Photography: Generic name for mechanical image production using light as an agent.

Photograph: A product of photography, usually, but not always, a physical object or a printed or published picture.

Traditional Photography: Photography using optical/chemical means, usually film- or emulsion-based, including all the technologies that predated digital imaging.

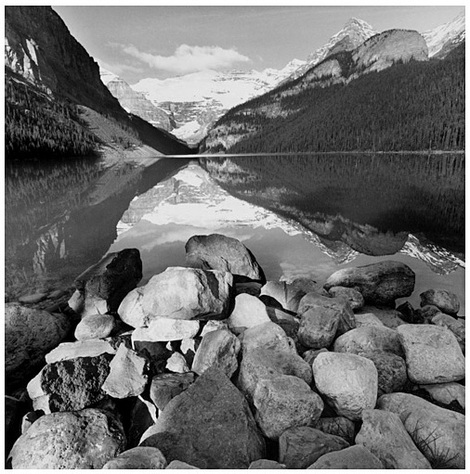

"Straight" Photography: A term coined in the 1930s by members of Group ƒ/64 and others referring to photographic pictures that respect the lens image (except as regards color, if only because for a long time color photography was impracticable). Now potentially applicable regardless of the recording medium.

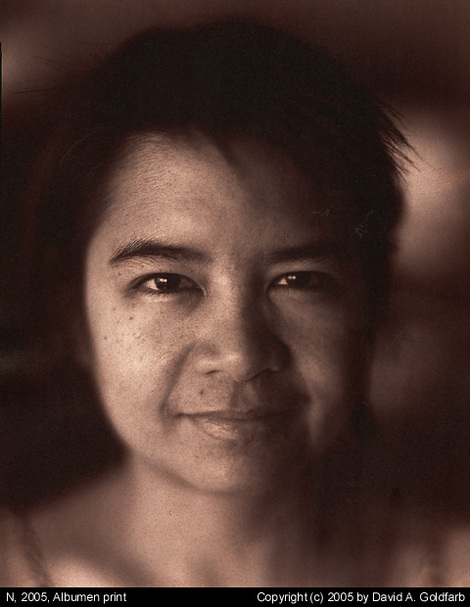

[Photographic] Print: A photographic picture reified on a substrate, usually paper.

Digital Imaging: Generic term for pictures recorded on sensors or that can be stored as computer files.

Digital Photography: Photography using digital cameras.

Digital Image: A picture in digital form, usually but not always originating from a sensor capture or scan.

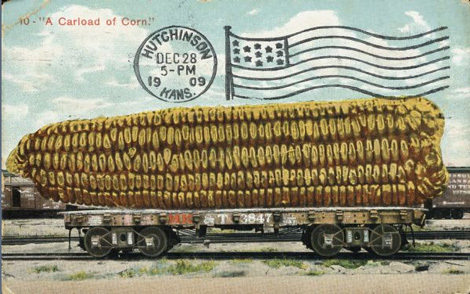

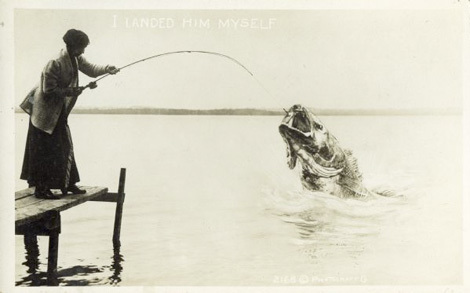

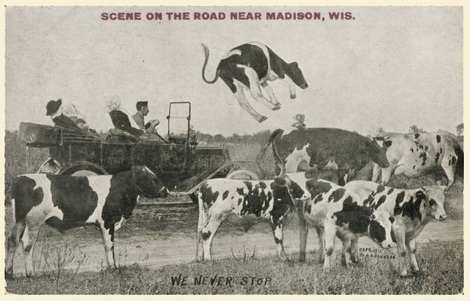

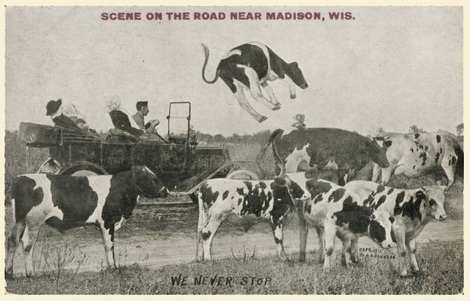

Photo-illustration: Manipulated or modified pictorial images derived from photographic [digital or analog] originals.

Digital Illustration: Umbrella term referring to manipulated or modified images that include elements that are not photographic in origin, or that rely heavily on software.

-

Terminology doesn't define

It doesn't take a great deal of reflection to deduce that there are among these terms both overlap and ambiguity. But that's okay, because terminology doesn't define—it describes.

