-frame format to make the camera even more economically attractive to consumers, presented him with some formidable technical hurdles. But it was the organizational hurdles that proved to be far higher*. Basically Maitani had a very hard time getting anyone in Olympus to take the project seriously. A cheap half-frame camera was considered an unworthy junk project. The Olympus factory management even refused to build the cameras, forcing Maitani to outsource the Pen’s initial manufacturing.

But the smart and ambitious Maitani persevered. In October of 1959 the first Olympus Pen hit the market and became an instant bestseller in Japan. It also spawned a bit of a half-frame camera craze for the next decade and beyond.

Prototype of the original Pen, internally named the "Olympus 18" during development

Prototype of the original Pen, internally named the "Olympus 18" during development

The first Pen models were rather like squarish point-and-shoots, bearing little resemblance to the Leica-like form most commonly associated with the Pens (and which the E-P1’s design echoes). The design emphasis for these early Pens was quality, simplicity of use, and compactness. During the next nine years Olympus would introduce eleven models of these compact, fixed-lens Pen cameras to an eager worldwide market.

The Pens were a big hit with casual snappers but not as much with the burgeoning amateur enthusiast market. So in 1963 Olympus once again enlisted Maitani’s design talents, this time to create a Pen aimed at both serious amateurs as well as casual snappers; a Leica for the average Joe. This meant not only opening the Pen to interchangeable lenses but also maintaining a 35mm rangefinder-size body while using a reflex design. It also meant keeping the camera’s operation simple. These were formidable technical challenges for Maitani; fortunately, the record-breaking sales success of his first Pen designs had earned the young engineer significant stature within Olympus. He was even permitted to hire an assistant for this project! The result was the Pen F, the first and only single-lens reflex half-frame camera.**

The Pen FT with 38mm ƒ/1.8 Zuiko lens

The Pen FT with 38mm ƒ/1.8 Zuiko lens

Fast-forwarding to the 1966 Pen FT, the second and final F model**, we can see the culmination of Maitani’s design solutions. One of the main challenges in maintaining a small body was creating a through-the-lens viewfinder without the bulk of large Porro prisms to right the lens image. The solution was to create an elaborate system of tiny prisms and mirrors that compactly delivers a true image to the eyepiece. The compromise of the design was a somewhat dimmer viewfinder. This was not the big issue it would be today, since the camera could not even handle emulsion ASAs (ISOs) higher than 400. Few Pen owners were shooting in the dark.

Looking through the Pen F’s viewfinder can initially be a bit jolting. Since the camera uses a half-frame format it splits the normal 35mm frame horizontally in half. So rather than 36mm x 24mm you get an 18mm x 24mm frame oriented vertically. That is, holding the camera in a normal landscape orientation produces a portrait-oriented frame. (This actually turned out to be easy for me to get used to.)

Of course the Pen F predated the introduction of electronic exposure control by many years. But it did feature a rather clever through-the-lens (TTL) metering system. Like most metered cameras of the day, the Pen F was basically what we would now call a "shutter-priority" exposure system. You first set a ballpark shutter speed between "Bulb," which keeps the shutter open for as long as you hold the shutter button down, and 1/500th of a second. As you look through the viewfinder you see a floating photometer needle point to a number on the left. You then turn the lens’s aperture ring to index at that number to produce a "correct" or metered exposure! What could be simpler?

The Pen F's unique vertical mirror

Strip of 35mm film shot with the Pen FT

Strip of 35mm film shot with the Pen FT

Exposures

Olympus knew that getting good exposures was the primary challenge of using cameras of the day. They also knew that the average camera owner had no interest in dealing with those f-numbers. They demanded (and still demand) maximum simplicity.

But the shutterbugs love "those f-numbers."

Maitani’s solution to draw both types of customers was remarkably simple and effective. Pen F lenses featured an aperture ring that had two sets of indexes, one corresponding to the viewfinder’s simple 0-1-2-3 etc. meter indications, the other showing the actual f-stops (1.8, 2, 2.8, etc.). These indexes were engraved 180 degrees opposite each other on a floating outer ring which could be read from either the top or bottom of the lens barrel. If you were a "sophisticated" owner you could even rotate this index ring to show f-stops on top. (You would have to count stops to correspond to the meter numbers but, hey.) Problem solved!

