By Eamon Hickey

I said in an earlier post that Live View is a no-brainer and promised to expand on that theme a bit. Live View is not new at all, of course—video cameras and digital point-and-shoots have had it for years—but it has been greeted with a lot of scorn by many SLR users. That scorn notwithstanding, this is an oncoming tidal wave. The potential economic and photographic benefits of it are just too compelling, a fact clearly on the minds of the camera companies who have stuck Live View into most of the DSLRs introduced in the past 12–18 months, from entry-level to top pro model. I also think it's a tremendously interesting development, since the way a camera lets the photographer view the scene is arguably its most fundamental quality. I'm in agreement with those who think it's likely that forms of Live View, whether using LCDs or electronic viewfinders (or wireless iPods or whatever), will eventually be the dominant viewing mechanism at nearly all levels of photography.

Future wonders aside, the current form of Live View in most DSLRs is only sporadically useful, and the E-3 is not really an exception. As with nearly all current DSLRs that have the feature, the E-3 enables Live View by flipping the camera's mirror up and using the main sensor to feed a video image to the LCD, which necessitates a weird, and slow, mirror dance (for autofocus and metering) whenever you make an exposure. A significant shutter delay and LCD blackout results. The system works perfectly okay for static subjects, and for some things—notably macro photography of non-moving subjects, especially close to the ground—it can work a lot better than the regular optical viewfinder. You can quibble about the specific implementation of the E-3's Live View mode—the way you navigate the various displays and certain operating characteristics—but, overall, it works roughly as well as other versions of this form of Live View. And the camera's articulated LCD maximizes the number of positions and angles from which you can compose a picture in Live View mode, a definite plus (although at the cost of some added bulk for the LCD's mount and swivel joint).

I did some macro and still-life tests and was not surprised at all to find that the E-3's Live View works quite well for that kind of thing. It isn't necessary for such pictures, but it's helpful and therefore desirable. I also found it useful several times for general picture-taking—to angle the camera up against a wall at knee level for the shot of the wayward box that led off these posts, for example, or extended two feet out over the Hudson River to get a better angle on a paddleboat. These made somewhat better pictures than I could have taken if limited to the optical viewfinder. To me, in short, Live View is an obvious win, enabling some shots that weren't possible before and making others easier and more pleasant to accomplish, all at minor cost.

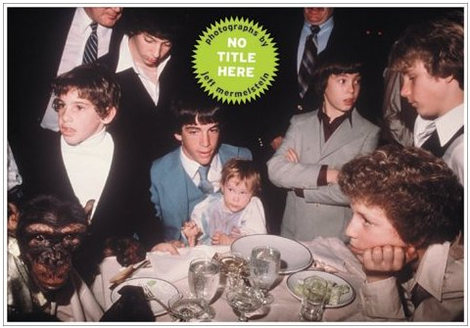

I also decided to see how far I could push the E-3's Live View, despite the shooting delays that are inherent to its form of the feature. One vague desire I've had kicking around in my head for awhile is to try to photograph, in some interesting way, the dogs of New York. While not as famous as their Parisian kin, New York's pooches are really a fascinating cohort—ubiquitous, wildly multifarious, winsome, jaunty, often hilarious. It occurred to me that Live View would make it easy to shoot ground-level full-face portraits of all sorts of dogs, big and small, as they made their way about the city. That, in turn, evolved into the idea that it might be fun to make and print digital contact sheets of the faces of every dog that passed a particular spot over a given time. The "contact sheet" you see here, a preliminary test of the notion, is a selection of the dogs that walked down a particular path near The Great Lawn in Central Park from 6-7pm one Thursday evening.

To shoot them, I sat cross-legged on the ground at the side of the path, with the E-3 and the 50–200mm SWD resting on a small belt pack in front of me. After I learned to continue panning correctly even when the LCD was blacked out during the mirror dance, my hit rate (i.e. shots in focus) was about 40–50%—better than I expected given that this form of Live View shouldn't really work well for shooting moving objects. Perhaps I should clarify that my hit rate was less than 50% with the smaller, quicker, younger dogs, and maybe a bit better than 50% with the larger, more temporally seasoned hounds. (You can see on my contact sheet that some of the shots are very crisp and others just a tad soft—the really out-of-focus ones were trashed.) Could I have lain prone on that path for an hour, eye to an optical viewfinder, without weirding people out? Maybe, but I wouldn't have. Life's too short. So I'm actually modestly bullish on the E-3's Live View for more than just static subjects. I don't think these dog portraits have turned out as charming as they were in my mind's eye, but if I decide to keep trying I'd be willing to spend some more time shooting this way with the E-3's Live View.

The project would go much better, however, if the E-3 had a second Live View mode that Olympus offered with the now-discontinued E-330. In addition to the mirror-up/main sensor Live View mode of the E-3, the E-330 could do Live View with the mirror down, using a secondary sensor in the viewfinder to feed the video image to the LCD. This was called "Mode A" on the E-330, and it allows the camera to work essentially as normal, eliminating the mirror dance and the delays that go along with it. The current Sony A300 and A350 use a similar concept. It's much better for shooting the general run of everyday life (like Live View in a point-and-shoot but with the other benefits of an SLR). I borrowed an E-330 from Olympus two winters ago to give DSLR Live View an extensive play. I used Mode A for both the shot of the crowd and flags at Rockefeller center, where I held the camera as high as I could reach, and the ice skating shot (done with the wonderful Olympus ZD 7–14mm ƒ/4 lens), where I panned with the skaters, holding the camera at waist level just on the inside edge of the fence at the skating rink in Bryant Park. I strongly hope that Olympus revives Mode A in one camera or another. (And good for Sony for their version of it.)

The secondary sensor method of Live View, at least as done by Olympus and Sony, does have some drawbacks, however, most notably smaller or dimmer optical viewfinders. To really make Live View work well in cameras with DSLR-level speed and performance, the camera companies will have to make main-sensor Live View work much better, with major improvements in the forms of autofocus and metering that work using the primary imaging sensor. But I have no doubt they are furiously developing such improvements right now. This is too important a technology for it to be otherwise. If I'm still taking pictures in fifteen years, I'm expecting to be happily rid of the complexity, expense, and especially the bulk of mirror/pentaprism assemblies and composing freely from multiple angles with a Live View LCD or electronic viewfinder. Today, in its current somewhat kludgy form, I'd rate Live View modestly desirable (especially with an articulated, or at least tilting, LCD)—a feature I'll look for but not yet a must-have.

______________________

Eamon

______________________

Olympus E-3 at Amazon U.S.

Olympus E-3 at B&H Photo

______________________

Olympus E-3 Review Part 1 (preface)

Olympus E-3 Review Part 2 (first impressions)

Olympus E-3 Review Part 3 (lenses and autofocus)

Olympus E-3 Review Part 4 (live view)

Olympus E-3 Review Part 5 (miscellanea)

Olympus E-3 Review Part 6 (conclusion)