For one thing, in many situations the photographic aspect of a photographic representation is meant to be transparent: thus, a photograph of a painting reproduced in a book about art might be referred to as a "painting," or a digitized representation of a film negative is referred to as a "negative" even though the first is a photograph and the second is a digital image.

A 4x5" film negative. See how that works?

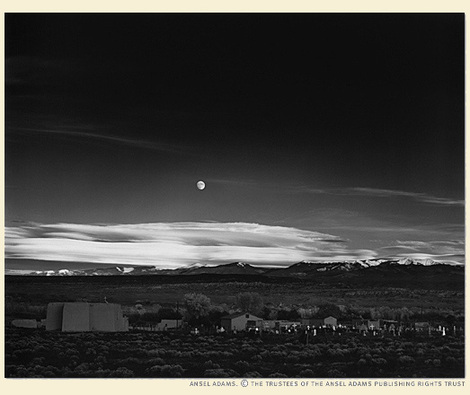

The most annoying problems might arise when a work in one category has slight aspects of another. Ansel practiced "straight" photography (of a stentorian and virtuosic character, but straight still), but in one case he photographed a landscape in which some numbers had been spelled out on a mountainside (the year of a graduating class, if memory serves) in white-painted rocks, and he retouched this feature out of his picture. This is prehistoric potatochopping, to be sure, but does it make the picture a photo-illustration? Not really. It just crosses that boundary. (Unless you want to argue that all of Adams's unpeopled, pristine wilderness is essentially a distortion, but that's another discussion.) And obviously, digital images that look exactly like straight photographs, but aren't, are a special case; they seem to add to our store of visual facts but they're fiction. (Novels, in English-language publishing at least, almost always have the word "novel" on the cover.)

Not a photograph

Photo-illustration and digital illustration are essentially synonyms, but, hopefully, enough distinction will eventually emerge to make the difference useful. (For a good example of a guy who's very good at photo-illustration, in his case of the commercial variety, check this link.)

There's a term I personally detest, and that's "digital photograph." No such thing. Either be brave and call it a photograph, or be precise and call it a digital image, I say. However, I don't get to say.

Incidentally, my own interest and allegiance is mainly to straight photography. If a picture doesn't respect the medium's potential connection to the real world, why not go be a watercolorist?

I was powerfully tempted to add one more term:

"Expressive" Photographs: Pictures exploiting peculiarities of photographic materials and equipment, optical peculiarities of lenses, or modes of capture.

...But I sense that that's just me talking to myself, inventing distinctions I wish pertained; I don't think that one relates to either common or easily-intuited usage. The rest of the definitions above are reasonably widespread and well accepted.

_____________________

Mike

Featured Comment [excerpt] by John Camp: "One of the old guarantees of cameras was that in some sense, the 'scene' was out there—not only in the artist's mind. If you can't get a straight shot of it, for some reason, then (in straight photography) it didn't exist. I've mentioned somewhere else the L.A. Times faked photo of an American soldier in Iraq who seemed to be menacing an Iraqi and his small child. The scene was composited of two photographs taken at about the same time, but the composited photo presented a radically different view of the situation than the straight photos, and might have had a powerful political effect if the fakery hadn't been detected. So that's the problem—if a scene doesn't exist, but has to be composited, then it didn't exist—and to present it as if it did, as a straight photo, is a form of lying.

"Artists compose artificial scenes, and in fact somewhere in the U.S. right now there is an art show of 'multiples,' which are variations on a scene which slightly change the arrangements of people, horses, etc. (The ones I saw in a review were by Degas, at a race track.) But paintings, by their nature, advertise their artificiality—nobody believes that the horses and the jockeys stood absolutely still and posed for the eight or ten hours—or six or eight months—it took to do the painting. Manipulated photos, presented as straight, don't have this built-in check. So you get National Geographic moving pyramids to get a better (but impossible) view, etc. People argue that Adams manipulated photos with filters, with dodging and burning, etc., and he did, but what he was doing was changing the conditions of the machine (with filters) or the light (with dodging) but usually he was not attempting to change the conditions of the scene itself (though he apparently did in the example cited by Mike.) IMHO, that photograph is also a lie.

"The problem is not so much with the image itself, as the presentation of the image. If you present it as straight, and it isn't, then you're not telling the truth."

Featured Comment by Gordon Lewis: "It seems to me that many lovers of digital photo manipulation want the advantages of verisimilitude (i.e. 'it looks real') without being restricted to reality itself. But they can't have it both ways: Once viewers begin to doubt whether what they see is a close representation of what was happening in front of the camera at the moment of exposure, then the game is over. The crowd no longer believes in magic. They can only be impressed by how good a performer you are. Ironically, in such an environment, reality becomes that much harder to accept. The audience won't believe you even when you're telling the truth (or as close to it as you can get). The credulous will still gasp in wonder, but many viewers will offer little more than a cynical yawn."