Aperture ring indexes in the standard position

Aperture ring indexes in the advanced user position

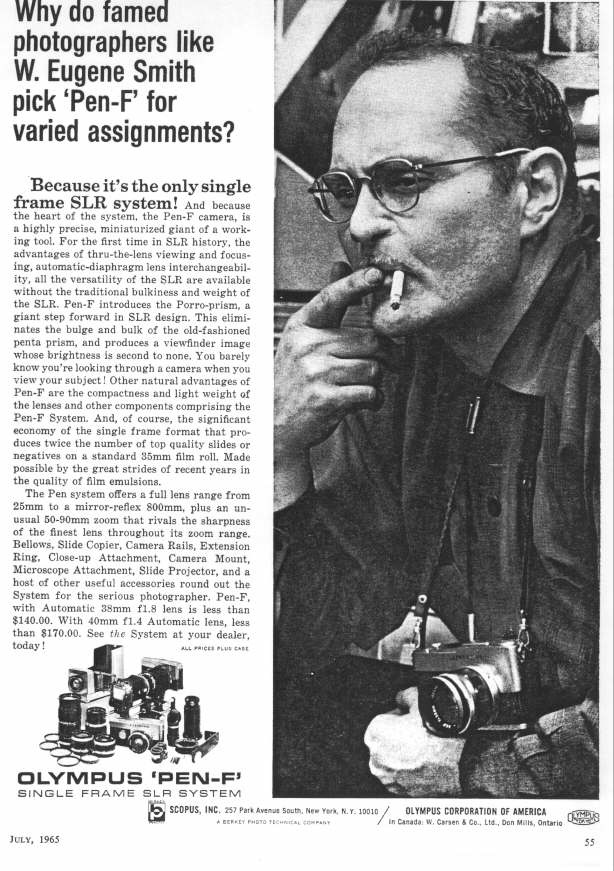

Olympus took a new marketing tack to sell the Pen F. They very much wanted a piece of that Leica trade, particularly from the U.S.. The camera had a similar size and feel to a Leica but for a price of $140–$170 it was a much cheaper thrill. They enlisted photojournalist Eugene Smith to endorse the Pen F, giving it a certain "Marlboro Man" panache. (Can you imagine such an ad these days?!) Instead of calling the Pen F a "half-frame" camera, which sounded wimpy and discounted, Olympus called it a "single-frame" camera. Isn’t advertising fascinating?

It worked. Although they were nearly forgotten today, Olympus’ Pen cameras became one of the most successful lines of cameras in history, selling over 17 million units in just over ten years.

Maitani after the Pen

Following his work on the Pen Yoshihisa Maitani designed many other Olympus cameras such as the iconic OM-1, the OM-4, and the XA. Maitani actually became a celebrity for Olympus after being featured in a famous series of ads, something quite rare within the whack-a-mole conformity of 20th century Japanese business. (He even has a fan site!) Maitani retired as a managing director of Olympus in 1996 following an extremely successful 40-year career.

Sadly, Maitani passed away this past July at the age of 76. I hope he was able to see the digital incarnation of his Pen. Warts and all, I think it would have made him smile.

Ken

P.S. I did not receive any form of compensation or cooperation from Olympus for writing this article. I researched it myself and I own all of the equipment used and/or illustrated.

Related References:

The World of the Pen

YouTube Pen Channel

*Yoshihisa Maitani’s account of the Pen’s development is a fascinating story of problem-solving and of mid-20th century Japanese industrial culture. You can read his first-hand account in this English translation of a speech he delivered in 2005.

**See Hugh Crawford's and Dwig's comments in the Comments section.

Featured Comment by Skip Williams: "If anyone is looking for more detailed information on the history of the system, I have 14 scanned vintage advertising and editorial pieces on my site. There are a few more that I have, but have not had a chance to scan."